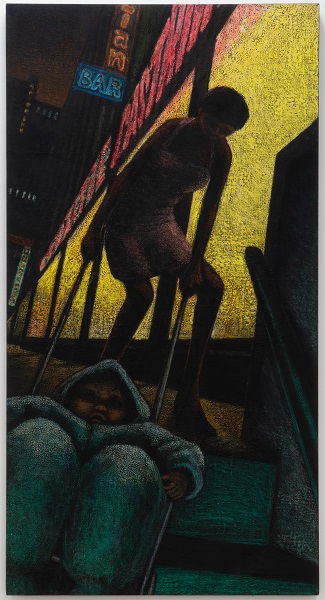

A man lighting a cigarette stands in the red glow of the entrance to a peep show. Cops dart down a city street toward an unseen target. A scantily clad woman drags a stroller up a darkened subway staircase, the shadowed eyes of her chubby-cheeked, snow-suited baby holding the viewer’s gaze.

Each of the paintings in “All That Is Solid Melts Into Air,” by the artist Jane Dickson—at James Fuentes on the Lower East Side in New York through February 17, 2019—is a gritty, gripping story-in-progress set in 1980s Times Square. There are 10 works in total, nine of them large-scale, all displayed in a single white-walled gallery: nocturnal scenes illuminated by the lurid colors of neon signs and the glare of urban lights.

.

"Big Peepland" by Jane Dickson, 2016. Oil on linen, 70 x 44 inches. Courtesy James Fuentes LLC. Photo credit: Jason Mandella.

.

The show is small, but its context is large and layered. The paintings on view are a tiny subset of Dickson’s extensive body of hundreds of drawings, photographs and prints and roughly 80 paintings inspired by her years living in a loft on 43rd Street and Eighth Avenue and recently documented in a lush monograph, “Jane Dickson in Times Square” (Anthology Editions, 2018).

Jane Dickson in Times Square in the 1980s.

Photo credit: Charlie Ahearn. Courtesy James Fuentes Gallery.

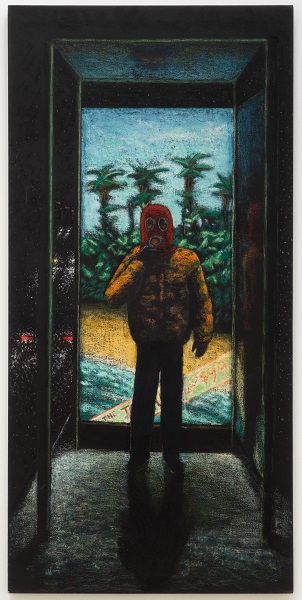

More broadly, Dickson’s “investigation of light out of darkness” can be considered a search for humanity within depravity, pathos within danger. During a recent telephone interview, Dickson recalled the impetus for Bus Stop Boy II, a male figure in a red ski mask completed in 1984.

“I went out to meet Charlie one cold winter night,” she said, “and I came face to face with this person in a bus shelter wearing a ski mask. My first reaction was panic: someone in a mask is innately threatening. Then I realized, ‘He’s like 12 years old. He’s a little gangly, but he’s actually a child, and he’s afraid of me.’ That was a powerful recognition, and I went home and made a drawing of what I remembered, and then I made a couple of paintings from it.”

.

"Bus Stop Boy II" by Jane Dickson, 1984. Oil stick on canvas, 70 x 34 inches. Courtesy James Fuentes LLC. Photo credit: Jason Mandella.

.

Soon after that, Dickson began using a camera to capture the scenes that enticed her. The photographs served as references, bookmarks of place and emotion; sometimes she would return to the spot and have a friend pose to re-create what she had seen. The resulting paintings, including many in “All That Is Solid,” are combinations of multiple photographs, drawings, memory and imagination.

.

"Cops in Headlights" by Jane Dickson, 1991. Oil on linen, 50 1/2 by 36 inches. Courtesy James Fuentes LLC. Photo credit: Jason Mandella.

.

The pieces on view at James Fuentes are from Dickson’s private collection, and are among the few from this body of work that have not been sold. Standing in the gallery, it’s hard not to think of the passage of time. For one thing, the Times Square portrayed by Dickson is gone. “When people talk about these paintings, they talk a lot about nostalgia,” Dickson said. “Because of the gentrification of New York—and, you could say, of almost every city in the world, these places are getting generic and bland, and all their idiosyncrasies are disappearing.”

That fact is reflected in the exhibition’s title. Dickson borrowed it from Marshall Berman’s 1982 book “All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity,” but the line was originally from the first chapter of the Communist Manifesto.

.

"Mother and Child" by Jane Dickson, 1985. Oil stick on linen, 80 x 40 inches. Courtesy James Fuentes LLC. Photo credit: Jason Mandella.

.

