Surprises and studio secrets emerge in two exhibitions of drawings on the Upper East Side in New York City. In “Color(less)”, presented in the upper-story townhouse space of Van Doren Waxter, a single room of drawings reveals decades of studio secrets ranging from abstract expressionism and surrealism through minimalism. Inspected closely, most are not what they seem from a distance, packing small shocks in the hushed atmosphere.

At the nearby Frick Collection, studio secrets from an earlier age are revealed in “Andrea del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action”.

.

"Color(less)" at Van Doren Waxter. Courtesy of Van Doren Waxter.

.

The wit at the heart of the “Color(less)” show springs from the juxtaposition of a trio of understated (even for minimalism) studies that are as conceptual as they are graphic, until it is time for their close-up: A Red Line of Random Length and Drawn from the Left Side of the Page (1974) by Sol LeWitt; Drawing Which Makes Itself (RP#3) (1973) by Dorothea Rockburne; and a Donald Judd pencil plan for a sculpture.

Lewitt was in the famous “uber-class” at Yale taught by Josef Albers (among the many other students were Richard Serra and Robert Mangold, whose drawings are also in this show). The Bauhaus master had a parlor trick for his students that demonstrated his amazingly steady hand. He would place a point at the right end of a long chalkboard then, freehand, draw a (reputedly) perfect line to it. The crisp, red line of LeWitt’s drawing, which does indeed enter stage right and proceed to what seems to be about the midpoint of the sheet, is unnervingly straight and then arrives at a clean, clear stop.

Hung low on the wall so that the line is about waist high for this viewer, the gesture was as much mental as physical, which seems appropriate given that many consider the point of LeWitt to be the conceptual nature of his work.

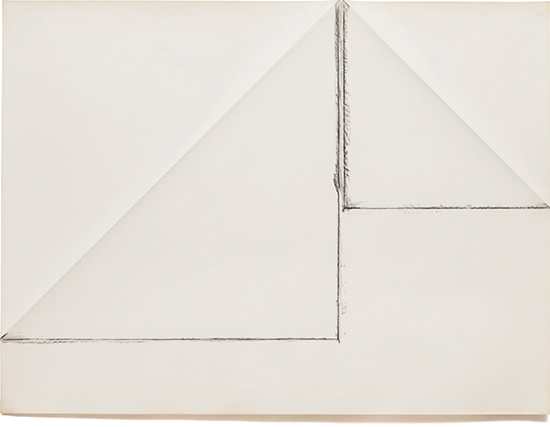

Some of the same twist is found in the piece by Rockburne, that magician of mathematical proportion whose Mozart paintings from the period when this drawing were made are pure evocations of ideal form. Using immaculately folded white paper and a few, Picasso-like black lines, she builds the essential architecture of a pyramidal structure. Then I noticed the superbly human touch of the charcoal strokes, chugging their way upward along the vertical axis and, on its other side, passing back and forth, as expressive as the whole was under control.

.

"Drawing Which Makes Itself (RP #3)" by Dorothea Rockburne, 1973. Charcoal on paper, Framed Dimensions: 30 x 40 inches. Courtesy of Van Doren Waxter.

.

Next to these two, and clear as an engineer’s blueprint, while at the same time as enigmatic as a zen koan, Donald Judd’s pencil plan made in 1977 for one of his stainless steel and green plexiglass sculptures had its own little betrayal of the human hand. There was a slight missed connection in the 90-degree angle at the corner that I relished, precisely because of its imperfection. My eighth-grade geometry teacher Mr. Voss would have punished Judd for the miscalculation, and some smart-ass with a CAD program would have corrected it in seconds on screen, but that is why the drawing is so wonderful.

The minimalists share a wall with a highly finished Gorky pencil drawing dated 1936. Here the artist uses generous crosshatching to build the volume of a convoluted central form, tucking the image of a bottle (or is it a bell?) in the upper left corner in a Surrealist ploy worthy of Magritte. The angled wings of the indeterminate space evoke a room or stage reminiscent of Picasso’s major still life paintings of the ’20s.

