An eye-opening show, “Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art” presents a game-changing look at what it means, in this second decade of the 21st century, to be an American artist with Latin American ancestry. On view at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum of Florida International University, the works selected for the exhibition are drawn entirely from the Smithsonian American Art Museum collection.

With shades of multi-cultural debates from the 1980s and ’90s, this show asks viewers to ponder these questions: Whose America? And who is making art history currently in this country? Don’t even think of expecting a concise reply. The answers are always changing as Latino artists themselves evolve in response to the ever changing “Our America” shared by artists living and working in this country from sea to shining sea. Scholarship regarding these artists is evolving, too.

The Smithsonian’s Latino art curator E. Carmen Ramos brings much insight to this exhibit, which charts the relatively brief and upstart history of Latino art, acknowledging its deep roots in U.S. history, particularly in the Southwest. Bringing together 85 works in all media by 64 artists, it shows how the ever widening mainstream of Made in America art is becoming more diverse, engaging, and downright intriguing before our very eyes.

Latinos: Largest Ethnic Group in United States

In an age when ugly debates about race, immigration and the “value” of higher education and cultural institutions seem more polarizing than ever, the numbers don’t lie. The very idea of what constitutes “Our America” is undergoing a radical shift. As Tomas Ybarra-Frausto explains in his catalog essay, “In the twenty-first century a demographic transition in American society positions Latinos as the largest ethnic group in the country. Yet for many Americans, Latinos remain like shadowy ciphers, notably absent from narratives of American art.” With admirable activism, “Our America” broadens those narratives.

Latinos include native-born citizens and immigrants from more than 20 countries in the Caribbean and Central and South America. Generally, concepts about Latino communities seemed to gel in the years following World War II, as Latinos began challenging their marginalized position vis a vis civil rights, education, and culture.

This exhibit focuses on art created by the three largest Latino communities in the United States: Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans. The Frost exhibit is enriched by art by Cuban Americans with strong ties to Miami, including María Brito, Teresita Fernández, María Martínez-Cañas, Arturo Rodríguez, and Rafael Soriano.

Abstraction, Rhythmic and Elegant

Notable works of abstract art by Latinos have been omitted from familiar discussions that include such well-known artists as Stuart Davis and Robert Motherwell. In the 1970s, when Caribbean immigrants to New York popularized infectious salsa rhythms thanks to such musicians as Johnny Pacheco, Freddy Rodríguez created dynamic abstractions edged sharply with what might be called salsa’s “island beat.” Influenced by dance music from Cuba and Puerto Rico, salsa incorporates Afro-Cuban rhythms and American echoes of the Hustle. To some extent, salsa mirrors the intermingling creative spirit of “Our America.”

Another abstract artist highlighted here is Carmen Herrera, known for her elegant take on minimal geometric forms. Born in Cuba in 1915, she studied painting and sculpture in Havana and Paris before moving to New York City in 1939. Her hard-edge canvases display an acute sense of color and space, evoking three dimensions. Many see conceptual links between her art and that of pioneering Brazilian Lygia Clark (1920-1988). Additionally, scholars maintain that Herrera’s art anticipates later developments in minimalist painting and sculpture.

Somewhat younger than Herrera, Olga Albizu first encountered gestural abstraction in Puerto Rico in the 1940s, when studying with exiled Spanish artist Esteban Vicente. Later in that decade, both had moved to New York and were active among groups of abstract artists. Her progressive, vibrant use of color was surely nourished by studies with Hans Hoffmann. Included in an exhibit at New York’s Pan American Union, her art sparked the attention of financier and art collector David Rockefeller, who was building Chase Manhattan Bank’s modern art collection. Chase purchased Radiante (1967) two years after it was painted; later it was gifted to the Smithsonian by JPMorgan Chase.

.

"Radiante" by Olga Albizu, 1967. Oil on canvas, 68 x 62 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of JP Morgan Chase.

.

Radiante gleams with the sunshine of high noon, even as it challenges the eye with Hoffmann’s influential “push-pull” ideas about spatial form and color. There’s a lively, almost jazzy rhythm to the way Albizu applied thick splashes of yellow, orange and black paint to the canvas.

The City as Canvas

Certainly urban settings, from Los Angeles to New York City, proved fertile inspiration for many Latino artists, who made the city their own canvas. Murals have been especially popular in Mexican American communities, given the prominence of 20th Century Mexican muralists Orozco, Rivera, and Siqueiros. By the 1970s, murals depicting barrio life and often agitating for social change were appearing in housing projects and on storefronts in Puerto Rican and Chicano communities. The murals reflected an America roiled by 1960s controversies over civil rights, campus protests, the Vietnam War and Cuban Revolution.

