It takes a brave and savvy gallery to train the spotlight of a retrospective on the living legacy of William T. Williams, whose last New York show was more than four decades ago. Thanks to the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, in hard-edged color abstractions of the 1960s through vastly more expressionist canvases of just last year, the perfectionism of Williams is now taking its star turn in Chelsea.

Because the large-scale, brilliant-hued earliest works need plenty of white wall, the show is hung in reverse, starting deep in the space and moving chronologically toward the door. A pair of slender vertical canvases from 1968, titled J.D. and Harlem Angels, unfolds the illusion of an architectural space that combines the optical wit of M.C. Escher with the clean, taped edges of Frank Stella.

In geometric abstraction, form and color lock together in puzzles, while nuances of brushwork lend a more personal energy. Theme and variation is a path to developmental change that favors incremental transformations over wholesale disruption. When it succeeds in music, design or even business the process leads recursively to wholesale metamorphosis via steps that offer a rare intimacy with the artist – thinking alongside Bach or Cezanne as he or she takes another run at the motif from fresh angles.

In the work of Williams, the choice of theme is crucial, and sometimes the simpler the phrase the better, because the layers of complexity build rapidly. The kite-like form at the core of the hard-edged paintings, and specifically the acute angles inside its triangular parts, offers a geometric basis. This diamond shape, the artist noted in a gallery press release, functioned “as a stabilizing force, a form that interacts compositionally with what's around it. But it goes back to the quilts of my childhood, the patterns and forms I grew up with.”

Pursue this theme through the major and minor variations of the 1970s. First it soars in bold fire-engine red in Mercer’s Stop, a major painting made in 1971, then dives under the monochrome and textured surface of Nu Nile (painted two years later) and passes even more subtly under the “roller” marks (as he calls them, for the tool that made them) of Midnight Oil, from 1979. The triangle remains the formal string that keeps the kite form from breaking away completely in the breeze of inventions and interventions. One section of Mercer’s Stop is covered in a delicately feathered passage that he called his “shimmer,” which laid the groundwork for the next phase in Williams’s career, a series that relied heavily on this technique, often across monochromes.

.

"Mercer's Stop" by William T. Williams, 1971. Acrylic on canvas, 108 x 84 inches. © William T. Williams; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

.

When it became clear to me that Williams had shifted gears dramatically from decade to decade, I started searching for the transitional pieces that bridged different styles. In Midnight Oil the triangular forms, pale and deeper oranges, slip in and out of focus on the three-part composition (all on one canvas in this case, but Williams also used joined canvases to great effect in other works). On the left panel of the painting the edges of the triangles are subsumed in heavy acrylic under the “roller marks,” and the transition from the highly reflective “shimmer” to a light-absorbing matte finish is achieved in part by the addition of chalk to the paint, dulling the surface down to a finish that resembles encaustic.

.

"Midnight Oil" by William T. Williams, 1979. Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 60 inches. © William T. Williams; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

.

Together with allusions to John Coltrane and other jazz greats, Williams is a dab hand at literary references, the most suggestive being A Note to Marcel Proust, a densely packed and ambitious work in which raised hands seem to grow from the muddy soil of grays and maroons at the bottom. The palette and consistency of the acrylic in these, so different from the tight, flat look of the hard-edged works, reminds me of the thick glop of Sean Scully. Intentionally or not, the Proustian reference is apt because the integration of past and present in the multi-part paintings of Williams has that conjoined sense of anticipation that was the hallmark of the French author.

.

"A Note to Marcel Proust" by William T. Williams, 1984. Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 54 1/4 inches. © William T. Williams; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

.

With five decades of work to choose from, the show takes on the challenge of being an edited retrospective, and it almost feels like a group show by virtue of the shifts in idiom. The work on view begins, chronologically, with hard-edged abstraction, which yields to the more gestural “shimmer” paintings that succeeded it before moving on to the dense, messy (in a charming way) expressiveness of the present (Williams works in New York and Connecticut). Although abstraction and impersonality are often paired, I paid extra attention to the biography just because the intellectual preparation for the artist’s work was so formidable.

What a life Williams has led. When he was a child he and his family moved to New York from rural Cumberland county in North Carolina. After prepping at what was then called the School of Industrial Art (now the High School of Art and Design), he moved on in 1962 to Pratt Institute, where his teachers included Richard Lindner, Philip Pearlstein and Alex Katz, all major figurative painters. He progressed to graduate study at Yale University, at a time when the place was turning out art stars by the boatload—Richard Serra, Sol LeWitt, Robert Mangold, Judy Pfaff and many others came out of the Josef Albers class on color theory.

