“Reverse Engineering: How or Why?,” curated by Bill Powers and on view at the Fireplace Project, aims to mine a terrain that is usually associated with military and technological concerns.

In its presentation of the art of Josephine Meckseper, Alisa Baremboym and Aurel Schmidt, the show asks us to use the tools of code breaking to deconstruct what we are looking at: to ask how instead of why, to in effect take apart what the artist has assembled in order to understand the object’s underlying meaning.

It’s an interesting concept, and one that artists naturally engage in when viewing each other’s work. But for a general audience that usually brings a different set of expectations to an art show, the objects on display, even if they are complex, need to meet us halfway. Can such a show, I wondered, get beyond its provocative density and deliver something beyond itself?

Josephine Meckseper, a German artist based in New York, has said that she is “interested in making art as an experiment with an uncertain outcome.” In her collages and installations, Meckseper presents the realities of her immediate surroundings: signage, vintage photographs, underwear and everyday products, assimilating them into new forms.

In the case of her three pieces at the Fireplace Project, Meckseper has incorporated a chrome car rim, a pair of sunglasses and a feather duster, among other items, into her sculptures. Though her pieces are displayed on pedestals or hermetically sealed in acrylic—thus defining themselves as objects—almost all Meckseper’s works incorporate shiny or mirrored surfaces that mimic the retail environment. This use of reflecting facades suggests that the viewer is as much a part of Meckseper’s critique as the materialistic detritus she is commenting on.

For instance, in Cars, Cars, 2013, Meckseper has collaged pigment prints of car advertisements along with metal chains and glass crystal onto a brightly lit, mirrored panel. As the iconography implies, Meckseper holds the individual viewer just as responsible for the materialism on display as the larger, contemporary car-consuming culture. We are what we buy, she tells us. We’re part of the problem.

.

"Cars, Cars" by Josephine Meckseper, 2013. Metal fixtures, metal chains, glass crystal, pigment print on anodized aluminum on acrylic mirrored MDF slatwall with aluminum edging and fluorescent lights. 48 x 47 5/8 x 1 inches. Photograph by Lance Brewer.

.

Like film montage, Meckseper’s pieces are scenarios without literal narrative form. She is at her best when she is interacting with a specific site or an environment. In five pieces presently on view at The Parrish Art Museum, Meckseper has conflated the retail and advertising world of the Hamptons with references to art works from the permanent art collection. These pieces are high in concept but still precise enough to emotionally engage with the viewer.

Experimenting with combinations of hard and soft structures, Alisa Baremboym’s art explores the surreal integration of the human body with technology. Mixing unglazed, flesh-colored terracotta with leather straps and buckles, Baremboym creates objects that evoke both the sensual and the utilitarian, blurring the line between the organic and the mechanical. The resulting groupings often conjure images that are as sexy as they are disturbing.

In the Extender, 2013, Baremboym has laid a folded piece of ceramic that resembles a skin-flap atop a sharp-edged metal table. Wrapped around and holding together this flesh-like ceramic object is a USB extension cable. Baremboym has found a visceral and gripping way to show how the human body is almost undone without the technological world.

.

"The Extender" by Alisa Baremboym, 2013. Ceramic, usb booster extension cable, steel. 40 x 15 x 20 1/2 inches.

.

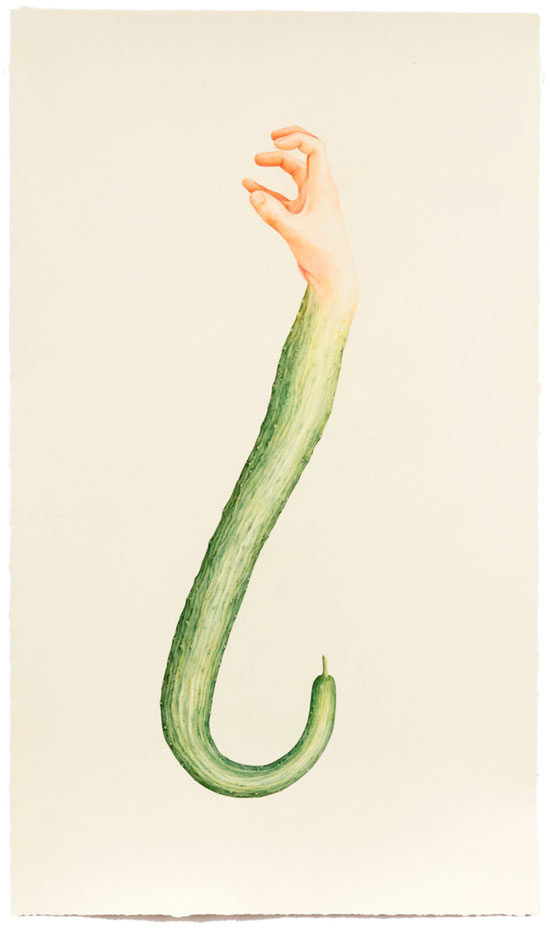

Finally, in small detailed pencil drawings, Aurel Schmidt, intermixes nipples and penises with fruit and vegetables to create fantastical imaginary creatures. Impeccably executed in soft pastel colors, some of Schmidt’s pieces, like Banana Dick, are a bit obvious. Who hasn’t seen the resemblance between that fruit and that body part before? Others, like Cucumber Claw and Ginger Toes, are by turns witty, inventive and menacing. It’s in these images, in which Schmidt pushes the kooky and bizarre edges of her fantasies into unfamiliar territory, that her work really shines.

.

"Untitled (Cucumber Claw)" by Aurel Schmidt, 2013. Colored pencil on paper. 34 1/2 x 20 inches.

.

To me, it seems that any artist who makes use of the detritus of the culture on which he or she is commenting runs the risk not only of having the work become that which it seeks to parody but also in danger of being overwhelmed by its subject matter so that it stops engaging with the viewer. Maybe I’m old-fashioned, but I get tired of confronting myself in someone else’s convoluted iconography. Worse, sometimes I can’t even find a way to connect to such works.

Because I want to engage with art, I’m willing to go much more than halfway. But I also want the artist to reach out through their work and pull me into an experience I wouldn’t have otherwise. I was able to break the code and reverse “Reverse Engineering”. Along the way, I discovered that most of the work in this show demonstrates, at least for me, that beyond the how, it’s the why that really matters.

BASIC FACTS: "Reverse Engineering" remains on view through Aug. 19, 2013. The Fireplace Project is located at 851 Springs Fireplace Road, Springs, NY 11937. www.thefireplaceproject.com

RELATED: "Josephine Meckseper's Parrish Platform Installation Opens at The Parrish Art Museum" by Pat Rogers.

________________________________________

© 2013 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.