After months of nothing but wild-eyed prognostications of the demise of globalism and rise of populism, the Frieze New York preview this week was a relief. Both international, with representatives from Mumbai, Seoul, Cape Town and Buenos Aires, and filled with the kind of work that claims its status as art instead of pop or counterculture, this year’s fair on Randall’s Island counters the dumber currents of current discourse.

The invigorating ferry ride to Randall’s Island turned into time travel as well as art tourism, thanks to installations dedicated to the art the ’80s. Skarstedt’s booth featured Mike Kelley and Cindy Sherman, while P·P·O·W parked a pigeon coop in the form of a car made by Anton van Dalen, which I vaguely recall from an Exit Art show in 1988. P·P·O·W also had historically significant works by Martin Wong and David Wojnarowicz, two of the more vocal artist-activists on the Lower East Side during that period.

During the trip from the 35th Street ferry landing, alert visitors can also enjoy an amazing Mark di Suvero sculpture rising alongside his famous crane at his studio on the riverbank just north of the tip of Roosevelt Island. In addition to a full program of lectures and panel discussions, Frieze is offering the “bespoke” experience of a personal art advisor to lead less experienced collectors to selected works for possible acquisition.

For this reviewer, there were artists who stood out at the fair, based on aesthetic rather than monetary value.

These are by no means the only artists who caught my attention, and in addition to this list I would add Carol Bove at David Zwirner’s gallery, Lorna Simpson at Hauser and Wirth, and the delicate graphite drawings and collages of Milano Chow at Chapter NY in the Frame section. Also, near the end of the seemingly endless tent, the Frith Street booth has a moving installation of the fragments of Jimi Hendrix’s staircase from the Mayfair townhouse in London where he lived, right next to the house of the composer Georg Handel. The title of the piece, by Cornelia Parker, is a wry summation of how one feels at that stage of traversing the length of a tent that has more than 200 gallery spaces under it: There must be some kind of way out of here.

.

"There must be some kind of way out of here" by Cornelia Parker. Mixed media installation of architectural fragments. Courtesy of Frith Street Gallery.

.

Lee Bontecou at Lévy Gorvy

I have been a Bontecou fan since writing about her magisterial wall sculpture in the Koch Theater lobby at Lincoln Center more than two decades ago, and the intimate scale of this untitled work from 1960 is a phenomenal entry point for understanding this reclusive and serious artist.

Always with Bontecou the dramatic high point is the black, black, black recess of a central aperture. Like the velvety holes of an Anish Kapoor sculpture, the optical properties of the black opening can make the mind reel. In this case, there are two irregularly shaped openings rather than the usual circular one, more like the organic holes in a tree inside which the owl waits for twilight. These are surrounded by very delicate cloth patchworks stitched with little copper wires and threads on a framework that resembles a vintage aircraft.

The concentric rhythms and suggestions of the nimble hands of the artist can be mesmerizing. Tucked in the corner like a whisper is the artist’s signature in what seems to be pencil. It may be delivered sotto voce, but the message of this masterpiece is profound. It was without any competition the absolute high point of the fair for me, and it did not escape my attention that a sculpture by another woman, Louise Bourgeois had similarly commanded my respect the night before at TEFAF’s opening (reviewed here).

.

"Untitled" by Lee Bontecou, 1960. Canvas, welded steel, and wire, 27 1/4 x 29 1/2 x 7 inches. Courtesy of Lévy Gorvy.

.

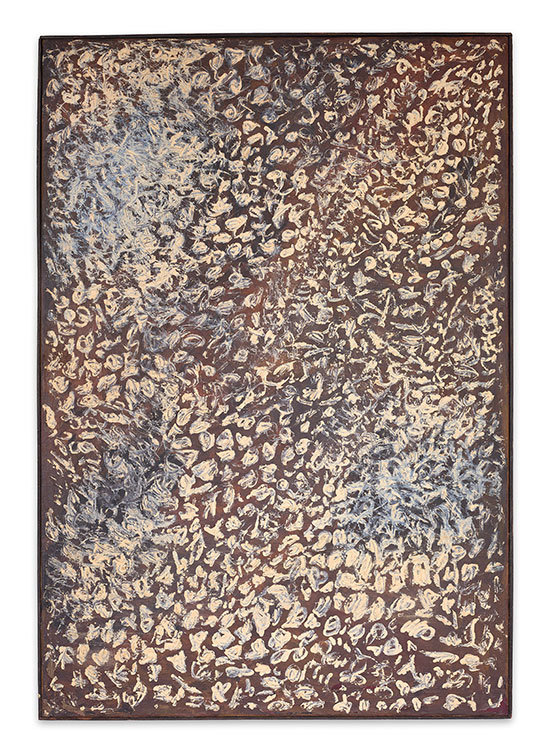

Masatoshi Masanobu at Axel Vervoordt

I confess that I found the vast Gutai Art Association retrospective at the Guggenheim four years ago to be too much of a good thing, but the elegantly mounted presentation at Axel Vervoordt of an important group of paintings by the member of the group who was present from beginning to the end is a valuable lesson in Modernism.

