For the 26th installment of the IFPDA Fine Art Print Fair, at the cavernous Javits Center, a notably selective group of 81 dealers has managed to secure the quiet intimacy within their spaces that is conducive to the close examination of the finer details of major works. On view are prints by canonic figures such as Durer, Rembrandt, Munch, Picasso, Miro, Gauguin (a newly discovered work), Freud and Hockney, alongside a subtle but stimulating selection of fresh new commissions and projects by contemporary artists including Tara Donovan, Laure Provost and Julie Mehretu.

Even though traffic was heavy during the VIP preview October 25, the decibel level was vastly lower than the usual art fair as white-gloved gallerists meticulously presented sheets as well as rare books gently removed from their frames or slipcases for inspection. For one reason or another, it seemed that the London galleries had the most to offer; perhaps it is a matter of temperament. Print people, like photography collectors or organists in the music world, have their own marvelous obsessions with materials, process and conditions. In the end, it comes down to ink on paper.

Even after visits to a few of the leading ateliers (including Ken Tyler’s laboratory-like “perfect studio” in Mt. Kisco), my most valuable lesson in the magic of printing came from a press check during the run of a glossy magazine. As the sheets would course through huge presses, the pressman showed me, under a loupe, how “dot gain” would spread from one point of ink into the next. It was this lesson in the interaction of color worthy of Seurat or Albers that guided me through my close examination of major works by Diebenkorn, Lichtenstein and LeWitt at the fair.

The “trade show” ambience of the venue, the River Pavilion of the Javits, was belied by this scholarly focus, but I was still reminded of Claes Oldenburg’s pizza analogy for printing, as told to Richard Axsom in 1996: “You could say making a print is like preparing a pizza. You start with a white sheet of paper—that is, the ‘dough’—to which you add layers of images: cheese, mushrooms, sausage bits, tomato paste, immersed in overprinted inks. In the end the ‘pizza’ is ‘editioned’—that is, sliced and distributed for consumption.” Putting Oldenburg’s cynicism aside, for this reviewer the following were the five best offerings at this year’s fair:

Edvard Munch at Frederick Mulder

It is amazing the psychological impact that can be exerted by a print, which lays its own claim to being a masterpiece even if it is qualified by the idea of being a “multiple.” The absolute heart punch of the fair for me was delivered by Edvard Munch’s The Sick Child, the artist’s maiden voyage into color lithography.

.

"The Sick Child I" by Edvard Munch. Lithograph. Courtesy of Frederick Mulder.

.

Like Giacometti, Munch exploited the atmospherics of the scribbly, echoing line to add emotional and visual resonance to a portrait (as he did in the similarly delicate portrait of the poet Stéphane Mallarmé). The work was printed in 1896 from four stones, the “keystone” printed in black followed by grey, yellow and red. The crisper outline of the girl’s face, traced in black, is reminiscent of the clean silhouettes of Toulouse-Lautrec and early Picasso. The foggy grey and hazy yellow surround her in expressionist angst. The coup de grace, however, is delivered by the red, which flows down her hair and dangles before her eyes. Its effect is riveting. According to the gallery, the artist considered the work to be his greatest moment in the medium.

The same booth has a rare Picasso print, the rough-and-tumble La Minotauromachie, that was never released to the public but reserved only for private distribution to important contacts. As dense as a late-state Rembrandt etching, and as full of incident as one of his Ballets Russes theater set designs, it is a five-act drama on a sheet of white paper.

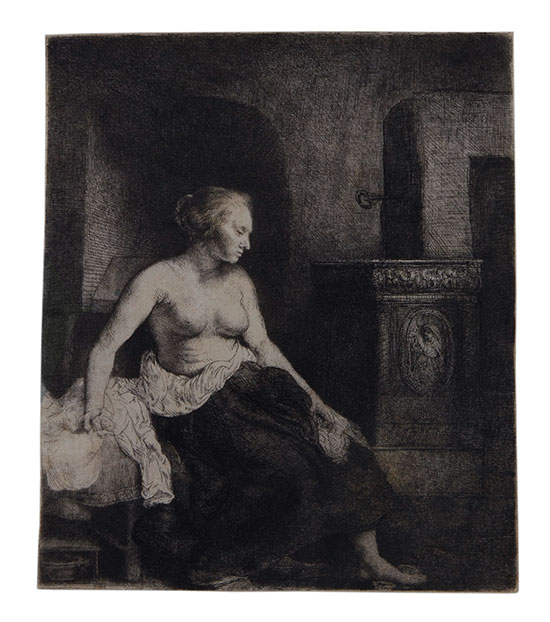

Rembrandt at David Tunick

I can always count on David Tunick bringing out the big guns for an occasion this momentous, and the Rembrandt nude (sensibly sitting by a stove, decorated possibly with a kneeling figure of Mary Magdalene) made in 1658 is certainly one of the biggest. There is something almost wistful about her sleepy downward glance, and the shadows alone are epic displays of cross-hatching.

.

"Woman Sitting Half Dressed Beside a Stove" by Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, 1658. Etching, engraving, and drypoint on Japanese paper. Courtesy of David Tunick, Inc.

.

Etching had been around a century before Rembrandt took it up, and revolutionized it (even Van Dyck, who followed closely yet relied on assistants to finish the plates, did not alter the medium as the master had) by using mordant acid, which bites the plate slowly, by contrast with nitric acid that works fast and spreads, widening the lines. This made an image like the one on view all the more like a line drawing. Experts feel that the work, laborious and painterly, was not completed in one sitting, and late states show dramatic alterations. The darker the better with Rembrandt etchings, in my opinion, and this is one of the darkest beauties of the master.

