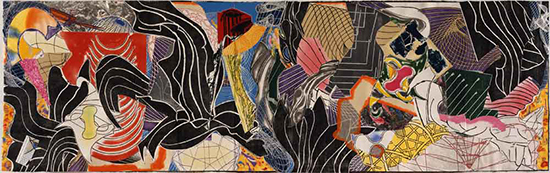

Dilating minds as well as pupils with nonstop optical and intellectual brilliance, the boisterous Frank Stella retrospective at the Whitney offers nearly 100 works: paintings, reliefs, sculpture, a monster print titled The Fountain on Ken Tyler’s custom paper, maquettes and drawings.

.

"The Fountain" by Frank Stella, 1992. Woodcut, etching, aquatint, relief, drypoint, collage, and airbrush. 91 x 275 3/4 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art; gift of Marabeth Cohen-Tyler and Kenneth Tyler 2015.97a-c. © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Steven Sloman.

.

The exhibition overwhelms the largest of the new building’s galleries as well as the curators and two architects: Renzo Piano, who designed the new building, and Annabel Selldorf, who was commissioned to create the installation. The experience is like trying to take a sip of water from an open fire hydrant.

Stella was involved in the hanging, powering through the day without lunch breaks, according to Whitney Director Adam Weinberg. The show abides roughly by chronology but verges on entropy under the pressure of so much visual information.

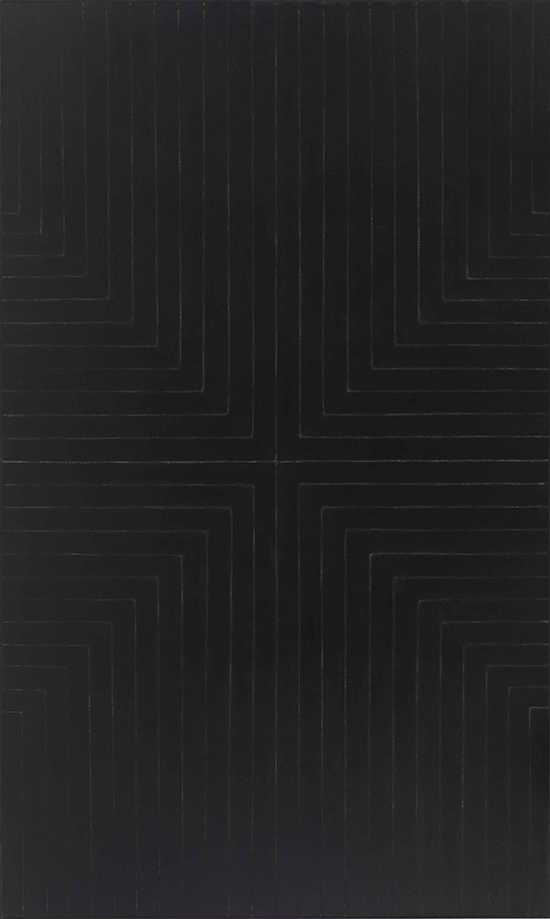

Like even the most monumental works that use theme and variations (think Bach, Goldberg), the show begins with an elementary melody. In 1959, Stella intoned labyrinths of vertiginous depth in the magisterial “Black Paintings,” the basso continuo of the exhibition (especially Die Fahne Hoch! and The Marriage of Reason and Squalor).

.

"Die Fahne hoch!" by Frank Stella, 1959. Enamel on canvas. 121 5/8 x 72 13/16 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene M. Schwartz and purchase with funds from the John I. H. Baur Purchase Fund, the Charles and Anita Blatt Fund, Peter M. Brant, B. H. Friedman, the Gilman Foundation, Inc., Susan Morse Hilles, The Lauder Foundation, Frances and Sydney Lewis, the Albert A. List Fund, Philip Morris Incorporated, Sandra Payson, Mr. and Mrs. Albrecht Saalfield, Mrs. Percy Uris, Warner Communications Inc., and the National Endowment for the Arts 75.22. © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image © Whitney Museum, N.Y.

.

Far from a single-minded reduction to the monochrome as an isolated pictorial element (these paintings are too frequently associated with minimalism), the series raised complex issues of rhythm, composition, surface effects (matte vs. glossy) and, most importantly, structure.

Plumbing their depths, I thought of a lyrical passage from Pinball the recently published early novel by Haruki Murakami:

“Outside it had turned pitch black. Not a monochromatic but a layered black, as if various black paints had been slapped on like butter. I sat with my nose to the taxi window looking out. As time passed, the black came to appear somehow flat, as if someone had taken a razor to matter without substance, and the darkness was the severed end. The result was a most odd perspective, at once three-dimensional and two-dimensional. A giant night bird with outspread wings rose before me.”

The “most odd perspective” created by the design of the concentric orthogonals survived the addition of color coding as Stella pushed into the copper and aluminum series, cutting out the “superfluous” (his term) negative spaces and building elaborate shaped canvases in the 1960s with dazzlers such as Empress of India (1965).

.

"Empress of India" by Frank Stella, 1965. Metallic powder in polymer emulsion on canvas. 77 x 224 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York; gift of S. I. Newhouse, Jr. © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

.

