Betty Parsons Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

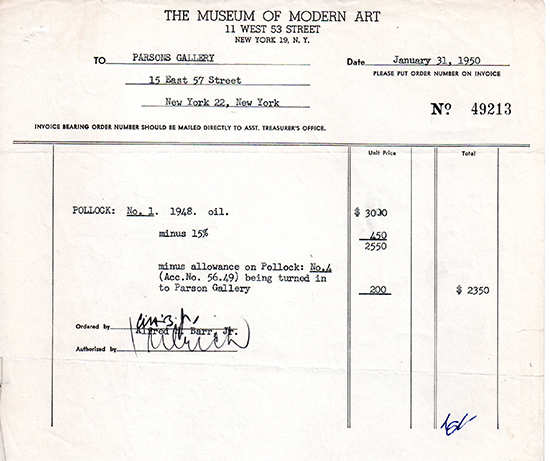

On January 31, 1950, three days after Jackson Pollock turned 38, the Museum of Modern Art gave him a belated birthday present. It was a purchase order to the Betty Parsons Gallery for a painting, identified as No. 1. 1948. The asking price was $3,000, but there was the customary 15 percent discount and a credit of $200 for another Pollock painting, No. 4, a 1948 oil on paper that was returned to Parsons.

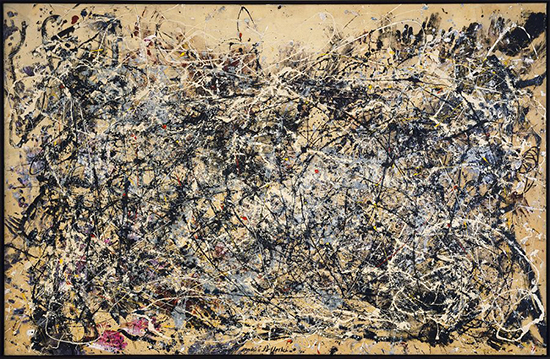

After Parsons deducted her 33 percent dealer’s commission, Pollock took home $1,566—a tidy sum when the average annual family income was $3,300. Half a year’s wages for one canvas? Pretty good. And it’s less than 6 feet tall and only 8 ½ feet wide. Not tiny, but not huge either. Hanging where it is now, adjacent to One: Number 31, 1950, in MoMA’s current exhibition, "Jackson Pollock: A Collection Survey, 1934-1954," it looks almost intimate in comparison to its younger but much larger sibling.

.

Jackson Pollock, "One: Number 31, 1950," Enamel on canvas, 105 7/8 x 209 ½ inches. Gift of Sidney Janis, 1968. All works by Jackson Pollock © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

Now known as Number 1A, 1948, it is one of Pollock’s most famous, and most autographic, paintings. In addition to signing his name at the bottom center of the canvas, he stamped it with many prints of both hands all around the perimeter, most visibly along the top edge, but also on the left side and bottom edge. There are handprints, and even bare footprints, in other Pollock paintings—notably Lavender Mist: Number 1, 1950 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC) and Number 7, 1952 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)—but none is so vividly marked by the artist’s presence.

.

Jackson Pollock, "Number 1A, 1948," Oil and enamel on canvas, 68 x 104 inches. All works by Jackson Pollock © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

This is one of the few large canvases that Pollock painted in his house on Fireplace Road in Springs, rather than in the barn studio, where he began working in the fall of 1946. In fact there’s an eyewitness account by his friend and fellow painter Mercedes Matter. In 1948, she and her husband, the photographer Herbert Matter, were visiting Jackson and his wife, Lee Krasner. Interviewed in the early 1980s for a television documentary on Pollock, she recalled:

“He had a beautiful roll of canvas, and he suddenly decided to take it out. And he took it, and he spread it out on the floor of the living room, which filled the living room. And he went and got paint, and he took the tubes, and he started to paint. He would make the most precise line, right from the tube, squeezing it out. It would be thick, but very narrow and precise, but he was in a sort of trance as he worked. And then after a while, his hands were by then quite covered with paint, he knelt down in the middle of the painting and sort of caressed it with his hands, which had purple all over them, so [he] made hand prints. That was when I watched him paint. It’s the only time.”

.

