What makes a great regional museum? This question needled me after a recent, fantastically rewarding visit to the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, NY to see “Five and Forward,” the latest installation of works from the museum’s permanent collection. The one-word answer is “depth.”

As the superbly curated installation of works spanning the historical range of the museum demonstrates, the depth of a permanent collection offers an automatic advantage to any museum’s exhibition program. In addition, the depth of experience at the Parrish among curators and decision-makers and the institution’s relationships to the East End’s art and educational community provide the kind of foundation that is a fundamental requirement for a top-tier museum.

The historical dimension of the “Five and Forward” installation is irresistibly lovely, keyed to that sweet spot of American Impressionism so deftly relayed to the canvas in such gems now on view as seven paintings by William Merritt Chase, who founded his plein air art school in Southampton in 1891. With so many of his works held in the collection, Chase is “family” at the Parrish, which yields an intimacy to the museum’s presentation of a group of studio interiors and portraits together with the brilliant curatorial touch of a pair of cyanotypes of the artist at home.

Chase’s school was the breakthrough moment for the East End as a destination for artists and their students, putting the Shinnecock dunes and endless beaches on a par with the Hudson River school’s expansive vistas. With so many choices, the editing of the Chase gallery at the Parrish is a pleasant challenge, and the achievement of this installation is its juxtaposition of the atmospheric interiors and a sun-drenched, more typical landscape. The latter work is small but replete with the multi-hued radiance of the Monet and Renoir palette, chasing the sun flares across Southampton.

The centerpiece is an important landscape, The Big Bayberry Bush (The Bayberry Bush) ca. 1895, which returns to the museum after being on an international tour. With 40 canvases by Chase for Alicia Longwell, the chief curator, to choose from, visitors to the museum could not have asked for a more important piece.

.

"The Big Bayberry Bush (The Bayberry Bush)" by William Merritt Chase, ca. 1895. Oil on canvas, 25 1/2 x 33 1/8 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y., Littlejohn Collection.

.

Some of the same institutional wealth of variety and quality is found in the Modernist rooms, where Fairfield Porter holds sway with his large and inviting landscape Lunch Under the Elm Tree (1954), as gracious a plein air picnic as any. In a sunny gallery, Dorothea Rockburne’s Capernum Gate (1984) grabs the light along the grains of its gold leaf and elevates its geometry to the level of pure energy. In the same room, Theodore Stamos’s hearty After Edna (1954) taps the sources of the region’s renowned Abstract Expressionist heyday.

A pair of galleries dedicated to two stars of that generation, Alan Shields and James Brooks, offered the kind of visual dialogue that is often lost in a group show. I shuttled between the large, color-filled works of Shields and the powerful paintings of Brooks, whose palette had a commensurate chromatic punch.

.

Installation view of the exhibition "James Brooks (1906–1992)," part of the Parrish Art Museum 2018 Permanent Collection installation, on view November 10, 2017 to October 28, 2018.

.

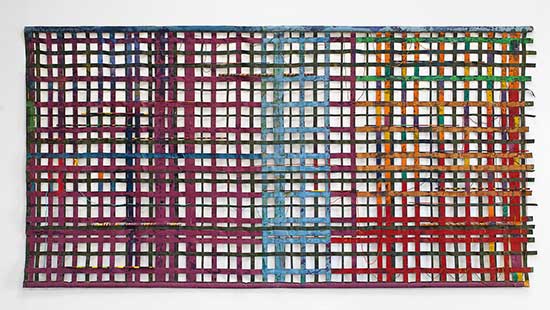

Installation view of the exhibition "Alan Shields: Common Threads," part of the Parrish Art Museum 2018 Permanent Collection installation, on view November 10, 2017 to October 28, 2018.

.

Shields is a tectonic artist, in the sense that architectural historian Kenneth Frampton used the term to describe the weaving of vertical and horizontal elements in design. The literal weaving of belts and threads, with the individual voices of color passing over and under one another, makes the huge work Devil, Devil, Love (1970) one of the most absorbing experiences in the building. It can be appreciated from both front and back, which is a crucial aspect of the work in the show, as with Dorothy Jean (1973), a double-sided assembled screenprint in Frank Stella-worthy reds and golds.

.

"Devil, Devil, Love" by Alan Sheilds, 1970. Cotton, belting, acrylic, thread, beads, and wood, 96 x 194 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y., Museum Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Robert F. Carney Fund.

.

Shields challenges the viewer to move around his work as one does a sculpture, and color always stimulates my tendency to guess the theoretical underpinnings of the use of a spectrum. For the sheer audacity of its red, I also enjoyed the Gorky-esque Chinese Still Life (1947) of Brooks, while his huge gestural paintings like Juke (1962-70) are the heavyweights, punching those reds with force. For a lighter sensibility, I recommend Ypsila (1964), Brooks’s calligraphic antidote to loaded surfaces.

Moving on, I was unnecessarily braced for controversy as I approached the one-room special installation of 14 works curated by the artist Rashid Johnson, whose own work hews closely to debates about the painfully ineradicable racial division in the country. I was relieved to find a gorgeous selection and wonderful installation of painterly treasures, including a top-tier Hans Hofmann titled Image in Green (1950), a densely packed painting from his greatest period. The Hofmann pushed and pulled vividly across the room from the silvery whisper of Rain (Study) by Agnes Martin, an exhaling and inhaling grey and white hung not far from a phenomenally inventive wood collage on paper, Series of Unknown Cosmos x 11 by Louise Nevelson.

.

"Image in Green" by Hans Hofmann, 1950. Oil on canvas, 30 x 24 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York, Gift of Karen LaGatta.

.

"Rain (Study)" by Agnes Martin, 1958. Oil on canvas, 25 x 25 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y., Gift Robert Elkon.

.

For the curatorial commission, Johnson had been invited to pick and choose among the treasures in the state-of-the-art storage space that is at the eastern end of the seemingly endless Herzog and de Meuron building. Metal racks of paintings and drawings roll from its wings into the light. It is stunning repository of 2,600 works of art that Samuel Longstreth Parrish started collecting in the 1880s and is refreshed continually by new acquisitions.

My work as a reviewer concluded, I was fortunate enough to wrap up my visit to the Parrish in the storage area, wearing my other hat as the director of the Nassau County Museum since September 2017. Graciously attended by the Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Chief Curator Alicia Longwell and the museum’s Registrar Chris MacNamara, I was there in hopes of borrowing paintings and drawings for an upcoming show at the Nassau County Museum.

By the end of the afternoon I was not only grateful for the loan of artworks but also deeply envious of the museum’s holdings and the talented people under Director Terrie Sultan who are its stewards. A group of exhibitions as strong as the “Five and Forward” permanent collection show is just one measure of the quality and depth represented by the Parrish Art Museum.

_____________________________

BASIC FACTS: “The Permanent Collection: Five and Forward” is on view November 10, 2017 to October 31, 2018 at the Parrish Art Museum, 279 Montauk Highway, Water Mill, NY 11976. www.parrishart.org

______________________________

Copyright 2018 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.

did any other pbs viewer find it amusing that the two galleries side by side were for shields and brooks?