The current “Unfinished Business” exhibition at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill features three iconographic figures of recent contemporary art—Eric Fischl, David Salle, and Ross Bleckner—presenting important works from near the beginning of their careers that cemented their reputations as major players in New York’s creative universe and beyond.

Arriving at a time when the art world was stricken with one of its periodic bouts of suspicion as to whether or not “painting is dead,” in these earlier works the three came to define the move within the art world toward representational expression. This pendulum swing followed years during which figuration had consistently played second fiddle to the dominance of abstraction on the international art scene.

Historically, the question of whether or not the act of painting is dead is a recurring trope among artists and critics, ever since it was first declared by the French painter Paul Delaroche in 1839. The idea has been debated periodically ever since, by authorities as disparate as Kenneth Clark, Jerry Saltz and Gerhardt Richter.

Perhaps not so coincidentally, painting’s demise is usually heralded whenever the intelligentsia seems to grow anxious about keeping one step ahead of the ever-changing cultural zeitgeist that, for good or ill, heavily influences and propels the commercial art market to dizzying new heights.

Fischl, Salle, and Bleckner all arrived in New York around 1978, at a point when declarations of painting’s passing coincided with the decline in popularity of both Pop Art and Minimalism, following those movements’ heyday in the 1960s and early 70s. All three had graduated from the California Institute of the Arts, whose dean at the time, the late Paul Brach, once sardonically described his duties to me as bestowing “licenses to commit art.”

The three artists approached the canvas with markedly different aesthetic priorities and methods. At the same time and more significantly, they shared—despite an array of technical dissimilarities—a desire to return contemporary painting to a more narrative driven framework than artists had opted to apply throughout much of the entire post-war period.

“Unfinished Business: Paintings from the 1970s and 1980s by Ross Bleckner, Eric Fischl, and David Salle” at the Parrish stresses the unique methodologies that established these artists’ stylistic development. The exhibition delineates points of convergence in their work, in particular their focus on social and political issues through a reliance on conjuring an often entertainingly ambiguous narrative framework.

Further, the curators of the exhibit also vividly make the case that the shared personal histories of the three artists and their friendship contributed to their individual creative and aesthetic progression. This despite Lynn Hirschberg’s 1987 article in Esquire magazine, “The Four Brushmen of the Apocalypse,” which suggested that this thesis might be flawed in some instances.

For Eric Fischl, the context of his narrative framework has always been suburbia and suburban values as juxtaposed against the angst and contradictions expressed in relation to prevalent cultural taboos. As stated in many biographical references—including the artist’s own website—his “suburban upbringing provided him with a backdrop of alcoholism and a country club culture obsessed with image over content,” which led him “to become focused on the rift between what was experienced and what could not be said.”

These themes are brought into sharper focus by Fischl’s methodology of framing his images in a manner that is arrestingly cinematic. This kind of framing creates tensions and an interplay between the figures and their placement that is reminiscent of nothing so much as a still frame from an unnamed film.

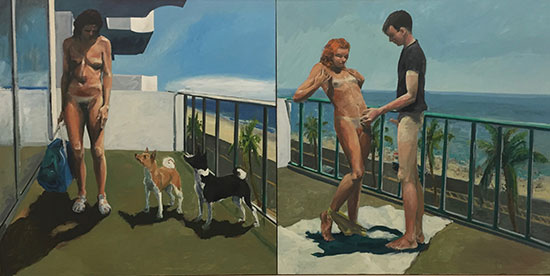

All these elements are in place in Fischl’s Dog Days (oil on canvas, 1983) which, much like his seminal work Bad Boy from the same period, uses nudity and sexuality as a challenge to common perceptions of puritanism while establishing a psychologically equivocal storyline that raises more questions than answers.

.

"Dog Days" by Eric Fischl, 1983. Oil on canvas.

.

This mysterious, and sometimes ominous, opacity in theme is also dramatically apparent in both A Woman Possessed (oil on canvas, 1981) and Scarsdale (oil on canvas, 1986). By contrast, in A Visit to/ A Visit From/ The Island (oil on canvas, 1983), Fischl turns his attention to a plotline that is almost social realist in its political framing. In this work, he examines the issue of white privilege and obliviousness to the harsh realities and tribulations of locals in places experienced by vacationers as a “tropical paradise.”

.

"A Woman Possessed" by Eric Fischl, 1981. Oil on canvas.

.

"Scarsdale" by Eric Fischl, 1986. Oil on canvas.

.

