In a bold stroke, the Nova Southeastern University (NSU) Museum of Art (MOAFL) in Ft. Lauderdale presents an object lesson in how the influence of a Danish artist, who worked in the latter half of the 19th century, can still be seen in the work of one of the more successful artists of the second half of the 20th and into the 21st.

The Danish artist is the slightly known expressionist J.F. Willumsen (1863-1958) and the exhibition is “Café Dolly: Picabia, Schabel and Willumsen”, on view at MOAFL through February 1. Mixed in with the works of Willumsen are rarely seen works by the better known Dadaist Francis Picabia (1879–1953) and newer work by the suddenly resurgent Julian Schnabel (b. 1951), who—as might be expected—is the main draw.

.

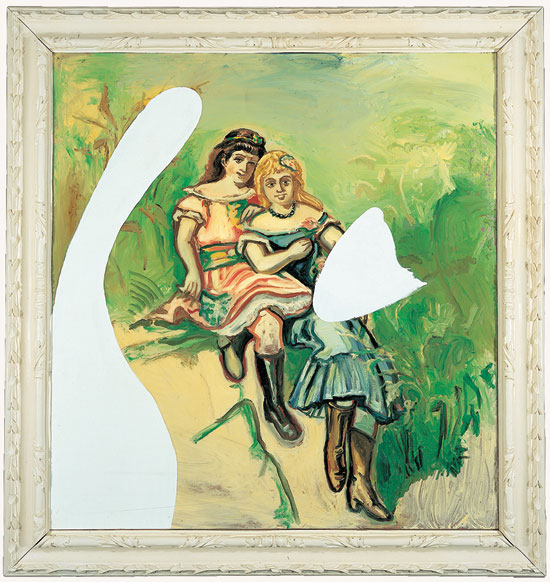

"Las Niňas" by Julian Schnabel, 1997. Oil, resin, and enamel on canvas. Collection of the artist. © 2014 Julian Schnabel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

And while Schnabel is certainly the main event for this odd “Café Dolly” hybrid, once one stands there, as I did in December, the exhibit is such a visual feast it’s unclear who’s piggy-backing on whom. The show and accompanying catalogue are well conceived, perfectly executed, and a manifest pleasure to explore. It is Willumsen who ends up the star here, as I repeatedly mistook paintings by him for works by Schnabel, except a hundred years earlier.

.

"The Festival of Redentore in Venice, Palazzo Balbi on Canal" by J.F. Willumsen, 1929. Oil on canvas. J.F. Willumsens Museum. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / billedkunst.dk.

.

The MOAFL show expands on an exhibition originally organized by the J.F. Willumsen Museum in Frederikssund, Denmark, to feature its namesake’s work on the occasion of his 150th birthday.

The exhibition title, “Café Dolly,” could be taken as a reference to the popular pub Café Dolly in Horsens, Denmark, about 20 miles from the Willumsen museum, www.cafedolly.dk. According to a MOAFL spokesperson, the exhibition title references the first cloned sheep, mischievously named Dolly after Dolly Parton, as it was cloned from a mammary cell. Dolly's birth in 1996 (the cloned sheep) sparked international controversy and called into question cultural ideas about ethics and materiality.

In a visual arts context, Picabia, Schnabel, and Willumsen challenge the same concepts in their unprejudiced treatment of the traditions of art history and mass media images as well as private photographs and stories.” But, given that the exhibition originated in Denmark as a one-person show of Willumsen’s work and the “café” in the title lands it squarely on a local establishment of the same name, the pub connection cannot be ignored.

That’s one of the great things about art: everyone gets to decide for themselves, about everything. My bet is on the beer-goggles.

