Ah, a beautiful show to review. Those of us who speak about things that are inherently silent regularly trudge off dutifully to gallery shows with guarded expectations, hoping to find quality north of finger painting and an installation that doesn’t resemble a grad student’s notion of chaos theory.

That hope is realized too infrequently. Hence the true pleasure of attending the photography show, "A Democracy of Images" currently installed at the Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York.

“A Democracy of Images” is curated by the reliable Colin Westerbeck, apparently drawing mostly from the extensive materials owned by the gallery. In Westerbeck’s view, the exhibition includes “underappreciated photographs by famous photographers and great photographs by underappreciated photographers.” No one will disagree.

The photographs on view are older film camera work dating back to as early as 1860 for a Francis Frith albumen landscape print, but mostly are concentrated in early and mid-20th century photojournalism. No one photographer has more than three prints and the total count is around 100, explaining the inclusive title. Best to set aside some unhurried time for this show.

Westerbeck has been a major player on the photography scene. From 1986 to 2003 he was a Curator of Photography at the Art Institute of Chicago; from 2008 until 2012 he served as the director of the California Museum of Photography at the University of California, Riverside. In addition he has written about photography and taught extensively on the subject. A book with the same title as this exhibition is expected soon, with an essay by Westerbeck.

In a departure from the trend among contemporary photographers—such as Andreas Gursky, for one example—to produce billboard size prints, the show consists mostly of older and smaller works, providing the viewer with a more intimate experience than what I have seen recently at photography shows.

The darkroom equipment used for these film images was unable to print much larger than the works on view, and most of the images were made for books or newspapers anyway. Photography at the time was a bit on the margins, as it was machine made and not thought of as equivalent to other forms of fine art, with its diminution a contributing factor.

Curiously, things have flipped and today and many artworks in general often begin as an assemblage of photography. For example, figurative paintings are routinely traced from projected photographs tweaked in Photoshop. Architects photograph models and then “place” their buildings on the site via photographic manipulation, making structural changes as the reproduced surroundings dictate.

This is a roundabout way of describing the compelling feature of this show: These older images were birthed at a time when the expectations for their significance was low; yet now, with photography the mainspring for art endeavors everywhere, they glow with a new importance. Back to the future.

Frith’s mountain shot, Chamounix (now spelled Chamonix), taken in the Chamonix Valley in France, is the oldest work in the show and one of the few included landscape works. The quiet sepia tone and soft resolution typical of lenses at that time bring it closer to being a miniature painting than a photograph.

It’s easy to view Frith’s images with sentimentality as they seem to show the open spaces of a new, unspoiled and uncrowded country. Other photographers from this time document the rapid industrialization and population increase already underway in Western Europe.

.

“Chamounix” by Francis Frith, 1860s. Albumen print. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

.

Paris 1860s, Boulevard St Martin, Photographer Unknown. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

.

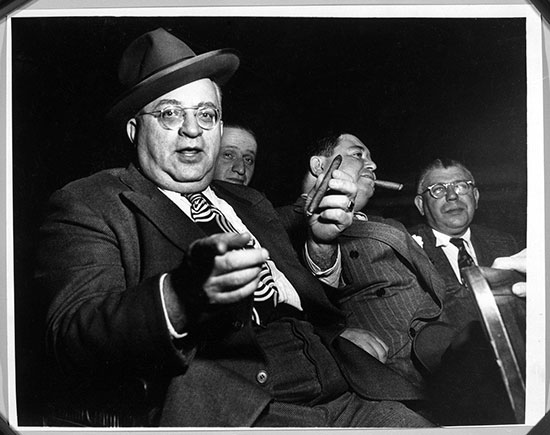

Tammany Hall was a name given to a political offshoot of the Society of St. Tammany, a club founded circa 1789 for self-described “pure Americans” who took the name of a Lenape Native American “Tamanend” and referred to their meeting hall as a wigwam. (Lest anyone think the modern age has a monopoly on silly politics.)

This largely Irish Catholic society became synonymous with the New York City Democratic political party and hand picked city and state politicians for nearly two centuries. Along the way the Tammany clubs and ward system helped new Catholic Irish immigrants move upwards, but ultimately Tammany Hall became a metonym for corruption due to the mid-19th century reign of William "Boss" Tweed.

The multigenerational political machine was still going strong in 1947 when Arthur Leipzig snapped his perfect Tammany Hall, which shows all the self-assurance and menace of this famous political club.

.

“Tammany Hall” by Arthur Leipzig, 1947. Gelatin silver photograph. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

.

The director Alfred Hitchcock was out of sync with his time, with his best efforts typically screened as one of the B-movies at the drive-in. His masterpiece “Vertigo” (1958), for example, saw the Academy Award for Best Picture go to “Gigi,” a light musical by Vincente Minnelli. Later, his brilliant “Psycho” (1960) was not even nominated, losing to the first super-spectacle, “Ben Hur.”

After the world caught up to him and he became the seminal hero of the following filmmaker generation, he famously lamented that his films “had gone from failures to masterpieces without ever having been a success.” On view at Howard Greenberg is an early 1942 Gjon Mili strobed photograph of the rotund Hitchcock (probably taken for Time/Life, given the copyright on the print) the year he made “Saboteur,” one of his most riveting “failures.”

.

“Alfred Hitchcock” by Gjon Mili, 1942. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

.

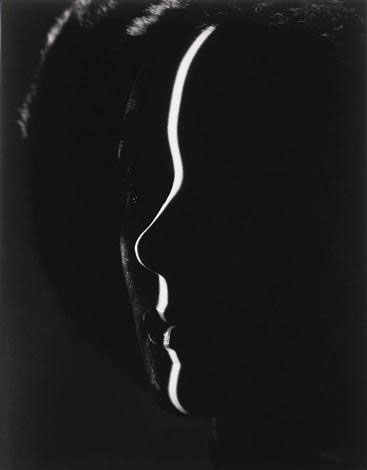

A point of interest: The most expensive photograph in the show, with the asking price of $150,000, is the Shadow Profile by Erwin Blumenfeld (1897–1969) taken in 1944. Blumenfeld, a German, brought a modernist paradigm to fashion photography, creating a signature look that has made him a clear collectible. I was unable to find any previous public sale near this asking price. A print from this image sold last May at Sotheby’s London for $74k, including buyer’s premium, so I can imagine the gallery might be willing to dicker.

All in all a good showing curated by Colin Westerbeck at the Howard Greenberg Gallery. Put it at the top of your list.

.

“Shadow Profile” by Erwin Blumenfeld, 1944, New York. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

.

______________________________

BASIC FACTS: “A Democracy of Imagery,” curated by Colin Westerbeck, is on view March 24 through April 30, 2016 at the Howard Greenberg Gallery, Suite 1406, 41 East 57th Street, New York, NY 10022. www.howardgreenberg.com.

______________________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.