Richard Diebenkorn at William Shearburn

Like a moth to the flame, I gravitate to Diebenkorn’s blues as helplessly as I would to a Matisse Moroccan painting (the kinship is self-evident). The woodcut made in 1984 is so saturated in the bright California-sky blue of his Ocean Park palette that it is easy to skip the band of gold at the right edge, or the powdery white veils across a geometric figure near the center.

.

"Blue" by Richard Diebenkorn, 1984. Woodcut in colors on Mitsumata Paper. Courtesy of William Shearburn Gallery.

.

Better known for his etchings, Diebenkorn (under the aegis of Crown Point Press, which published his prints along with Tamarand Lithography and Gemini G.E.L., headed to Japan in the 1980s to try woodcuts at the Shi-un-do Print Shop in Kyoto. The textures as well as the vibrant palette of the work are, like Helen Frankenthaler’s work in woodcuts, extraordinary achievements in late-career experiments.

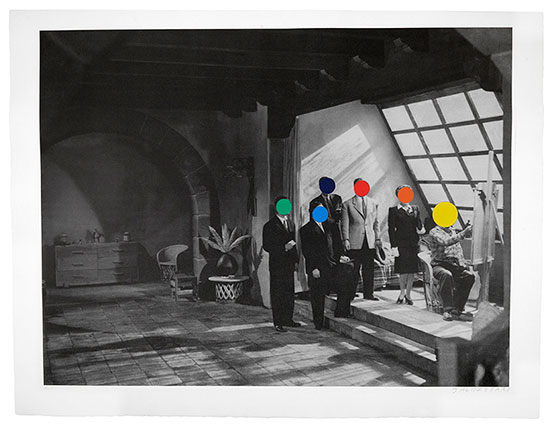

John Baldessari at Sims Reed

The wry reinterpretation by John Baldessari of the stiffly posed group portrait of artists and kibitzers in the studio that was so popular in the 19th century has some of the provocative ambivalence of a Mark Tansey painting. Both play that meta-critical card, reflecting on the art scene from within. The approach is all the more ironic in that Baldessari called his notorious CalArts course the “post-studio class.” An offset lithograph made in 1988, it floats his signature yellow, orange, blue and black dots on the faces of Fifties-era models posed like movie actors under a vast skylight while a man mimes painting.

.

"Studio" by John Baldessari, 1988. Lithograph with colour screenprinting, 74.8 x 96.5 cm. Courtesy of Sims Reed Gallery.

.

I lingered at the London-based Sims Reed booth not just for the prints but for the rare books as well, conveyed in hushed ceremoniousness from a rear area and lovingly opened only for the serious inquisitor. Among the book treasures was “Salvo for Russian,” a volume edited and published in an edition of only 100 to benefit the cause of women and children suffering in the Soviet Union after the German invasion. It was created by the ocean liner heiress and Jazz Age muse Nancy Cunard (her boyfriends included T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and Samuel Beckett). It includes two of her too-neglected lyric poems as well as wonderful etchings by John Piper, John Banting, Mary Sykeham, Roland Penrose, Julian Trevelyan and others. It was on the shelf along with illustrated books featuring Jean Cocteau, Giorgio de Chirico, Marc Chagall, Sonia Delaunay and Blaise Cendrars. I could have browsed for hours, and resolved to visit the gallery when next in St. James’s.

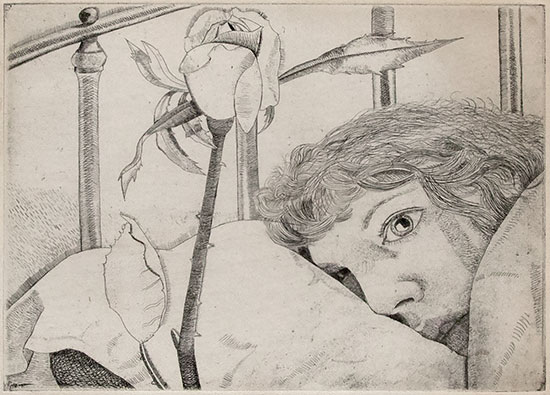

Lucian Freud at Mary Ryan

That one-eyed gaze, that long-stemmed thorny rose, the tousled hair, the exquisitely rendered pillow and brass headboard. The subject is Kitty Garman, the artist’s first wife. We are in Freudian territory with this provocative etching, made in Paris in 1948, on view at Mary Ryan. It was created at the culmination of a brief exploration of the medium, which he started using in Paris in 1946, then gave up for more than thirty years to focus on painting in oil.

.

"Ill in Paris" by Lucian Freud. Etching. Courtesy Mary Ryan.

.

Freud returned to printmaking in 1982, but the historical interest of this work is its date—the artist made only six etchings between 1946 and 1949. That was the year he abandoned the medium for several decades; these works play an important role in his oeuvre. It was works like this that prompted the critic Herbert Read to call Freud "the Ingres of Existentialism."

____________________________

BASIC FACTS: IFPDA Print Fair 2017 runs from October 25 to 29, 2017 at the Javits Center.

River Pavilion, 35th Street and 11th Avenue, New York 10001. Tickets for Print Fair and events start at $10 and are limited. www.printfair.com

____________________________

Copyright 2017 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.