The Parrish Art Museum’s latest exhibition, “Image Building: How Photography Transforms Architecture,” is an outstanding exploration of how the camera’s lens modifies the visual experience of built space. Including more than 50 works by 21 artists, the engaging exhibition is divided into three loosely thematic areas: Domestic Spaces, Cityscapes, and Public Places.

On the far wall of the Domestic Spaces gallery, a grid of 12 equally sized photographs makes up Bernd and Hilla Becher’s Framework Houses, 1959-1973. The symmetrical composition and massed linearity of multiple images parallels that of the everyday German houses depicted in the individual prints.

.

Installation view of "Image Building: How Photography Transforms Architecture," on view at the Parrish Art Museum March 18–June 17, 2018. Photo: Jenny Gorman.

.

Rather oddly, one of these houses is shown to have a drainpipe that, instead of running directly down the side of the structure, cuts diagonally across its gable end. Since the ground slopes to one side, there was presumably a practical reason for this slightly eccentric, though not aesthetically displeasing, addition. But in regards to the guiding theme of the exhibition, which was superbly organized by guest curator Therese Lichtenstein, this detail is a kind of cipher.

Framework Houses, like many of the works included in “Image Building,” is absent of people. Even in photographs in which people appear, they are secondary to the architecture. But the interfering human hand is always present, whether it is the photographer or, as in the case of the aberrant drainpipe, an assiduous homeowner. By including photographs of different types of buildings, varying views of the same building, and shots taken during different time periods—from the 1930s up until the present day—“Image Building” skillfully conveys how people always impact architecture and the way it is perceived.

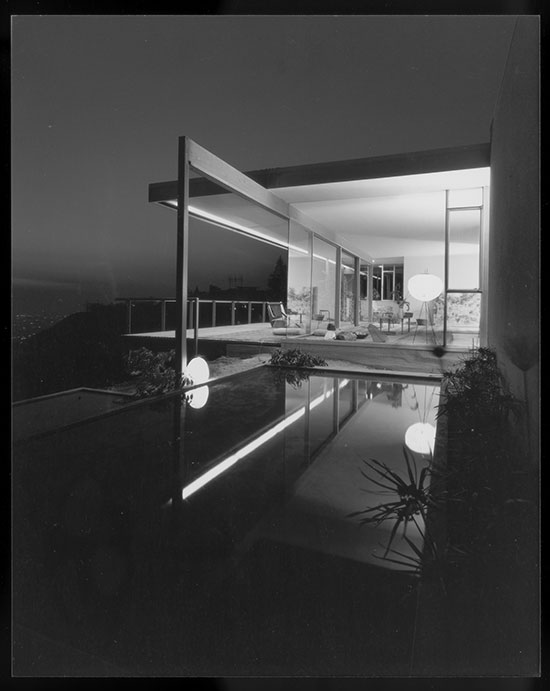

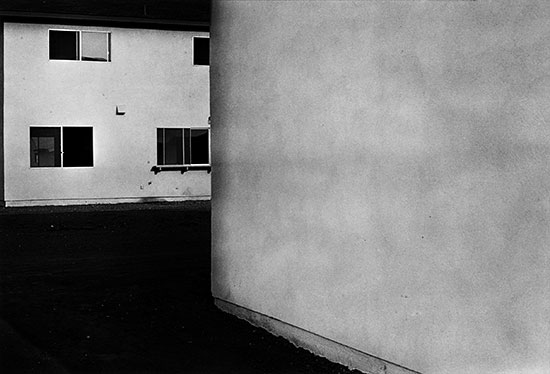

The other works included in Domestic Spaces demonstrate the varying ways individuals approach the built environment. With their clean modern lines, swimming pools, and dramatic views of Los Angeles, the mid-century Case Study Houses photographed by Julius Shulman sell the American Dream. By the late 1960s, though, as evidenced by the images of Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz displayed on the wall opposite, that dream had crumbled. In Adams’s photographs of the Colorado suburbs, cheaply made houses spread vapidly across the landscape, while Baltz captures the banal details of Californian tract homes.

.

"Chuey House" (Los Angeles, Calif.) by Julius Shulman, 1956. Gelatin silver print, 9 15/16 x 7 15/16 inches. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 2004.R.10. © 2018 Estate of Julius Shulman/ J. Paul Getty Trust, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

.

"Tract House #6" from "The Tract Houses" portfolio by Lewis Baltz, 1971. Gelatin silver print, 5 ½ x 8 1/8 inches. George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York. Image courtesy Estate of Lewis Baltz and Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica. © 2018 Estate of Lewis Baltz.

.

