The building may be familiar, but the surprises in store when the new Met Breuer—in the former home of the Whitney Museum—opens to the public on March 18, 2016 have already rattled even some of the most jaded art connoisseurs.

Most entered the press preview on Tuesday, March 1, 2016 with expectations of some kind of throwback to the cutting-edge experiences they had endured in the same space, perhaps a Metropolitan Museum version of the Whitney Biennial shock therapy. Then the massive elevator doors opened on Titian’s epic Marsyas, along with other huge Renaissance paintings by Leonardo, van Eyck and Rembrandt, and jaws dropped at the head fake the Met’s curators had put on them.

.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Copyright 2016.

.

"The Flaying of Marsyas" by Titian, c. 1570s. Oil on canvas, 86 5⁄8 × 80 1⁄4 inches. Archdiocese Olomouc, Archiepiscopal Palace, Picture Gallery, Kromĕříž.

.

In fact, the superb opening exhibition of 190 works addresses one of the deepest questions in aesthetics, the problem of “Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible.” While the Titian is signed, curators suggest that near his death Titian left parts of it unfinished (an invitation to stall and look closely). Other works in the show are intentionally unfinished, and a few are arguably outside the pale but pose a fascinating question of whether or not paintings are ever finished (think: Jackson Pollock) in their essays into infinitude.

As a bridge from the Met’s historical strengths as a repository of masterpieces to the contingent ideology of Modernism, the exhibition represents a strategic coup. The show dramatically teaches that when the boundaries are blurred between the study for a work and the thing itself, the viewer can have a sense of entering into the process.

Tucked into a corner even though he might have been more central, Manet was one of the key figures in the understanding that it is not just a work of art but even a masterpiece that can be unfinished. In Florence, Rodin learned from looking at Michelangelo that a portion of his sculpture could be left as raw stone for an expressive heart punch, as a sunlit gallery of his sculpture along with those of Medardo Rosso attest.

.

"The Hand of God" by Auguste Rodin, Modeled ca. 1896–1902, commissioned 1906, carved ca. 1907. Marble, 29 × 23 × 25 1⁄4 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Edward D. Adams, 1908.

.

From the Renaissance and Baroque to the Modern period, the non-finito gained status in the judgment of art. This shift is most wonderfully shown on the fourth floor through a savvy selection of paintings by Picasso, notably his portraits of his first wife Olga made in 1919. The top half of one, painted on paper, has a degree of realism that owes a debt to Ingres, his historic rival, while the bottom is a free drawing in charcoal that takes over and spins its line joyously, black on white.

The best wall in the show is dedicated to a juxtaposition of Cezanne and Picasso, both of whom unabashedly left the white of the canvas to the viewer’s imagination. When he made these paintings, Picasso had escaped the cul-de-sac of Cubism into his own brand of theatrically inspired realism. The Ballets Russes had waltzed the genius away from Montparnasse to Neoclassicism, but with the twist of the unfinished keeping it grounded in the 20th century.

.

"Gardanne" by Paul Cézanne, 1885–1886. Oil on canvas, 31 1/2 x 25 1/4 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Franz H. Hirschland, 1957.

.

Traffic patterns in the galleries during the press preview were revealing, as everybody flocked to the paintings. The inner rooms of the formidable exhibition of Nasreen Mohamedi during the press preview were deserted, as only a few curious souls explored the quiet monochromes in pencil and ink from the 1960s in the first couple of galleries.

.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Copyright 2016.

.

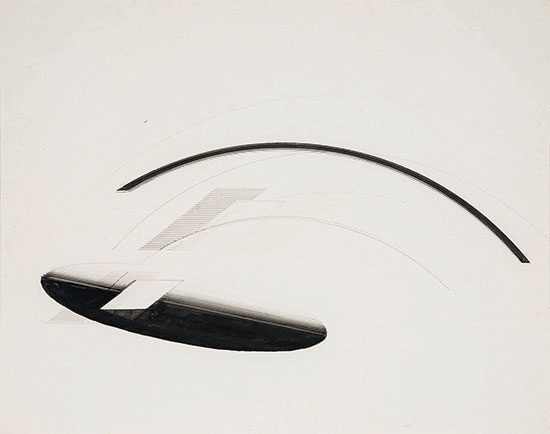

"Untitled" by Nasreen Mohamedi, c. 1980. Ink and graphite on paper, 10 1/2 × 13 1/2 inches. Collection of Dossal Family (Mariam Panjwani, Zeenat Sadikot, Laila Khalid).

.

The “graphic minimalism” of Mohamedi, hardly a celebrity in the brand-conscious world of Contemporary art, was a brave choice for the start of an exhibition program at a museum that has never been perceived as a powerhouse in the period.