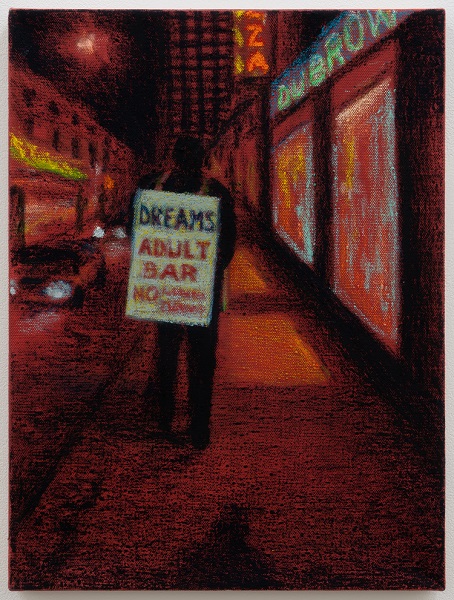

Then there’s the pornography that served as an inevitable backdrop for the paintings, in some cases more explicitly than others. “I was interested in the idea that people put their sexual fantasies out in public,” Dickson said. “It was these primal urges being hung out as signs.”

The sign in Dreams I, proclaiming “DREAMS ADULT BAR,” is the backside of a sandwich board donned by a man awash in garish red light. Two paintings, Big Peepland and Peep VII, expose the world of peepshows. “Those places don’t exist anymore,” Dickson said. “People look at them today and think they’re quaint. Now it’s all online and, in a way, more elusive and dangerous.”

Dickson is expected to speak about these topics on Tuesday, January 29, 2019 at the Museum of the City of New York in “Capturing ‘The Deuce': Times Square in the 1970s & ’80s,” a book signing and conversation with Scott Dougan, production designer for HBO’s “The Deuce,” and New Yorker staff writer Vinson Cunningham.

.

"Peep VII" by Jane Dickson, 1992-1996. Oil and pumice on canvas, 57 x 40 inches. Courtesy James Fuentes LLC. Photo credit: Jason Mandella.

.

Dickson and Ahearn moved from Times Square in 1992 with their then 3- and 6-year-old children, but Dickson didn’t stop making related pieces. The paintings in “All That Is Solid” span from 1984 to 2018, and Dickson shared some thoughts about her changing incentives and perspectives.

Take, for instance, sex. “Now, as an older person, the way I look at it is different from when I was first making this work. Then I could have been that stripper I was painting. Now I am more of a spectator.”

Nevertheless, the topic compels Dickson. “The intersection between sex and gender and commerce—that’s a huge one that comes back and back and back,” she said. “And I’ll realize, there’s a whole other aspect I didn’t explore yet.” So she paints anew. There are images she intended to paint but didn’t, and paintings she now feels need to be part of her canon. “I’ll find there’s something missing,” she said, “and I feel it’s my obligation at this point in my life to look at what I’ve created and fill in those blanks.”

One filled-in blank is Dreams I, from 2018 and the newest work in the show. The painting is based on Dreams Adult Bar, a 1985 drawing of the sandwich-board man on red paper. Dickson said she chose to revisit the subject in order to delve into it further. And, she said, doing so allowed her to reenter a time and place that has vanished. “When I make another version, it's a way to continue to possess it a little longer,” she said.

.

"Dreams I" by Jane Dickson, 2018. Oil stick on linen, 24 x 18 inches. Courtesy James Fuentes LLC. Photo credit: Jason Mandella.

.

Another recent piece is Terminal Bar II, a large-scale iteration of the 1980s Terminal Bar. The original work was small, painted on gray vinyl and sold long ago, a representation of the Terminal Bar across from Port Authority, made with the Son of Sam murders in mind. It was part of a group of paintings that had been realized and exhibited as large canvases. “I always wished I had done a big version of it,” Dickson said.

.

"Terminal Bar II" by Jane Dickson, 2017. Oil on linen, 66 x 73 inches. Courtesy James Fuentes LLC. Photo credit: Jason Mandella.

.

She painted Terminal Bar II in 2017. In the new painting, a man sits in a parked car beside a couple embracing outside the bar. “[Son of Sam] never shot anybody in front of the Terminal Bar, but I thought, ‘This is the end for somebody.’”

Unlike much of the Times Square work, Terminal Bar II bursts with blue. Early on, Dickson composed many of her scenes on a black background. “It was like putting a spotlight on the details I wanted to convey,” she said, “and everything else dropped away.”

But with age came a move toward brighter colors. “Black feels too heavy these days,” Dickson said. “I think that is partly about getting older and not being able to afford the angst of youth. I don’t want that darkness. For now, I’m delighted to be alive.”

.

"Nathans 43rd Street" by Jane Dickson, 1984-86. Oil on canvas, 66 x 78 inches. Courtesy James Fuentes LLC. Photo credit: Jason Mandella.

.

_______________________________

BASIC FACTS: “All That Is Solid Melts Into Air” featuring works by Jane Dickson is on view January 16 through February 17, 2019 at James Fuentes, 55 Delancey Street, New York, NY 10002. www.jamesfuentes.com.

Book signing and conversation, “Capturing ‘The Deuce': Times Square in the 1970s & ’80s,” takes place on January 29, 2019, 6:30-8:30 p.m., at the Museum of the City of New York, 1220 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10029. www.mcny.org.

________________________________

Copyright 2019 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.