Photographs made by Shulman, Adams, and Baltz are all relatively small-scale and black and white, making the placement of the contemporary works that hang alongside them particularly inspired. Hélène Binet’s glorious Christ Church in Spitalfields 02 (Architecture by Nicholas Hawksmoor), from 2013, while also a black and white film photograph, contrasts dramatically in size (60 x 47 inches), subject matter (a striking architectural detail of the 18th century London church), and perspective (dizzying, disorientating) with the four adjacent images from Baltz’s The Tract Houses portfolio (1971). And yet in both cases the surprising manner in which the imagery is presented provokes the viewer to see the architecture anew, just as the photographs maintain their own presence as compelling aesthetic objects.

.

"Christ Church in Spitalfields 02" by Hélène Binet (Architecture by Nicholas Hawksmoor), 2013. Gelatin silver print, 60 x 47 inches. Courtesy Ammann Gallery, Cologne, Gabrielle Ammann. © 2018 Hélène Binet.

.

James Casebere’s 2016 photograph, Yellow Overhang with Patio, also expresses a sense of objecthood, but in this case the built space looks fake, like a painted backdrop of a movie set. By constructing table-top models of his depicted environments using everyday, disposable materials such as cardboard and Styrofoam, and by manipulating the effects of light and shadow, Casebere’s photographs exist in the suggestive realm of narrative.

.

"Yellow Overhang with Patio" by James Casebere 2016. Archival pigment print mounted to Dibond, 44 3/8 x 66 1/2 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly, New York. © 2018 James Casebere.

.

Yellow Overhang with Patio was among a series of new works exhibited last year at Sean Kelly Gallery that was inspired by the “emotional architecture” of Luis Barragán. Moving beyond the purity of Modernism, the Mexican architect injected his designs with color and warmth. Hanging side-by-side with Shulman’s black and white promises of Modernist dream homes, Yellow Overhang, with its bold coloring and tenuous reality, calls into question the certainty of that promise.

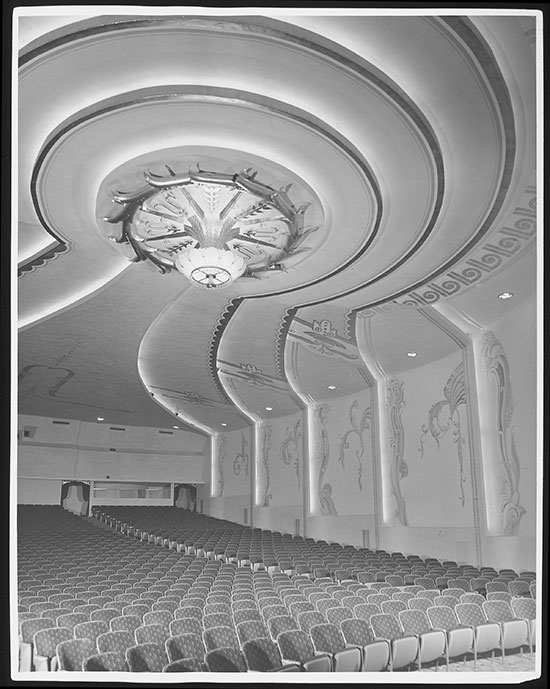

Aside from the stand-alone excellence of many of the photographs included in “Image Building,” the exhibition’s visual and thought-provoking richness is assisted by the way it establishes a complex web of connections between artists, architectural structures, and artistic approach. For instance, the gallery adjoining Domestic Spaces, designated Cityscapes, also contains a work by Julius Shulman. Here his 1960 interior view of the Academy Theater in Inglewood, California, is juxtaposed with Hiroshi Sugimoto’s dramatically different take on Radio City Music Hall’s interior in 1978. While the former presents a clear view of the creamy whiteness and elegant lines of the theater’s auditorium, the latter casts this area in darkness to focus on the brilliantly lit, but eerily empty, stage.

.

"Academy Theater, interior" (Inglewood, Calif.) by Julius Shulman, 1960. Gelatin silver print, 10 3/16 x 8 1/16 inches. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 2004.R.10. © 2018 Estate of Julius Shulman/ J. Paul Getty Trust, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

.

"Radio City Music Hall, New York" by Hiroshi Sugimoto. 1978. Gelatin silver print, 47 x 58 ¾ inches. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York. Image courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco/ Marian Goodman Gallery, New York. © 2018 Hiroshi Sugimoto.

.

Meanwhile, in the corridor that connects the exhibition’s three galleries, and which includes a section devoted to Iconic Buildings, is a further view of the Academy Theater by Shulman, but here the photographer presents its funfair-like exterior. In capturing the theater’s upcoming events as announced on its billboard, including “Cash Club/Wednesday/500 Dollars,” and “Frank Capra’s Greatest,” the 1940s photograph conveys something of the cultural ethos of the time.

A similar era-defining spirit suffuses the accompanying photographs of other buildings that characterize modern America, such as Kennedy Airport’s Eero Saarinen-designed TWA Terminal, as photographed by Balthazar Korab and Ezra Stoller in the 1960s, when it was brand new.

