“She had such beautiful hair,” Willem de Kooning said about the 20-year-old, Flatbush-born Elaine Marie Fried, the daughter of a German baker-turned-accountant for a bakery. Some 14 years his junior, she became de Kooning’s private pupil (pause here for knowing chortle) in the late fall of 1938. And that thick, reddish brown hair is a prominent feature in the absorbing and historically valuable exhibition “Elaine de Kooning Portrayed” organized by Helen Harrison, director of the Pollock-Krasner House, where it is on view through October 31, 2015.

.

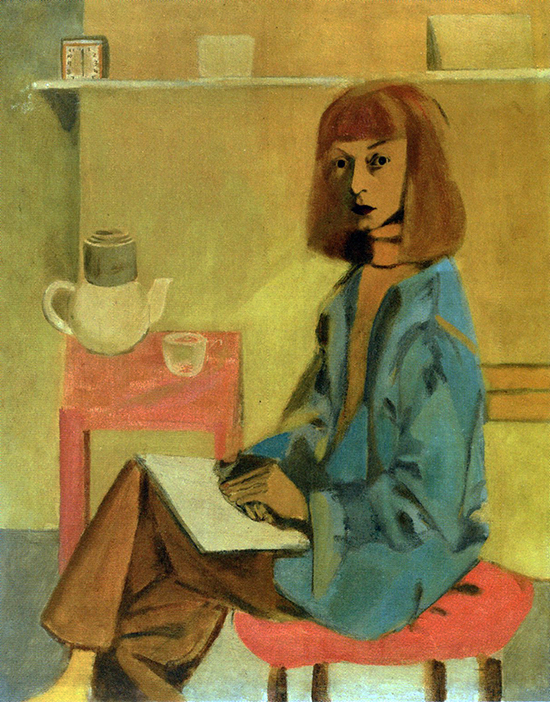

"Self Portrait" by Elaine de Kooning.

.

The most important wall, over the big circular dining table, is dominated by a group of self-portraits that Elaine made in 1946, when she still considered herself Bill’s pupil; the objects in the still life assignments he gave her are in the background of one of the painted portraits. They had married in 1943. Like the works in a concurrent exhibition of Elaine de Kooning’s work at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, these self-portraits glow with ambition bordering on assurance, even where the intensity of the gaze burns with effort into the mirror.

.

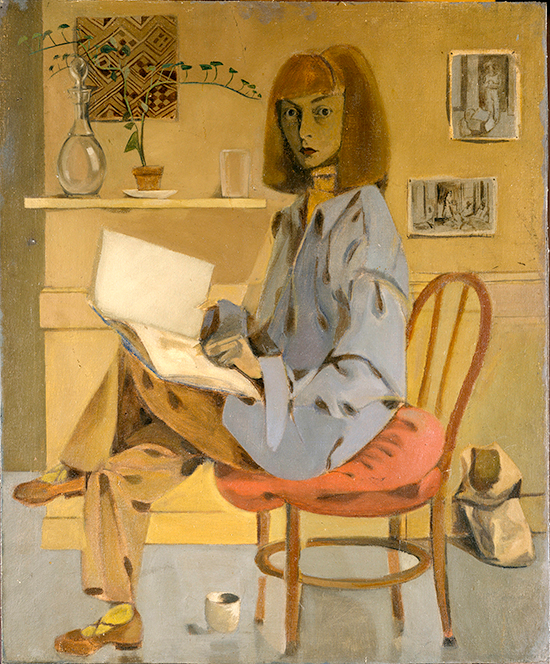

"Self Portrait" by Elaine de Kooning.

.

