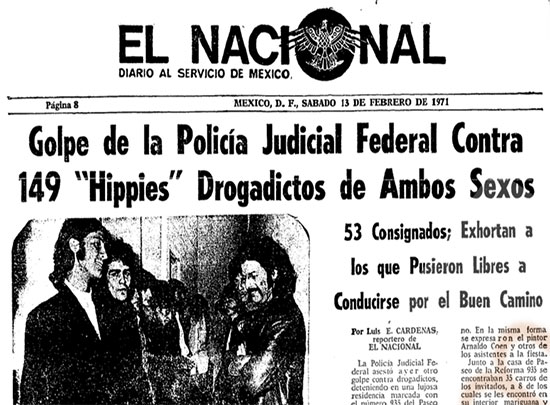

In 1971, budding artist Arturo Vega was arrested in Mexico City with 149 others. The big, boldface headline in the Mexican daily El Nacional on February 13, 1971 read: “Federal Judicial Police Arrest 149 Drug Addicted Hippies of Both Sexes.”

.

El Nacional header.

.

Vega (1947–2013) carried this clipping around with him until his death in 2013, a stark reminder of the oppression he narrowly escaped when he emigrated to New York City. The detained “hippies” were actually 148 important actors, actresses, artists, writers, poets and filmmakers of the day, including the famous Chilean filmmaker Alejandro Jodorsky. They were all arrested at a party in an affluent suburb of Mexico City.

The clipping would become more than a reminder of his “hippie” past. While he initially moved to New York not long after the arrest to pursue a career in the performing arts, auditioning for the touring version of the Broadway musical ‘Hair,” he had been actively producing collages as a visual artist starting in 1970.

In his visual arts work, Vega used that headline clip as a springboard for exploring his fascination with the power of the printed word in hundreds of paintings and prints throughout his prolific career as a graphic designer and artist. Today, he is best known for his association with—and designing the round logo for—the Ramones, who are currently the subject of a retrospective called “Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk” at the Queens Museum running through July 31, 2016.

Soon after arriving in New York City in 1973, Vega took a large loft space at 6 East 2nd Street to live in and use as a studio. He started painting works based on grocery store signs but changed direction after meeting musician Jeffrey Ross Hyman (soon to be better known as Joey Ramone), before the Ramones formed in 1974 and started playing at CBGBs, located around the corner from Vega's loft.

I met Arturo at CBGBs in 1977 and was invited to his loft around the corner for the nightly after party. The loft was like a version of Warhol’s Factory loosely organized around the Punk subset of the avant-garde, with art covering the walls, well-worn couches and beds, and work tables strewn about the airy space.

Over the next few years I would help Arturo with his art career, setting up shows with him, archiving photos and memorabilia for the band, and making endless rounds of art openings in the East Village and Soho. As the Ramones’ fortunes grew, he started collecting art—Warhol, Barbara Kruger, Richard Hambleton—and he backed the short-lived gallery, Spiritual America, I co-founded with Richard Prince in 1983.

Just about every time I went to the loft, he gave me a couple of Ramones t-shirts, and by the 1990s I had more than 50 of them. For the exhibition at the Queens Museum, I have loaned three of the shirts and a rare canvas handbag he designed for a Japanese company.

At the beginning of his association with the band, Vega was knocked out by the power of the Ramones' high energy, three-minute songs and what he considered their all-American look of ripped jeans, sneakers and leather jackets, and he let them start living and rehearsing at his loft. To make them stand out, he designed a banner for the stage backdrop that simply read RAMONES in big black letters on a white background, which he hung in the loft while they practiced. The font and typography were lifted directly from the headline of El Nacional.

.

The band in front of the first banner.

.

“My house became ‘The Ramones Loft.’ It was warehouse and headquarters, often used for interviews and photo shoots,” Vega noted on the now defunct RAMONESWORLD website he created for the band. Referencing an early photo of the band, Vega explained: “In the background you can see the first backdrop I hand-painted on the occasion of a show with the Heartbreakers. We thought they were real competition so I felt I had to do something extra for that show.”