.

"Color(less)" at Van Doren Waxter. Courtesy of Van Doren Waxter.

.

The curators play the placement of this piece perfectly against the central, most chromatically arresting large work in the show, A Wall in Italy (1946) by Robert Motherwell. The tentacular black spokes of this piece made me think of Thomas Pynchon’s overweening fantasies, seemingly reaching out to the floating Gorky creature on the near wall. Texture and blunt force color--the Motherwell blacks arrive with a punch--take the show into a different dimension, through surrealism into abstract expressionism on paper.

I confess an uneasy disappointment with a pastel by Hedda Sterne, Horizon Study (1966), which seems pushed too hard. Sterne was the lone woman in the famous photo of the Irascibles, the definitive group portrait of the abstract expressionist movement, which appeared in The New York Times in 1951. Like the bright colors of the small Franz Kline oil on paper from 1954 with which it shares a wall, this is the contrapuntal moment in the show when color is allowed off the leash for a moment.

.

"Horizon Study" by Hedda Syerne, 1966. Oil pastel on paper, 19 x 14 inches. © The Hedda Sterne Foundation, Inc. / Licensed by ARS, New York, NY. Courtesy of Van Doren Waxter.

.

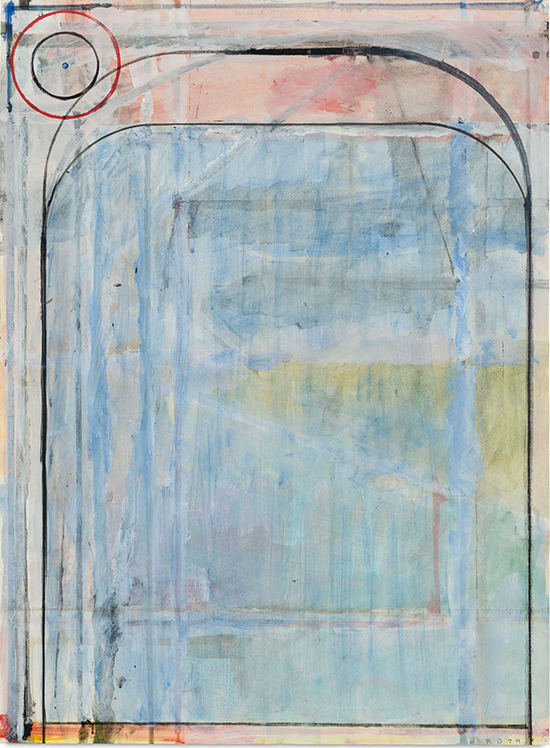

The chromatic highlight of the exhibition is a phenomenal gouache by Richard Diebenkorn dated 1979, replete with his signature pale blues in the wash technique that made him the Cezanne of Santa Monica. Elegantly contained in an arch-like curved form, it requires a sharper eye than mine to discern the ghostly black mullions of a grid behind the blues and golds.

.

"Untitled" by Richard Diebenkorn, 1979. Gouache and crayon on paper, 29 3/4 x 22 inches. Courtesy of Van Doren Waxter.

.

The thrill of a Mark Tobey tempera painting can only be experienced in the flesh--no reproduced image can convey it. The gem at Van Doren Waxter is Living Wall with Sign (1965), a lyrical burst of white writing within which a range of reds from crimson to scarlet to ruby emerge and sink, and flecks of purple and blue, dripped or flung, dot the surface. The boldest stroke is a calligraphic S in black, but even its opacity is illusory—the whites and reds behind the black can be read right through it.

Steps from the Van Doren show is the magisterial Frick Collection, where “Andrea del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action” is devoted to drawings and three paintings by Andrea d’Agnolo (1486–1530), known as del Sarto because his father was a tailor (sarto).

.

"Saint John the Baptist" by Andrea del Sarto (1486–1530), ca. 1523. Oil on panel, 37 x 26 3/4 inches. Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Florence By permission of the Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo.

.