Stoller also makes an appearance alongside Sugimoto back in Cityscapes, where, in another smart curator choice, the two artists’ depictions of Le Corbusier’s Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut of 1954 are presented side by side. Stoller’s photograph, taken in 1955, is a small, documentary-style image that allows the striking design of the newly completed chapel to speak for itself. Sugimoto’s 1998 image, on the other hand, is a more subjective response to Le Corbusier’s masterpiece. By zooming in on a section of the chapel and blurring the focus, the photographer creates a wonderfully disorientating, sweeping effect. In so doing, Sugimoto replicates the phenomenological and meditative experience of the chapel in pictorially poetic form.

.

"Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp Chapel, Le Corbusier, Ronchamp, France" by Ezra Stoller, 1955. Gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 inches. Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York. © 2018 Estate of Ezra Stoller/Esto.

.

"Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut" by Hiroshi Sugimoto, 1998. Gelatin silver print, 58 ¾ x 47 inches. Courtesy the artist. Image courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco/ Marian Goodman Gallery, New York. © 2018 Hiroshi Sugimoto.

.

Such varying photographic perspectives of architecture and the built environment are found throughout “Image Building.” Other works in Cityscapes, such as Berenice Abbot’s The Night View, 1934/1974, and Samuel H. Gottscho’s Southeast from the RCA Building, 1934, are classic black and white nocturnal vistas of the New York City that one dreams of. Likewise, Iwan Baan’s, now color, aerial shot of Manhattan in The City and the Storm, 2012, still captures New York’s captivating pull. But taken in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, and showing the vast area of the city subsequently plunged into darkness, it is a sobering reminder of the fragility of the human-built in the path of nature.

.

"The City and the Storm" by Iwan Baan, 2012. Chromogenic print, 72 x 48 inches. Courtesy the artist and Moskowitz Bayse, Los Angeles. © 2018 Iwan Baan.

.

While the notion of “public” is not strictly adhered to in the final gallery designated Public Places, its series of large-scale compositions invites the viewer to further consider societal interaction with architecture. From the mesmerizing replication of apartment windows in Andreas Gursky’s Avenue of the Americas, 2001, which captures both the interconnectedness and the loneliness of city life; to an exploration of the way historical spaces are experienced by the contemporary public in Thomas Struth’s Pergamon Museum I, Berlin, 2001; to a consideration of ubiquitous Stepford Wives-like housing estates as brilliantly conceived by James Casebere in Landscape with Houses (Dutchess County, NY) #2, 2009, the collected photographs offer myriad ways of contemplating the shaping influence of architecture, and its photography.

But to return to the start. Hanging next to the Becher’s Framework Houses is the photograph that serves as the exhibition’s title image, Torre David #2, 2011, by Iwan Baan. This striking work demonstrates sublimely how architectural meaning is transformed both by human use and by the photographer’s lens. The work is part of a series depicting a luxury Caracas skyscraper that, after the Venezuelan banking crisis in 1994, was left unfinished by its developer. Eventually, with such a dire lack of housing available in Caracas, people began to move in to the abandoned building, creating homes and a community.

Shot from below, looking up through the tower’s circular atrium, Baan captures the building’s intended grandeur and the brutality of its raw, unfinished space. But Torre David #2 also reveals the influence of its inhabitants through such details as a lime-green painted balcony, curtain-adorned windows, and the precarious-looking placement of pot plants on a ledge, while barely-in-focus children regard the viewer from their concrete lookout. The combination of these humanizing details and the visual vortex created by the architectural structure, the camera angle, and the dark, cloud-filled sky, though somewhat unsettling, ultimately evoke the awe-inspiring possibilities of a community-created, secular cathedral. With “Image Building,” Ms. Lichtenstein and the Parrish have created an equally exhilarating show.

.

"Torre David #2" by Iwan Baan, 2011. Chromogenic print, 48 x 72 inches. Courtesy the artist and Moskowitz Bayse, Los Angeles. © 2018 Iwan Baan.

.

_____________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Image Building: How Photography Transforms Architecture” is on view March 18 to June 17, 2018 at The Parrish Art Museum is located at 279 Montauk Highway, Water Mill, NY 11976. http://parrishart.org

Public Programming includes a series of three "Inter-Sections: The Architect in Conversation." On Friday, April 6, 2018 at 6 p.m., exhibiting photographer James Casebere will discuss Constructed Photography; on Saturday, April 14, 2018, at 5 p.m., exhibiting photographer Iwan Baan converses with architectural historian, curator, writer and critic William Menking; and on Friday, April 20, 2018 at 6 p.m., architect Lee H. Skolnick, photographer Ralph Gibson and curator Therese Lichtenstein will discuss "Flattened Space."

______________________________

Copyright 2018 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.