Cool, clean compositions of Emilio Sánchez, such as Untitled, Bronx Storefront, “La Rumba Supermarket” (late 1980s), reveal his abiding interest in the dramatic interplay between light and shadow, creating abstract geometric patterns. The pared-down simplicity of his city scenes carries reminders of both Edward Hopper and the surreal settings of de Chirico. Moving to “Our America” in the 1940s, Sánchez considered himself a New Yorker from Camaguëy, Cuba.

.

"Untitled, Bronx Storefront, 'La Rumba Supermarket,'" by Emilio Sánchez, Late 1980s. Watercolor on paper. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the Emilio Sánchez Foundation. © Emilio Sánchez Foundation.

.

Sixteen years after the mysterious death in 1970 of award-winning Chicano journalist Rubén Salazar in Los Angeles sparked outrage, Frank Romero painted Death of Rubén Salazar (1986). Depicting an assault by police officers on a barrio bar where Salazar had stopped by, Romero paints with an almost gleefully cartoonish manner that simultaneously belies and underscores the event’s tragic significance. Here, the punch of street art style deplores the silencing of a voice that chronicled the growing Chicano civil rights movement.

.

"Death of Rubén Salazar" by Frank Romero, 1986. Oil on Canvas, 72 ¼ x 120 3/8 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum Museum purchase made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment. © 1986, Frank Romero.

.

Domestic Objects and Settings Transformed

Claes Oldenburg’s 1960s soft sculptures of ordinary objects are Pop art icons. Some 50 years later, Margarita Cabrera also makes soft sculpture, but updated with wry awareness of poor working conditions in factories, in Mexico and elsewhere, supplying the U.S. market. Her Brown Blender (2011) lacks Oldenburg’s amused mockery of American obsession with consumer goods. Instead, it’s messy and mocks the slickness of mass-produced objects with a vulnerable, hand-made appearance.

.

"Brown Blender" by Margarita Cabrera, 2011. Vinyl, copper wire and thread. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Museum purchase through the Luisita L. And Franz H. Denghausen Endowment. © 2011, Margarita Cabrera.

.

Often incorporating elements from domestic interiors, elaborate installations by Maria Bríto have been compared to those by Joseph Beuys and Doris Salcedo. Her El Patio de Mi Casa (1990) is typically redolent with familiar objects, like a kitchen sink and bed. They’re poetically suffused with references to her experiences as a Cuban exile uprooted as a girl before forging a new identity as a strong-minded woman in Miami.

.

"El Patio de Mi Casa" by María Brito, 1990. Mixed media including acrylic paint, wood, latex, gelatin silver prints and found objects, 95 ½ x 68 ¼ x 65 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquisition Program, 1997.1A-G. © 1991, María Brito.

.

Portraying Diaspora

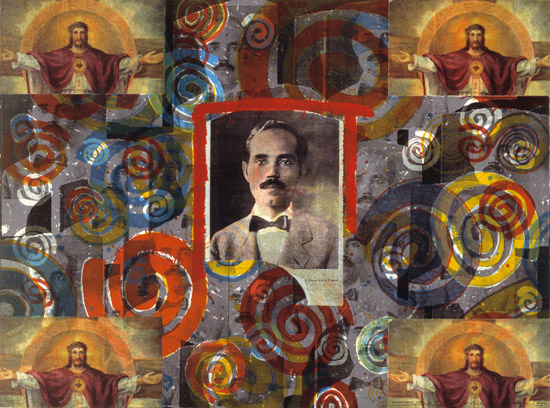

Since the 1980s, Juan Sánchez has explored the bittersweet challenges of living in the Puerto Rican diaspora, layered with memories good and bad. Such layering characterizes his lithograph and collage Para Don Pedro (1992). Catholic iconography mingles with allusions to Puerto Rican history and indigenous petroglyphs, spurring reflections on colonialism’s living legacy.

.

"Para Don Pedro" by Juan Sánchez, 1992. Lithograph, photolithograph and collage with additions in oil stick and pencil, 22 ¼ x 30 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Julia D. Strong Endowment. 1998.97. © 1992, Juan Sánchez.

.

For decades, the United States has intervened repeatedly in Latin American politics, prompting journalist Juan Gonzalez to dub Latinos the “Harvest of Empire” in his book of the same title. Thanks in large measure to Latino artists, that harvest is finally yielding fruit worthy of “Our America.”

BASIC INFO: “Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art” remains on view through June 22, 2014 at the Frost Art Museum, 10975 SW 17 St., Miami, FL 33199. For details, visit www.thefrost.fiu.edu.

_______________________________

Copyright 2014 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.