Williams studied under Jack Tworkov and Al Held, and the unrelenting precision of Held can be seen in the early work particularly. As Williams recalled, in the press release for the show: “Held was relentless in terms of pushing me … it was really good for me because it forced me to focus on what I wanted to do and why I was doing it.”

After finishing his MFA in 1969, Williams moved to New York and by 1969 he had a piece at MoMA, was included in the Whitney Biennial and was helping to curate an important show at the Studio Museum in Harlem, where he helped found the artist-in-residence program that is still going strong. His loft on Broadway was in the thick of the Soho scene, and his neighbors through the years included Kenneth Noland, Joel Shapiro and Janet Fish.

Eventually he taught at Brooklyn College and Skowhegan, which is honoring his service to the Studio Museum in Harlem this year. As a mark of his early success, his work was featured in H.W. Janson’s canonical “History of Art,” the standard textbook in survey courses. At the time of his inclusion, he was the lone African-American in that reference volume. He has won a Guggenheim, and has work in the permanent collections of the Detroit Institute of the Arts, the Fogg Museum at Harvard, the Menil Collection in Houston, and the Whitney.

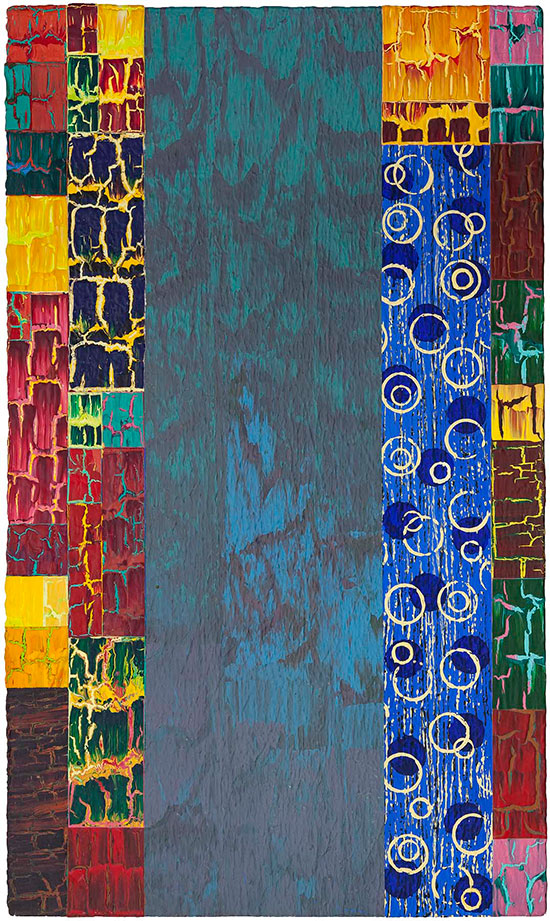

The minor miracle of the show is the late burst of color and texture in the recent work, such as the dense patterning and thick impasto of Joe’s Joy (in which the fascination with quilts is particularly evident). The passages that held my attention were the seams where the “bricks” are joined. The beaded paint that braided veins of color reminded me of the pulsing welds David Smith used as compositional elements, fusing the steel plates of his sculpture. Even among big, bold color abstractions, the old adage “magnum in parvo” (“great things in small”) holds true.

.

"Joe's Joy" by William T. Williams, 1982-2003. Acrylic on canvas, 75 1/2 x 45 5/8 inches. © William T. Williams; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

.

Down a little corridor from the desk, away from the main rooms of the show, is a small improvisatory acrylic on Masonite titled Blue Obey. The calligraphic ribbons of white that dance across the indigo of the background made me think of an entretien between Philip Taaffe (figure) and Howard Hodgkin (ground). During an art season when identity politics has become particularly obtrusive, I prefer the paintbrush to the hammer, especially when the instrument of beauty is handled with the finesse of William T. Williams.

.

"Blue Obey" by William T. Williams, 2007. Acrylic on Masonite, 21 3/4 x 18 1/8 inches. © William T. Williams; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

.

_______________________________

BASIC FACTS: “William T. Williams: Things Unknown, Paintings 1968-2017” is on view from April 7 to June 3, 2017 at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, 100 Eleventh Avenue @ 19th, New York, NY 10011. www.michaelrosenfeldart.com.

_______________________________

Copyright 2017 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.