Masanobu was a star of the Gutai Art Association from its inception in 1954 to its end in 1972. They convened in Ashiya, near Osaka, and eventually comprised 59 artists. “Gutai” translates as “concreteness” and it is exactly that engagement with paint and canvas as materials that lends such drama to the Masanobu works on view.

Comparisons to Cy Twombly and Henri Michaux may be inevitable given the calligraphic characteristics of the paintings, which float fleeting strokes on richly layered monochromes. I was pulled by one white work that the gallery expert called uncharacteristic of Masanobu’s palette; he is known for his yellows, developed in landscapes. Still, the slicing and peeling of paint layers with a knife, right down to the brownish canvas, left such a battleground of scars that the “color as substance” (to use the artist’s words from the press release) was brought to the surface.

.

"Work" by Masatoshi Masanobu, 1961. Oil paint on canvas, 116.8 x W 80.3 cm. Courtesy of Axel Vervoordt.

.

Robert Rauschenberg at Thaddeus Ropac

Wall power in a fair is essential, and a pair of fascinating works by Robert Rauschenberg that uses the application of tarnish to brass and copper became beacons not just for fans of the masterful artist but for anyone attracted to the inventive use of materials.

Made in 1990, Rauschenberg used acetic acid and ammonium salts, brushed or silkscreened onto the brass or copper (in other cases, bronze) to gain an amazing range of effects. He prepared the light color areas by using solvents that would resist the tarnish. The effect is a version of the wonderful transfer imagery that made the paintings such panoplies of iconography, but with the harmony of the warm metallic tone to add the unity that the more colorful works sometimes lacked.

.

"Pinion (Borealis)" by Robert Rauschenberg, 1990. Tarnishes on copper, 36.75 x 60.75 inches. Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London • Paris • Salzburg. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York. Photo: Jessica Earnshaw.

.

Robert Motherwell at Bernard Jacobson

When the fair veered into retrospective territory, as in Jacobson’s heavy-duty hanging of a group of paintings and collages by Robert Motherwell, it slowed the pace of the relentlessly hungry visitors and demanded a different sort of attention. Among the large and important works by Motherwell on view—including a particularly interesting variant on the Elegy for the Spanish Republic—one collage was completely absorbing. Under glass, because it is so fragile, it took a snippet of Stravinsky’s score for the Rite of Spring and built a whole ballet of gesture and texture around it. Motherwell and music would be a terrific show (his Mozart collages are among my favorites), and this would be at the center of the program.

.

"Sacre du Printemps" by Robert Motherwell, 1975. Acrylic and pasted papers on canvas mounted on Masonite. 48 x 36 inches. Courtesy of Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

.

Etienne-Martin at Bernard Bouche

A fresh discovery for me at Frieze was the Giacometti-like plasters and wood sculpture of a little-known French artist named Etienne-Martin (1913-1995). A dreamer and a charmer, he conjured from humble materials (plaster, wire, fabric, a screen of old wood) compositions of surprising stature that the Parisian gallery presented along one understated row without fanfare.

It turns out that Etienne-Martin is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art and the Centre George Pompidou in Paris, but this was the first I had heard of him. The taste of the little figurative group, “personnages,” in plaster and wire, as well as the poetic evocation of his childhood home on the Cote d’Azur with its childlike inscriptions about the “chambre des fleurs” and “chambre des livres,” left me wanting more.

.

"Deux personnages" by Etienne-Martin, circa 1946. Plaster Ht: 34 cm. Photo: A.Ricci, Paris. Courtesy of Galerie Bernard Bouche.

.

_____________________________________

BASIC FACTS: Frieze New York is open through May 7, 2017 at Randalls Island (ferry service from 35th Street and 90th Street).

Hours: Friday: 11 am to 6 pm, special late tickets 6 to 8 pm, Saturday: 11 to 7 pm, Sunday 11 to 6 pm.

Visit www.frieze.com for tickets and more information.

______________________________________

Copyright 2017 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.