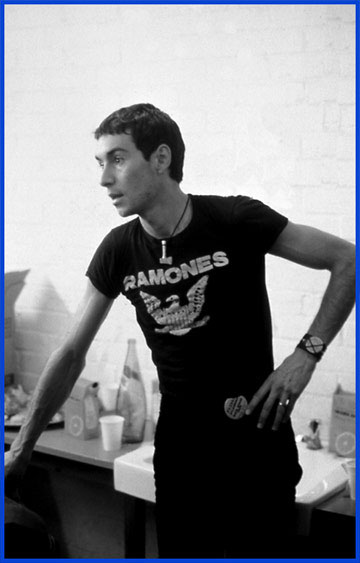

From there, Vega printed the simple new one-word logo on t-shirts to sell on the road to help pay his way to accompany the band so he could run the lights for their shows. Band members initially snickered at the idea, wondering if anyone would bother to buy a shirt with the name of an unknown band on it. In a video interview Vega claims he printed about three dozen shirts and they all sold.

.

Arturo with Joey and Dee Dee Ramone in the simple word shirt.

.

.

The band took off and the Ramones were signed to a deal within a year. Bigger shows were booked, and Vega, who was constantly on the lookout for words and symbols for inspiration, began pulling from some unlikely sources.

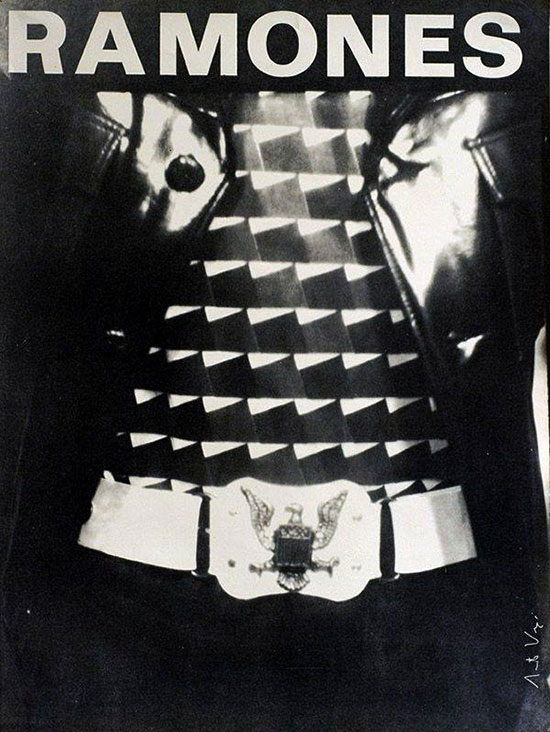

He found a cool looking eagle on a belt buckle and took pictures of himself wearing it in a photo booth in Times Square. He used the eagle under the band’s name for the logo in the next version of the t-shirt in 1976.

.

Ramones photo by Arturo Vega.

.

Vega in early shirt with logo and eagle.

.

But the logo needed more.

“I saw them as the ultimate all-American band,” he told Jim Bessman, author of the book “Ramones: An American Band.” "To me, they reflected the American character in general, an almost childish innocent aggression. I thought, ‘The Great Seal of the President of the United States’ would be perfect for the Ramones, with the eagle holding arrows to symbolize strength and the aggression that would be used against whoever dares to attack us, and an olive branch, offered to those who want to be friendly. But we decided to change it a little bit. Instead of the olive branch, we had an apple tree branch, since the Ramones were American as apple pie. And since Johnny was such a baseball fanatic, we had the eagle hold a baseball bat instead of the arrows.”

.

Presidential seal.

.