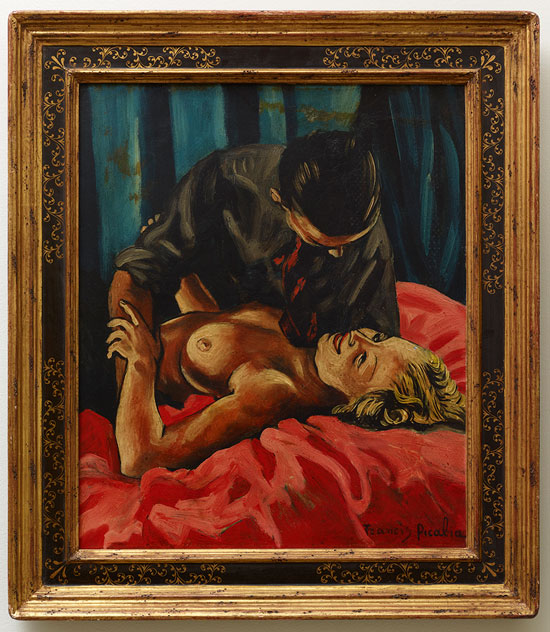

Parisian Francis Picabia was one of the leading figures of Dada and later Surrealism. Starting around 1915 he was one of the main leaders of the Dada movement and wrote many of its manifestos, but he switched to figuration in the 1920s. By World War II he was using themes from erotic magazines and popular culture and was therefore deemed regressive by his fellow Dadaists, who essentially booted him out of the club.

.

"L'Etreinte" by Francis Picabia, 1940-44. Oil on canvas. Private collection, Denmark. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

.

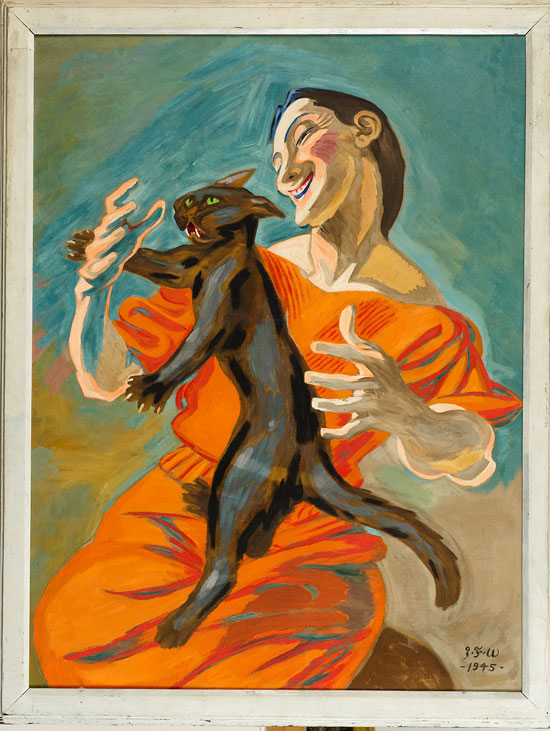

J.F. Willumsen (1863-1958) worked for more than seven decades. Although he was a bit older, he was a contemporary of Picabia and a co-founder of the association, Den Frie Udstilling (The Independent Exhibition) in Copenhagen in 1891. Living for most of his life in France, Willumsen developed a powerfully personal style regarded alternately as symbolist or kitsch, which did not favor him at the time but seems mainstream in the 21st century.

.

"Woman Playing with a Black Cat" by J.F. Willumsen, 1945. Oil on canvas. J.F. Willumsen Museum. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / billedkunst.dk.

.

The original “Café Dolly” show was curated by visual artists Claus Carstensen and Christian Vind, who felt Willumsen wasn’t getting his due, with research by Ann Gregersen of the University of Copenhagen.

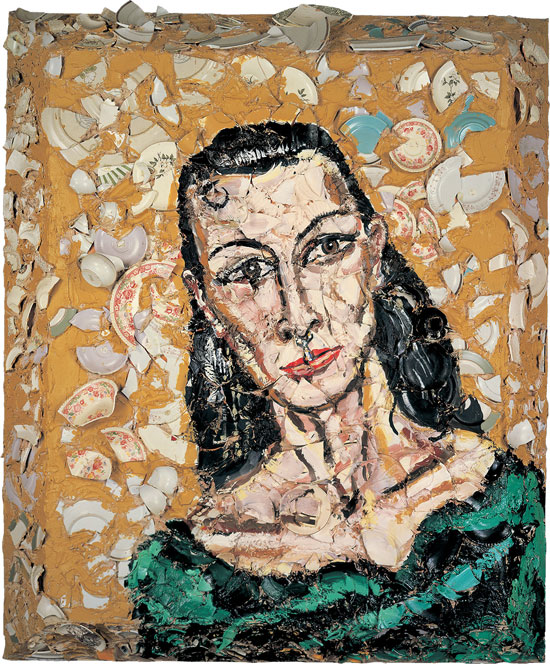

Bonnie Clearwater, the Director and Chief Curator for the NSU Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale (MOAFL), was clever enough first to adopt this show and then to add work by Julian Schnabel and Francis Picabia in the Fort Lauderdale version. Schnabel is enjoying a suddenly resurgent painting career that has the New York critics retyping their profile of him for yet a fourth time.