Jackson Pollock, "Number 1A, 1948," Oil and enamel on canvas, 68 x 104 inches. All works by Jackson Pollock © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

Examining the hand prints carefully, you’ll notice that the index finger of Pollock’s right hand is shorter than you’d expect. That’s because the fingertip was cut off in an accident when he was about 3 years old. He and a couple of older boys were in the barnyard—his parents had a farm outside Phoenix—and Jackson made the mistake of putting his finger on the chopping block while one of them was cutting wood. According to the rather colorful account of the incident in the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, Jackson Pollock: An American Saga, “The little fingertip hit the ground and almost immediately an old bull rooster … waddled over and began pecking at it.”

In addition to the hand prints, Number 1A, 1948 is notable for its combination of artists’ oil colors and enamel house paint. Pollock began to experiment with liquid paint in the 1930s. There is spattered and poured underpainting in The She-Wolf (1943), just visible under the subsequent layers, as well as earlier works not in MoMA’s collection, in which both liquid and conventional paint were used.

Although Pollock became famous for his use of alkyd enamel in masterpieces like One: Number 31, 1950, he never completely abandoned tube paints. In Number 1A, 1948, the oil colors were applied straight from the tube, as described by Matter—squeezed out into ribbons that stand up off the canvas and add dimension to the surface.

People often wonder why Number 1A, 1948 has a letter in its title. That year Pollock had begun to number his paintings instead of giving them descriptive titles, like Gothic (1944) and Full Fathom Five (1947), both of which are in the MoMA show. He explained that numbers are neutral, they don’t suggest what you should be looking for in the picture. “I decided to stop adding to the confusion,” he said, but unfortunately numbering created a different kind of confusion. Since he started with a new Number 1 each year, and didn’t sell everything the year he painted it, keeping the inventory straight was a problem.

So when Number 1 appeared in 1949, the previous year’s Number 1 acquired its letter. In 1953 Pollock went back to naming his paintings, apparently at the insistence of his new dealer, Sidney Janis. Easter and the Totem (1953)—the title was suggested by his East Hampton neighbor, the writer Patsy Southgate—and White Light are examples in MoMA’s collection. And some of the paintings that were originally just numbered later acquired names, so they’re now known by both, like One: Number 31, 1950, in the current show.

Number 1, as it was originally called in 1948, was included in Pollock’s solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in January- February 1949, but MoMA didn’t snap it up on that occasion. It wasn’t until after Life magazine ran a profile of Pollock in the August 8 issue—with the rhetorical subhead, “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”—that the museum decided to shell out serious money for a major canvas.

The article stimulated a burst of sales from his next solo show, in November-December. According to the gallery records, it grossed $5,665 from the sale of 20 works, with most in the $200-500 range. A month after the show closed, MoMA came late to the party, but was more than welcome. Oddly, the ledger entries don’t record the sale of Number 1, which grossed an additional $2,350.