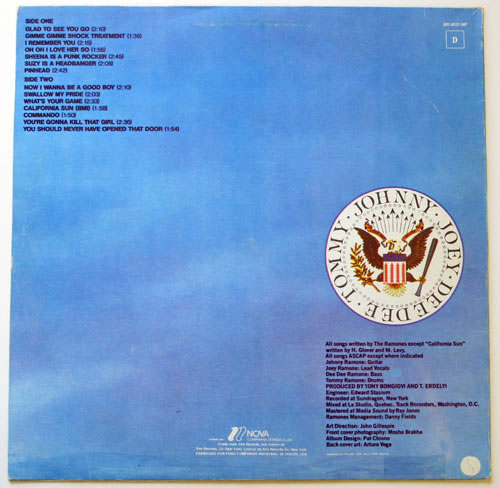

“This is the way the original logo looked on the back cover of the second album, ‘Leave Home.’ Yes, it’s before computers, and there was a lot of real cut-and-paste.”

.

The first official logo.

.

Logo on the Ramones "Leave Home" album back cover.

.

Going back to the newspaper clip, the development of the Ramones logo reflects a direct connection to the eagle in the circle of the letter O that was used at one time for the El Nacional front page logo.

Developing the Ramones logo further, a pattern of red arrows was added to the body of the eagle. Taken from a Polish-made nylon shirt Vega bought in a store on 14th Street called Robbins, the shirt was made in a few different patterns; Vega bought all of them. He wore some, taking pictures of himself wearing them with an eagle belt buckle, and kept others in original packaging—one of which now resides in a glass case in the permanent Ramones Museum in Berlin, Germany.

.

.

Vega replaced the words “Seal of the President of the United States” on the t-shirt with the names of the band members. In early versions of the logo, the words LOOK OUT BELOW replaced E PLURIBUS UNUM on the ribbon streaming from the eagle’s mouth. In later versions the words were changed to HEY HO LET’S GO in a nod to the chorus of one of the band's most popular songs.

“As much as anything, it was Arturo's very decision to make a logo for a rock group that is important,” Queens Museum curator Marc Miller wrote in an email to Hamptons Art Hub. “The only real precedent was the ‘tongue and lips’ logo that John Pasche created for the Rolling Stones in 1971. Pasche was working with a world-famous group and his logo was designed primarily to reinforce the Stones bad boy image. Over the years it has been used only intermittently because frequently the connotations it evoked did not conform to the Stones evolving identity.”

“Arturo's challenge was different since he was working with an unknown group,” Miller wrote in the email. “His logo based in the presidential seal sought to confer stature and authority and has become inseparable from the Ramones. This can be attributed to the strength of the design and to the fact that stature and authority are always desirable attributes. Its success is also rooted in the inspired way Arturo has been able to exploit the design's flexibility, adjusting it to reflect Ramones personnel changes as well as the group's new projects.”

After the logo was designed for the t-shirt, the next step was to take it to the stage, wrote Vega on the band's defunct website. “Here I am working on the second eagle stage backdrop, the ‘white one.’ It was painted right on the floor.”

.

Arturo Vega painting logo banner for Ramones.

.

Vega painting banner, 1970s.

.

Vega painting banner, 1970s.

.

Over the years the design would morph as band members came and went and different events were staged.

The shirt reinforced the branding of the band and became a real phenomenon, selling at an enormous rate. At first Vega printed them in his loft, buying the black shirts in bulk on Canal Street and setting up a printing shop in the loft. He hired local neighborhood kids to help.

I remember going to the loft in the 1980s and seeing hundreds of freshly printed shirts hanging from the overhead pipes, the overwhelming smell of silkscreen ink in the air. Music was always playing, beers were consumed and the print-a-thon went on for days.

Eventually the demand was too great, and Vega began licensing the production of the shirts to other companies. Soon that deal grew into something much larger as he made licensing deals around the world for everything from sneakers and socks, to shorts, jackets, wallets, skate boards, baby clothes, hats and stickers—all bearing the logo. They were, and still are, sold in stores globally and online.

At a show I attended in Miami Beach in the late ’80s at the Cameo Theater, I watched Vega—who had been dubbed the band’s “artistic director”— running the light board he designed, then running to the merchandise table to sell shirts. He left the venue with a large duffel bag. Later I saw it was stuffed with money, thousands of dollars in small bills, proceeds from the show. At venues in South America the band played to crowds of 60,000 and more, Vega said that every kid that went bought a $25 shirt. You do the math.