.

"Portrait of Alba Clemente" by Julian Schnabel, 1987. Oil, plates, and bondo on wood. Private collection, New York. © 2014 Julian Schnabel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

There is a harmony of color and composition in the work of these three artists, so much so that without checking the labels I picked the artist wrong about a third of the time. It is well-known that Schnabel’s work has often been sourced in that of Picabia, but I have found no mention that Picabia poached off Willumsen, who was 16 years his senior and lived in Paris at the same time.

Willumsen’s The Birthday Cake. A Joke, 1943, was painted during the maelstrom of WWII when Paris was under Vichy rule, but there is nothing of that time included in the painting’s nutty imagery: a slender woman with muscled arms and angel wings serving a cake with four candles to someone out of the frame. Unless, of course, it is painted from the viewpoint of a 4-year-old, then it begins to make sense: mother is tall and angelic and can hoist the tot off the floor at will.

.

"The Birthday Cake, A Joke" by J.F. Willumsen, 1943. Oil on canvas. J.F. Willumsen Museum. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / billedkunst.dk.

.

However, the date on the cake betrays the subject; it is a skewed image of Willumsen’s muse and mistress Michelle Bourret on the occasion of Willumsen’s 80th birthday. At 80 perhaps the artist could be forgiven for not caring which army marched outside his window, opting instead to focus on his playful relationship with his main squeeze.

There is something special about this work, even great, and the staff was correct to use it as the cover of the book that accompanies the show.

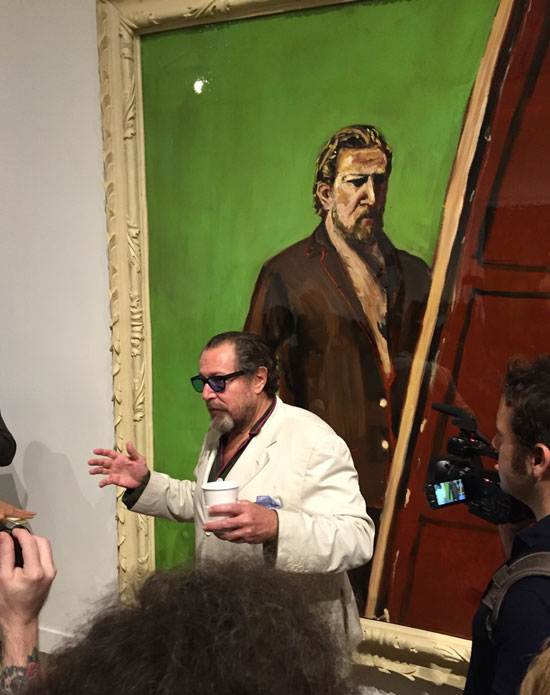

At the press briefing I attended during the week of Art Basel Miami Beach, Schnabel made an amusing appearance, showing up in pajamas worn under a Gaultier sport coat with a pocket-handkerchief folded poofy-poof. In combination with blue glasses and some grungy, untied deck shoes, this made for the sort of entrance that writers have come to expect from Schnabel.

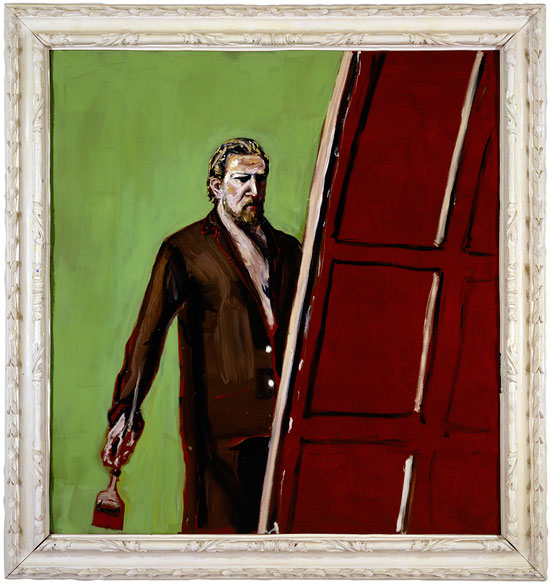

The pajamas were the same ones he wore when he painted Untitled (Self-Portrait), 2004, and he posed beneath the work for the cameras. Unfortunately, it’s the least interesting painting in the group; by 2004 he was on to a stellar career in movie directing, so perhaps his attention was elsewhere.