"Study for the Head of Saint John the Baptist" by Andrea del Sarto (1486–1530), ca. 1523. Black chalk, 13 x 9 1/8 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Woodner Collection.

.

Hailed as “the faultless painter” by his pupil Giorgio Vasari, d’Agnolo was also celebrated in a splendid dramatic monologue by Robert Browning that keys on the sense of his effortless perfection, the sprezzatura of the virtuoso. With major loans from the Uffizzi, the British Museum, the Ashmolean, the Getty, the National Gallery in Washington, and other major institutions, this exhibition is a smaller version of a major monographic show that was at the Getty this summer.

.

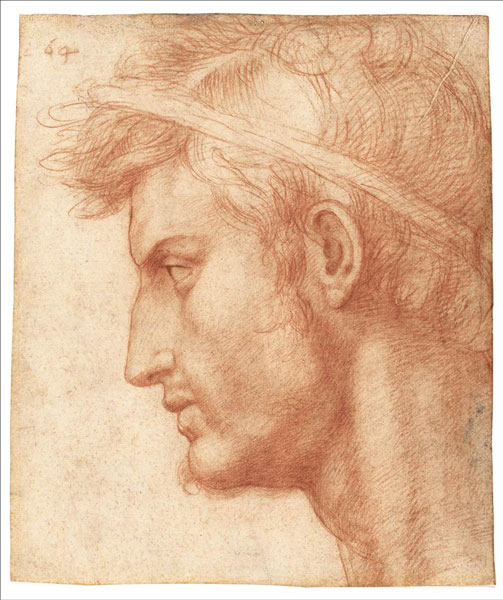

"Study for the Head of Julius Caesar" by Andrea del Sarto (1486–1530), ca. 1520. Red chalk, 8 7/16 x 7 1/4 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, partial and promised gift of Mr. and Mrs. David M. Tobey ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

.

Most of the drawings--including explosions of technical wizardry based on the complexities of the Laocoön and brilliant studies of young women and men in his busy studio in Florence--are in the dungeon of the Frick, but the paintings with related studies are in the oval room usually occupied by the Whistlers, and that is where there are lessons to be learned.

.

"Study of the Head of a Young Woman" by Andrea del Sarto (1486–1530), ca. 1523. Red chalk, 8 9/16 x 6 11/16 inches. Galleria degli Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Florence By permission of the Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo

.

Confronted by the mastery of d’Agnolo’s painting of the young man, which for centuries was taken to be a self-portrait, I turned to the drawings for hints at process. Like a coup de foudre, the little, fast sketches reveal a maestro struggling with his motif. With pentimenti and shifts, afterthoughts and corrections, a gauche and blocky forehead re-drawn over again three times, a densely worked then abandoned shoulder, the skirmish is anything but the evidence of a master breezing toward that final moment of perfection.

.

"Portrait of a Sculptor" by Andrea del Sarto (1486–1530).

.

Study for "Portrait of a Sculptor" by Andrea del Sarto (1486–1530).

.

Buried in his treatise on “The Work of Iron,” John Ruskin celebrated the importance of touch in art, an insight that embraces d’Agnolo as well as Rockburne, Diebenkorn, Tobey and all the intervening artists for whom drawing is essential.

As Ruskin wrote, “The utmost power of art can only be given in a material capable of receiving and retaining the influence of the subtlest touch of the human hand. That hand is the most perfect agent of material power existing in the universe, and its full subtlety can only be shown when the material it works on, or with, is entirely yielding. The chords of a perfect instrument will receive it, but not of an imperfect one; the softly bending point of the hair pencil, and soft melting of color, will receive it, but not even the chalk or pen point, still less the steel point, chisel or marble.”

___________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Andrea del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action” remains on view through January 10, 2016 at The Frick Collection, 1 East 70th Street, New York, NY 10021. 212-288-0700; www.frick.org.

"Color(less)" remains on view through December 23, 2015 at Van Doren Waxter, 23 East 73rd Street, New York, NY 10021. www.vandorenwaxter.com.

____________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.