"A Visit To / A Visit From / The Island" by Eric Fischl.

.

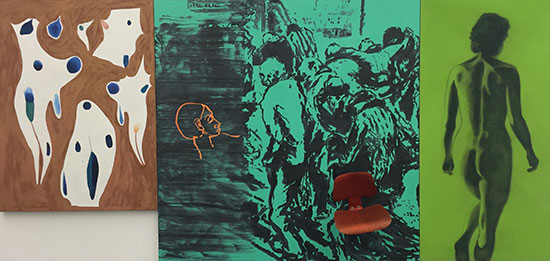

David Salle’s works, on the other hand, create a juxtapositional narrative through his use of both figurative and abstract imagery, a combination made even more effective by the artist’s use of diptychs and triptychs to break up the compositional flow.

Mixing influences such as Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, figuration, Cubism, and Minimalism, Salle is able to present the works as “mirrors” that reflect both the wonders and horrors of contemporary mass media culture, thereby creating in his paintings what Roberta Smith once called “a precarious balance of dystopian and decorative.”

Interestingly, even in their most painterly manifestations, the works nevertheless carry profound overtones of collage in the manner Salle gathers and plays his imagery off against itself. This atmosphere is intensified in works such as The Trucks Bring Things (oil and acrylic on canvas with light bulb and fabric, 1984) in which a functioning electric light serves as a focal point within the canvas, even as the dramatic foreshortening of the painted image beside it dominates the compositional structure.

.

"The Trucks Bring Things" by David Salle, 1984. Oil and acrylic on canvas with light bulb and fabric.

.

This use of collaged materials to orchestrate the composition is also powerful in Poverty Is No Disgrace (oil, acrylic, charcoal, and chair on canvas, 1982). In the mid-1980s, Salle once noted in a lecture in East Hampton that, in this piece, he had “upped the ante on the art world.” Although I’m still not quite sure what he meant by that, I have always liked the painting for the effortless way in which it blends figurative and abstract imagery.

.

"Poverty is No Disgrace" by David Salle, 1982. Oil, acrylic, charcoal and chair on canvas.

.

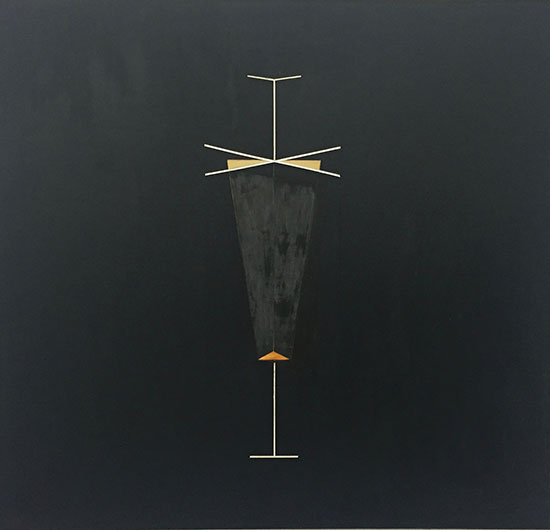

While Ross Bleckner is the most overtly “abstract” painter of the three, his dedication throughout the 1980s to issues of loss and memory offers what is often the least ambiguous painterly narrative. Exploring the emotional toll wrought by the AIDS epidemic, the works focus on solitary emblematic images often imbued with a glowing luminescence that can be read, by turns, as either highly reverential or deeply elegiac.

These overtones echo throughout works like Life of a Lonely Dragon (oil on canvas, 1981) and Flora and the Future (oil on linen, 1983). Other works, such as The Spoilous (oil on canvas, 1981), conjure a dramatic measure of emotional power through the use of geometric imagery. The same is true of Revolver (acrylic and oil on canvas, 1976), in which the central portion of the canvas is occupied by an elegantly ordered configuration which seems to stand at solitary attention like a lonely figure from a Bauhaus stage set.

.

"Life of a Lonely Dragon" by Ross Bleckner, 1981. Oil on canvas.

.

"Flora and the Future" by Ross Bleckner, 1983. Oil on linen.

.

"Revolver" by Ross Bleckner, 1976. Acrylic and oil on canvas.

.

_________________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Unfinished Business: Paintings From the 1970s and 1980s by Ross Bleckner, Eric Fischl, and David Salle” is on view August 7 to October 16, 2016 at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, 279 Montauk Highway, Water Mill, NY 11976. www.parrishart.org

_________________________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.

Excellent insights into and review of these three artists – thank you Eric Ernst