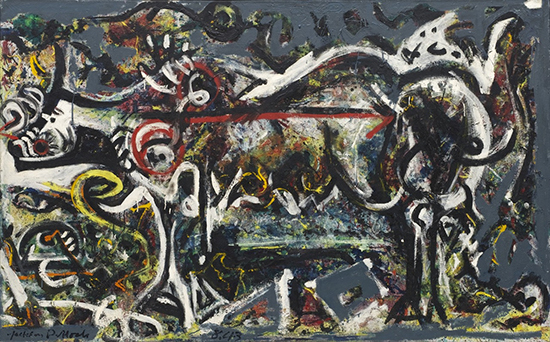

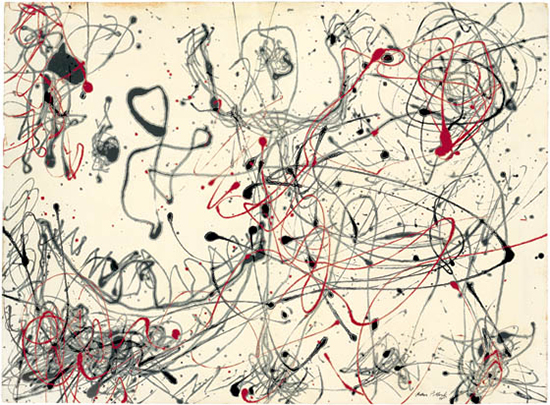

It was not MoMA’s first Pollock purchase. In May 1944, the museum took a flier on Peggy Guggenheim’s young protégé, buying The She-Wolf after his very first solo exhibition at Guggenheim’s vanguard gallery, Art of This Century. They got it for a discounted $600, a considerable amount for a painting by a virtual unknown. (Guggenheim had to inform Pollock of the sale by telegram, since he was too poor to afford a phone.) After waiting a prudent five years, perhaps to be sure Pollock had staying power, in January 1949 MoMA spent $250 on the small oil on paper, Number 4, that was returned in the 1950 acquisition deal. (It is now in the Frederick R. Weisman Foundation’s collection in Los Angeles.) The museum would go on to acquire many more Pollocks, by purchase and donation, and it’s now the foremost repository of his work, with 86 examples in all media except collage and sculpture. The current exhibition includes more than 50 of them, from a cigar box on which Pollock painted a western scene in the early 1930s to the 1954 canvas, White Light, one of his last paintings.

.

Jackson Pollock, "The She-Wolf," 1943. Oil, gouache and plaster on canvas, 41 7/8 x 67 inches. All works by Jackson Pollock © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

Jackson Pollock, "Number 4, 1948: Gray and Red." Oil on gessoed paper, 22 5/8 x 30 7/8 inches. All works by Jackson Pollock © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

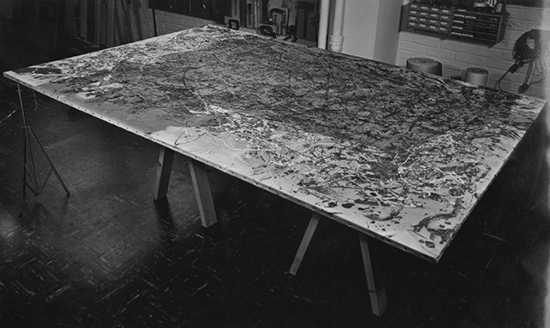

Number 1A, 1948 has undergone two extensive conservation treatments. On April 15, 1958, a fire caused by careless workmen broke out on MoMA’s second floor. Most paintings in the area had been removed during construction, but unfortunately the larger ones were left in place. An 18-foot Monet Nymphéas was destroyed, and the Pollock suffered significant smoke and heat damage. Some of the ribbons of tube paint became brittle and cracked off. The canvas was cleaned and returned to the galleries, where decades of dust and surface grime muted its original intense colors. A second round of treatment in 2014 involved filling in some of the missing oil paint strands, removing dust and discoloration of the canvas, and mounting it on a new stretcher. The transformation is subtle, but as the conservator's blog puts it, “The viewer’s eye no longer lingers on disfigurement due to age or damage. Rather, one simply encounters Pollock’s composition in its entirety, refreshed and restored.”

.

"Number 1A, 1948" during conservation treatment in 1959. The dark area is soot deposited during the fire. Here, conservators have begun to clean the canvas, working from the edges toward the center. All works by Jackson Pollock © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

Looking at the painting now, I’m struck by the way Pollock’s handprints seem to emerge from a swirling cloud of linear filaments, as if someone were trapped in there. It’s the perfect illustration of his belief that “art and life are one.” One critic described this sort of composition as an infinite labyrinth, and Number 1A, 1948, with its maze-like structure, strikes me as a prime example. Unlike those that seem to fold in on themselves gracefully or weave across the canvas at a stately pace, this one thrusts diagonally, pushing toward the corners, then doubling back toward the center, almost tying itself in knots.

.

Jackson Pollock, "Number 1A, 1948," Oil and enamel on canvas, 68 x 104 inches. All works by Jackson Pollock © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

There’s an emotional rawness that’s missing from the more elegant compositions like One: Number 31, 1950 and the Metropolitan Museum’s Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950, although these also communicate the “energy and motion made visible” that Pollock was striving for. It’s less fully resolved than those later paintings, but also more vigorous.

Nevertheless, when Mercedes Matter describes Pollock caressing the canvas, she reminds us that energy is a variable, and motion can be slow as well as fast. In Number 1A, 1948, we have static and dynamic, rapid and measured, impulsive and deliberate, and everything in between.

_______________________________

Helen A. Harrison, the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in East Hampton, N.Y. is a former art reviewer and feature writer for the Long Island section of The New York Times, and visual arts commentator for the NPR affiliate WLIU 88.3FM. Her publications include "Hamptons Bohemia: Two Centuries of Artists and Writers on the Beach," co-authored with Constance Ayers Denne, and "The Jackson Pollock Box," an art kit for young people. Her monograph on Jackson Pollock was published by Phaidon in 2014.

________________________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.