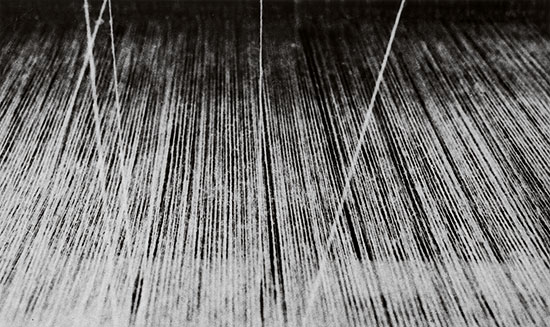

Sheena Wagstaff, Leonard A. Lauder Chairman of the Met’s Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, explained in a press release: “One of our goals with The Met Breuer is to present thoughtful exhibitions that posit a broader meaning of modernism across vast geographies of art. The poignant story of Mohamedi, a relatively little-known but significant artist, reveals a highly individual artistic quest, drawing on historic sources from across the world, alongside her evocative photography as an unexpected form of visual note-taking.”

.

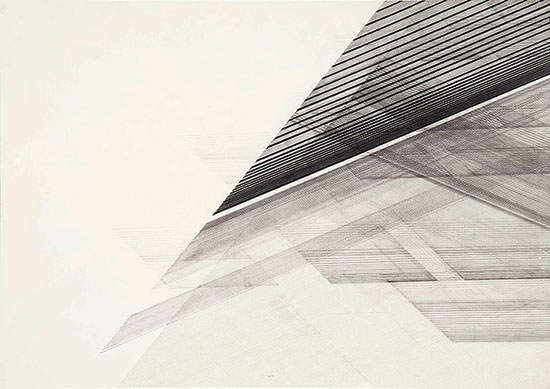

"Untitled" by Nasreen Mohamedi, c. 1975. Ink and graphite on paper, 20 × 28 inches. Sikander and Hydari Collection.

.

This large and meticulous show of more than 130 works, covering Mohamedi’s entire career from the 1960s up to her death in 1990, is the first museum retrospective of the artist’s work in the United States. It has transnational partners in the MuseoNacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid and the KiranNadar Museum of Art in New Delhi.

The dominant mode is a weave of light and shade through grids that have been painstakingly built with pencil and ink lines. The key to the show, for this writer, was a small sketchbook that interposes text with blacked out bands of ink across the spreads, a deeply personal glimpse of the delicate intellect at work.

Even the photographs and certainly the compact, flowing drawings, which stretched grids into diagonals and vortices, give what can be a static format the kinetic life that makes it human. It is a sophisticated group of works, reflecting an interdisciplinary and international mind.

.

"Untitled" by Nasreen Mohamedi, c. 1970. Black-and-white photograph, Printed in 2003, Edition 10 of 10, 8 5/8 × 14 1/2 inches. (C) Estate of Nasreen Mohamedi / Courtesy Talwar Gallery, New York / New Delhi.

.

Mohamedi—who was born in 1937 in Karachi (then British India, now Pakistan), moved to Bombay (now Mumbai) and studied at Central Saint Martin’s in London—had an international range of stimuli. She traveled from Bahrain, where her father was a businessman, to Paris, Tokyo and New York. Her reading blends Sufi poetry with Rilke, Camus, and Mohammad Iqbal, while her visual vocabulary certainly included Agnes Martin, to whom she is often compared, and the Minimalists.

Mohamedi’s firm sense of geometry accorded well with the iconic Breuer building, as any glance from the drawings to the ceiling grid would affirm. The building seems unchanged, a tribute to the conservation job by the noted historic preservation architects Beyer Blinder Belle. They took into account the “patina” of wear on the rough concrete walls, bluestone floors, bronze fixtures, wood handrails and other features since its opening in 1966.

Marcel Breuer said he wanted to stick “close to Earth materials” as he created the third permanent home for the Whitney. He applied his hands to the cast concrete walls on a lower level, adding to the sense of craft that his Bauhaus training instilled. The building’s dark granite façade has long been a flash point among architects; some defended its Brutalist honesty while others saw it as a fortress of elitism—entered by a bridge over what seems a moat—defying the march of retail display windows along the Upper East Side. Nonetheless, the building has an undeniable sculptural presence. Nothing could send a more different message from the glass cube of the Apple store just a few blocks away downtown.

.

The Met Breuer. Photograph by Ed Lederman.

.

Vijay Iyer, a MacArthur fellow, Harvard professor and composer, is in charge of a “durational performance” of music that relates to the architecture as well as the art. The stops and starts of Iyer’sjazz-inflected music made mimetic sense for a museum through which the visitor moves between selective pauses.

The scheduled performances of several musicians and dancers extend from March 18 through March 31, 2016. Iyer and Wadada Leo Smith were commissioned to create “A Cosmic Rhythm with Each Stroke,” inspired by the work of Mohamedi, in two ticketed performances on March 30 and 31, at 7 p.m. in the Fifth Floor Gallery.

____________________________________

BASIC FACTS: The Met Breuer is located at 975 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10075. www.metmuseum.org.

Regular Hours (as of March 21):

Tuesday and Wednesday, 10 am–5:30 pm

Thursday and Friday, 10 am–9 pm

Saturday and Sunday, 10 am–5:30 pm

Closed Monday

_____________________________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.