“They sold more T-shirts than records,” said Danny Fields, the band’s early manager in an interview with the New York Times, “and probably they sold more T-shirts than tickets.”

Vega had a large-scale logo tattooed on his back a few years before he died.

.

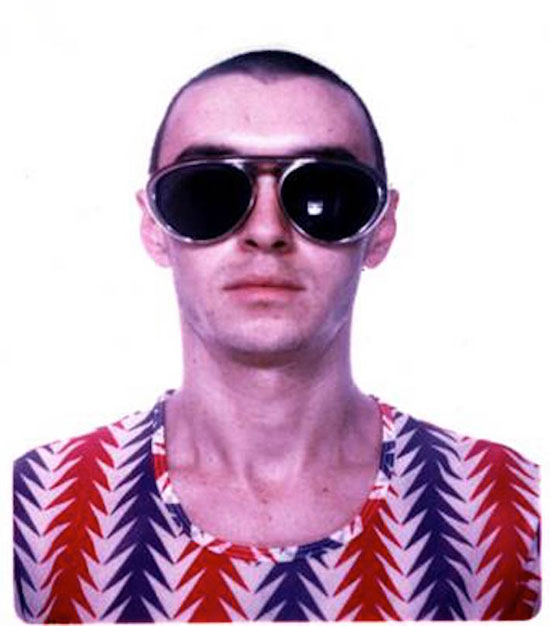

Arturo Vega. Photo by Curt Hoppe.

.

Arturo Vega poses with a banner at the loft. Photo by Keith Green.

.

Today the shirt can be seen on someone almost everywhere you go. There have been countless imitations by other bands. The exhibition at the Queens Museum, “Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk”, has many variations of the shirt as designed by Vega, including three examples on loan from my collection of about 50. Taken as a whole, the exhibition is a powerful testament to the enduring appeal of Vega’s brilliant, bold design.

.

Ramones shirts.

.

In a bizarre coincidence, at the opening of the Queens exhibit attended by thousands on April 10, 2016, a fan named Christina Gemora wore the arrow shirt. This thrift shop find was the same shirt that inspired elements of the logo 40 years ago. She had no clue about its importance. I couldn’t resist a photo-op of her in front of the banner.

“Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk” was organized by the Queens Museum and GRAMMY Museum in collaboration with Ramones Productions Inc., JAM Inc., and Silent Partner. The exhibit is co-curated by Queens Museum guest curator Marc H. Miller and Bob Santelli, executive director of the GRAMMY Museum.

.

Fan at Queens Museum in arrow shirt. Photo by Sandra Hale Schulman.

.

______________________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk” is on view at the Queens Museum, Flushing Meadows Corona Park, Queens, NY from April 10 through July 31, 2016. The exhibition then travels to the GRAMMY Museum in Los Angeles where it will be exhibited September 16, 2016 to March 2017.

Programming at the Queens Museum includes two conversations presented on June 19, 2016, from 1 to 4:30 p.m., in connection with the Ramones exhibition.

At 1 p.m., “Punk Magazine: The Original Fanzine” will feature Punk co-founder and cartoonist John Holmstrom talking with Roberta Bayley, Punk’s principal photographer and photo editor.

At 3 p.m., “The Legacy of Arturo Vega, Art Director of the Ramones” will feature artist Ted Riederer and author and filmmaker Sandra Hale Schulman. Schulman is a regular contributor to Hamptons Art Hub.

_______________________________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.

Learn all about the Ramones in the book;

“ON THE ROAD WITH THE RAMONES”.

Throughout the remarkable twenty-two-year career of the Ramones the seminal punk rock band, Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Famers, Grammy & MTV’s Lifetime Achievement Award winners and inductees into The Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry, Monte A. Melnick saw it all. He was the band’s tour manager from their 1974 CBGB debut to their final show in 1996. Full of insider perspectives and exclusive interviews and packed with over 250 personal color photos and images; this is a must-have for all fans of the Ramones.