.

"Untitled (Self-Portrait)" by Julian Schnabel, 2004. Oil and resin on canvas. Private collection. © 2014 Julian Schnabel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

Under his sport coat, artist Julian Schnabel wore the same pajamas to the MOAFL event in December that he was wearing when he painted "Untitled (Self Portrait)." Photo by James Croak.

.

Schnabel’s best painting in this show is one that came by chance: the artist found a clumsy portrait of a young blond girl in a thrift store and dabbed a black gash across her eyes, bringing an odd mystery to a bland subject. Large Girl with No Eyes, 2001, is an enlarged version of this found object piece, and is one of Schnabel’s better works.

.

"Large Girl with No Eyes" by Julian Schnabel, 2001. Oil and wax on canvas, collection of the artist. © 2014 Julian Schnabel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

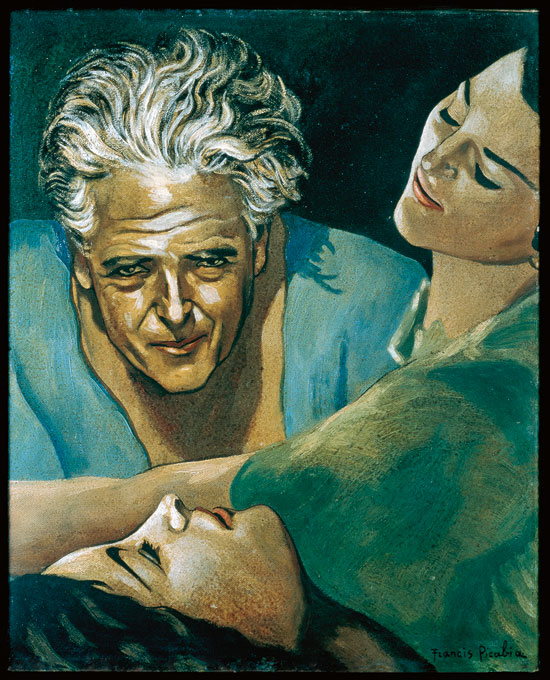

One of Picabia’s seminal works is also included in the show, the rarely seen but often published Autoportrait, ca. 1940-42. Like some of Willumsen’s work, it was painted during the Vichy regime in occupied Paris but shows the artist partying with two women like it was 1939. Similar to Willumsen’s Birthday Cake, it has nothing to do with the disorienting surroundings of the time and makes one wonder about the worldview of these two artists who lived through it.

.

"Autoportrait" by Francis Picabia, 1940-42. Oil on cardboard. Lucien Bilinelli Collection, Brussels/Milan. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

.

Overall, this raucous and satisfying exhibition, along with the others on view, should be high on anyone’s list for shows to attend.

The Nova Southeastern museum that houses the exhibition is a prodigious structure occupying a two-story modernist building of blanched volumes constructed at oblique angles. The good architecture and the two sophisticated shows—the second show running concurrently is a photography survey from the collection of Martin Z. Margulies—offered the impression of a budget and staff normally beyond the reach of a college.

BASIC INFO: “Café Dolly: Picabia, Schnabel, Willumsen” remains on view through February 1, 2015 at the Nova Southeastern University Museum of Art (MOAFL), 1 East Las Olas Blvd., Fort Lauderdale, FL, www.moafl.org.

An illustrated catalogue titled “Café Dolly: Picabia, Schnabel, Willumsen, Hybrid Painting,” published by Hatje Cantz, accompanies the exhibition and is available at the NSU Museum of Art store. It features essays by Margrit Brehm, Claus H. Carstensen, Anne Gregersen, Annette Johansen, Roberto Ohrt, and Christian Vind.

Also on view is “American Scene Photography: Martin Z. Margulies Collection” through March 22, 2015 and “Highlights from the William J. Glackens Collection” through February 2015. On long-term view is the installation The Indigo Room or Is Memory Water Soluble by Edouard Duval-Carrié.

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.