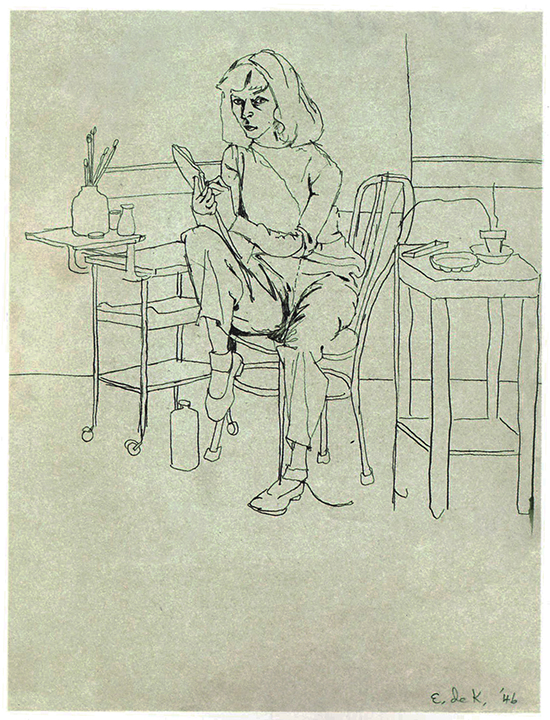

Legs crossed and head cocked in one of the pen drawings, she sits before the other three self-portraits, the lower left with lozenge-like shadows in the folds of her smock echoing the heavy notes in the painted portrait in which her hands rest folded on one another. The shadows are even denser in the version with a book (perhaps a sketchbook?) in her lap. The background and the angular chin, the crisp edges of her hair chopped in straight lines, the geometry of pant leg and cuff similarly lined: all reminded me of the stiffness in certain Balthus portraits from the same era.

.

"Self Portrait" by Elaine de Kooning.

.

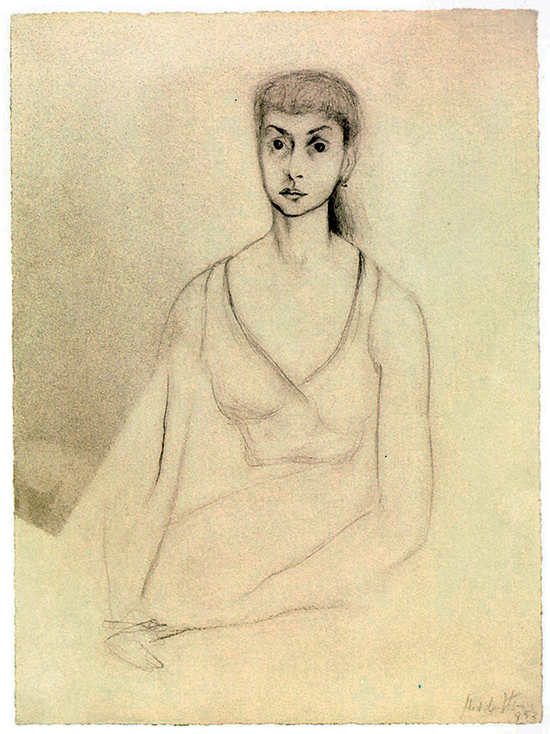

"Self Portrait" by Elaine de Kooning.

.

Is it fair to pitch husband against wife on this playing field? An awe-inspiring pencil drawing of Elaine by Bill is so technically superb that it intimidates. According to the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Willem de Kooning by Mark Stevens and Annalynn Swan, de Kooning was a reluctant portraitist but on the hunt for commissions nonetheless. A set of four round cameos published in the March 1940 issue of Harper’s Bazaar emphasizing hairstyles--as in this drawing of Elaine--look like bait.

.

Portrait of Elaine de Kooning by Willem de Kooning.

.

Meanwhile, broke and living in an apartment on East 22nd Street between Broadway and Fifth, not far from his loft on the same street near Seventh Avenue, Elaine was trying to score a modeling gig with the magazine as he was breaking into the commercial illustration circuit. Knowing the biographical back story helps the viewer peel back the layers of intention in the Willem de Kooning drawing at Pollock-Krasner House.

The biographers call the “Ingresque” drawing of Elaine the last he would make in “an academic, old-master style.” She is a waif wading in the folds of one of his old shirts, her hands meticulously realized. It was too tight for the tastes of Ashile Gorky, evidently, but it mesmerizes with its technical confidence, not just around the mouth and eyes but in the hands, apparently Bill’s favorite among her features. Everybody else seems to have been more drawn to her breasts (Gorky, Paul Harris) or eyes (Hedda Sterne, Alex Katz).

.

"Portrait of Elaine de Kooning" by Alex Katz, 1965.

.

An essential question was whether or not she was the “bitch goddess” in his controversial Women series that made its debut at the Sidney Janis Gallery in March 1953. At the party after the opening, Jackson Pollock yelled at de Kooning, “Bill, you betrayed it. You’re doing the figure, you’re still doing the same goddamn thing!”