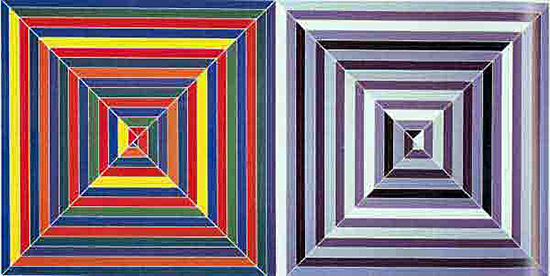

With the double maze of Jasper’s Dilemma (1962-63), Stella posed a question of such philosophical brilliance, an aesthetic dichotomy that is so utterly at the core of Modernist and even Postmodernist painting, that it stuns me as deeply as the many profound observations on composition and spatial relations he made during the course of his Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard in 1983 (collected in the indispensable volume, Working Space).

.

"Jasper’s Dilemma" by Frank Stella, 1962-63.

.

The enigmatic difference between the effect of the patterned works in black or gray and the spectrum of bright, artificial colors is a powerful demonstration of what it means for color to be called a “secondary” quality, after form. Two identical structures, one in a value progression from black to light gray and the other in brilliant tones, refer to Jasper Johns’s adherence to primaries and affinity for gray. A bright white edge separates the two.

I am not alone in thinking of Stella as a consummate colorist (and I feel as though I’m too old to like the neon in the later works) but in this pivotal piece he is a supreme dialectician on the subject. A crucial observation by the artist reflects this questioning tendency on the part of the scholar-painter: “There are two problems in painting. One is to find out what painting is and the other is to find out how to make a painting.”

Stella’s dilemma became the challenge of holding on to form’s integrity and also unfolding the proliferation of material and structural ideas that his painting had initiated. With the “Polish Village” series--including Bechhofen (1972) and its maze of painted forms--collage and large-scale constructions made literal the “bubble space” he identified in Caravaggio, Mondrian, Pollock and others during the Harvard lectures. The tempo zooms in the “Circuits,” based on race tracks (Stella, like Sal Scarpitta and Paul Newman, drove competitively).

As the Whitney’s Weinberg almost apologetically explained during the press opening (which Stella did not attend), the 90 or so works in the show represent a tiny fraction of the artist’s oeuvre—the “Moby Dick” series of painted metallic reliefs alone comprises 135 pieces, only six of which made the cut for the show. They include the vertical leviathan, The Whiteness of the Whale (1987) which is the epitome of Stella’s reading of Melville. Its gyrating white immensity powers down into the depths from under the curl of a green surface wave.

.

"The Whiteness of the Whale (IRS-1, 2X)" by Frank Stella, 1987. Paint on aluminum, 149 x 121 3/4 x 45 1/4 inches. Private collection. © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Steven Sloman.

.

The curators and Selldorf, the exhibition designer, faced an almost impossible task of selection and presentation. Either more space (the museum just expanded and yet the galleries were still extremely crowded) or tighter editing would have helped. These huge reliefs already burst into any gallery space, herding the viewers into the center, but the overarching design idea was to permit sneak previews of the work ahead, a curatorial and architectural principle explored more subtly by architect Yoshio Taniguchi in the re-design of MoMA.

One problem is that the din of vibrant color and explosive forms (even Stella admits, in a catalogue text, that the weightless feeling of the computer-aided design works from recent years displays “an excessive use of cantilever”) pushes the perceptual limits of even the most focused viewer.

The most splendid curatorial moment is revealed only by traveling to the west end of the building and confronting the monstrous, cinematic sculpture in shining aluminum and steel, Raft of the Medusa (Part I) (1990) against the huge windows admitting the pewter light of the Hudson River. Around the back of the towering piece, which alludes to the wild and iconic painting by Gericault at the Louvre, a steel beam bears a scrapyard inscription: “save Stella,” a warning to others that the piece was to be reserved for the maestro. It might have been a salient bit of advice for the curators, as well, to preserve him from his own and their excessive ambitions.

.

"Raft of the Medusa (Part I" by Frank Stella, 1990. Photo by Liu Ke Ming.

.

"Raft of Medusa" by Théodore Géricault, 1818-19.

.

Thank goodness some sages have stamina. Stella at 79 maintains the momentum of an express train, giving us the computer-aided reliefs, sculpture and the massive painting Das Erdbeben in Chili {N#3} (1999), which offers a fanfare to visitors as the elevator doors open on the fifth floor, where the exhibition is located.

The hefty catalogue offers substantive essays reviewing the series and an epic chronology tracking not just the shows but every review Stella has garnered in the past six decades. Also included is a chuckle-inducing interview conducted by Laura Owens, a painter of large-scale canvases who has been featured in the Whitney Biennial.

In the interview, Stella blithely explains why he chose the prolific composer Alessandro Scarlatti as the nominal basis for the latest series, “Scarlatti Sonata Kirkpatrick,” each of which is titled by a “K” number for Ralph Kirkpatrick, the scholar whose edition of the keyboard works is considered definitive. “That’s why I like the Scarlatti sonatas,” Stella said. “There are 500 of them, so I know that I’m not going to run out of them for a while.”

__________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Frank Stella: A Retrospective,” remains on view through February 7, 2016. The Whitney Museum of American Art is located at 99 Gansevoort Street, New York, NY 10014. 212-570-3600, www.whitney.org.

__________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.