Miriam Schapiro, an internationally acclaimed painter, sculptor and printmaker who was at the forefront of the feminist art movement in the 1970s, died at the home of her caregiver in Hampton Bays on Saturday, June 20.

The artist, who spent many years on Long Island’s East End and was also known as one of the founders of the Pattern and Decoration movement, was 91.

.

Miriam Schapiro, 2002.

Photographer: Anne Burlock Lawver, Richmond, Virginia; Institution: Miriam Schapiro. Courtesy of jwa.org.

.

Contacted for comment last week, Christina Mossaides Strassfield, museum director and chief curator at East Hampton’s Guild Hall Museum, offered high praise for Schapiro and her accomplishments.

“Miriam Schapiro was an artist who contributed so much to empowering women,” Strassfield wrote in an email. “Miriam was a leader and innovator and was a champion for bringing attention to women artists. I had the honor of curating an exhibition of her work at Guild Hall in 1992, ‘Miriam Schapiro: The Politics of the Decorative,’ which allowed me the opportunity to get to know her better.”

“She was feisty and opinionated,” Strassfield wrote, “but she earned the right to be both! I loved the way she was always willing to keep her work fresh and current. At one time she and her husband, Paul Brach, were the ‘Art Star’ couple.”

Alicia Longwell, the Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Chief Curator, Art and Education, at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, describes herself as “a friend and admirer” of the late artist.

“Miriam Schapiro was a powerhouse of talent, enthusiasm, and sheer determination,” Longwell wrote in an email. “In the late 1960s she was transplanted to the West Coast, where her husband, the artist Paul Brach, became dean of the art department at the California Institute of the Arts. It was a move that radicalized her thinking and her art.”

“Her highly individual response to the women’s movement,” Longwell wrote, “took the form of dazzling collages of fabric, ribbon, and lace, infusing traditional feminine materials with power and authority.”

“Mimi, as everyone called her, and Paul were vital members of the East End artists’ colony, spending their first summer here in the 1950s when they were invited to stay with the dealer Leo Castelli in Georgica. They built their own home some years later in Wainscott, a legendary gathering place for artists, neighbors, and friends.”

Schapiro was one of the few women in the second generation of Abstract Expressionists in the late 1950s. As Longwell noted, she embraced feminism in the early 1970s after her move to California and made it the cornerstone of her work going forward.

As William Grimes wrote in an obituary in The New York Times, she dedicated herself to “redefining the role of women in the arts and elevating the status of pattern, craft and the anonymous handiwork of women in the domestic sphere.”

.

"Children of Paradise" by Miriam Schapiro, 1984. Collage and print, 48 x 32 inches. Photo courtesy of Guild Hall.

.

In 1970, Schapiro and the artist Judy Chicago founded the Feminist Art Program at the newly created California Institute of the Arts. The program had as its mission the creation of a new understanding of art based on women’s history and social experience.

As part of this mission, she and Chicago, along with 21 students and a number of local artists took over a decaying mansion in Hollywood to create “Womanhouse.” Opening in January 1972, the installation dramatizing the American home as a prison for women and their dreams drew huge numbers of visitors and national attention.

Moving on from “Womanhouse,” Schapiro began using decorative pieces of fabric, and later entire handkerchiefs and aprons, in acrylic paintings she called “femmages.” The intent, as Grimes pointed out in the Times obituary, was “to honor the silent centuries-old work of women engaged in humble tasks like sewing and knitting, or, as she put in a 1977 interview, ‘to choose something considered trivial in the culture and transform it into a heroic form.’”

In the mid-1970s, she and Robert Zakanitch joined with Joyce Kozloff, Robert Kushner, Valerie Jaudon, and other artists in what they called the Pattern and Decoration movement. With feminism at its core, the movement dismissed the austerity of Minimalism and Conceptual Art in order to incorporate decorative elements from such sources as Amish quilts, Islamic tile work and wallpaper.

.

"Heartland" by Miriam Shapiro, 1985. Collection of Orlando Museum of Art. Courtesy of ArtNet.com.

.

The goal was of the movement was to break down traditional boundaries between high art and craft and to offer validation for the decorative pattern work that women had applied to ceramics and textiles throughout the ages.

Born in Toronto in 1923, Schapiro grew up in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn. She graduated from Erasmus Hall High School and enrolled in Hunter College but later transferred to the University of Iowa, where she studied under the printmaker Mauricio Lasansky. She earned a bachelor’s degree in graphic art and a master’s in printmaking before receiving her master’s in fine art in 1949.

It was at the University of Iowa that she met and married a fellow art student, Paul Brach. The couple moved in the early 1950s to New York, where Schapiro exhibited large paintings that included landscape and portrait elements in the 1957 installment of the “New Talent” shows at the Museum of Modern Art. Her first solo show was at the André Emmerich gallery in 1958.

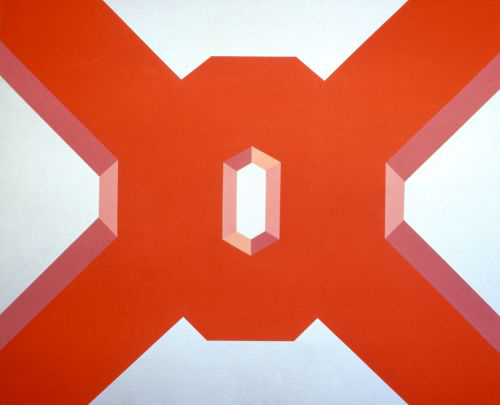

Schapiro’s looser expressionist paintings crowded with brushwork at the start of her career began to include, along with images evoking the feminine, geometric forms and more open spaces in the 1960s. She would go on to embrace hard-edged abstraction in the same decade. As Grimes noted, the female egg mutated into the vaginal O of Big Ox (1968), a severely geometric form with four “limbs” extending powerfully from an open octagon.

.

"Big Ox No. 2" by Miriam Shapiro, 1968. Acrylic on canvas. Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, Gift of Harry Kahn. © Miriam Schapiro.

.

In the 1980s, Schapiro drew on dance for her subject matter. According to the Times obituary, she later went on to create a series of paintings that “engaged female artists of the past, notably Frida Kahlo, the focus of several works with mythic overtones.” In 1999, she painted the monumental “Diva” to honor the black contralto and civil rights heroine Marian Anderson.

The artist’s work was the subject of several traveling retrospectives. During the course of her career, she wrote two books, Women and the Creative Process (1974) and Rondo: An Artist’s Book (1988).

Predeceased by her husband, Paul Brach, in 2007, she is survived by a son, Peter von Brandenburg.

__________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.