To dispel the notion that she was the subject of the paintings (she used to say the series was based on her mother-in-law), she had Hans Namuth photograph her in front of them. “Take one of me in front of the painting to demonstrate, once and for all, that it has nothing to do with me,” she said. Then she backtracked as she saw that the hand of the painted Woman seemed to be resting on her shoulder in the photographs, almost as though she were the Woman’s daughter.

Sterne’s drawing of Elaine, made in 1953 a decade after they met, is all eyes--wide open and dilated and yet far off. They are not the dreamy, half-closed bedroom eyes on the cover of the slim but elegantly produced catalogue with its solidly researched essay by Phyllis Braff, a distinguished curator and critic for The New York Times as well as many other publications.

.

Portrait of Elaine de Kooning by Hedda Sterne.

.

The wide-awake look in Sterne’s drawing was part of Elaine’s persona, especially when it came to hitching her star to the wagon of an ascendant genius. Sterne related to Stevens and Swan, “She once told me that she married Bill because someone told her that he would be the greatest painter. But I didn’t believe her. She wasn’t that calculating.”

Gorky’s whisper of a pencil portrait was drawn in 1942, just about the period when he was a major part of their Chelsea existence, although his friendship with Bill went back to the ’30s. Her head is lifted upward, the bangs and chopped hair barely traced and there is a slight wobble in the line about the eyes that indicates indecision. The swift and expressive touch makes a telling comparison with the firm anatomy of Bill’s drawing from a year before.

The precise opposite of that tentative sense of hesitation characterizes the paintings of both Alex Katz and Fairfield Porter, who imbue their subject with color-suffused boldness from the warm side of the palette, specifically reds more suited to Elizabeth Arden and Christian Louboutin than the painting studio. The raised right eyebrow in the Porter portrait suggests impatience.

.

Portrait of Elaine de Kooning by Fairfield Porter.

.

From their first meeting in 1960, Elaine and Katz painted each other, and showed together at the Tanager Gallery. The Katz portrait from 1965 has a sadness about the eyes that can also be seen in the drawing by her friend Aristodimos Kallis.

Color is the key to Pauyl Harris’s Elaine Remembered, a crayon on paper abstract work that associates certain tones with a particular episode in her life: the summer of 1949 in Provincetown when the sky shone blue. The peachy tones, according to the all-knowing Helen Harrison, connoted her sweetness.

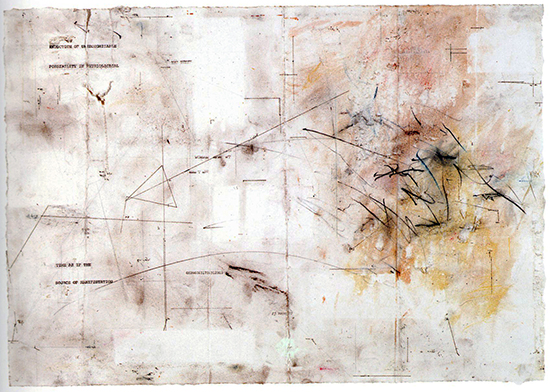

It may be the oddest visual work in the show, but Edvard Lieber’s Point: Elaine de Kooning Sketching in Central Park is probably the most intimate in many ways. Lieber is a painter, composer, concert pianist, filmmaker and the executor of the de Kooning estate, having been an assistant to Elaine from 1979 until her death in 1987. The drawing, which has the delicate smudges of color of a John Cage work on paper, offers a counterpoint between brief typed phrases (“Source of Manifestation” and “Time as if the”) and the straight-edged silhouettes of photographs that he made of her one day in Central Park, first mounted on the paper and then removed.

.

"Point: Elaine de Kooning Sketching in Central Park" by Edvard Lieber.

.

Lieber’s musical compositions inspired by Willem de Kooning’s paintings led him to the studio, and the drawing feels like a score for an avant-garde piece. Braff’s essay wonderfully invokes the too-often abused word “aura” to describe the play of presence and memory in the work.

Intimacy is the coin of the realm in portraiture, and nothing could be more valuable than this insider’s composite portrait of one of the great artist-muses of our time hung by an expert insider (Harrison) in the rooms not far from Elaine de Kooning’s own home on Accabonac Creek, where her peals of laughter and Brooklyn accent still echo.

___________________________________

BASIC FACTS: "Elaine de Kooning Portrayed" remains on view through October 31, 2015. Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center is located at 830 Springs Fireplace Road, East Hampton, NY 11937. www.pkhouse.org.

___________________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.