As spring brings back the tulips along Park Avenue and blooming trees along the stately side streets of the Upper East Side, a gallery walk in this part of the city is currently a trip down memory lane, with major exhibitions of Miró and Calder at Acquavella and Pace, Robert Morris at Castelli, and Mercedes Matter at Mark Borghi as clear highlights. In one afternoon art lovers can traverse three very special eras in art history, from Paris in the ’40s through New York in the Ab Ex era and into the Minimalist period that followed.

Mercedes Matter at Mark Borghi

This edited version of a mini-retrospective that was previously on view at Guild Hall in East Hampton as well as a trio of college art museums is a vibrant reminder of the major role played by Mercedes Matter, who—along with her friends Elaine de Kooning and Lee Krasner—was one of the pioneer women in the Artists’ Club and the WPA movement.

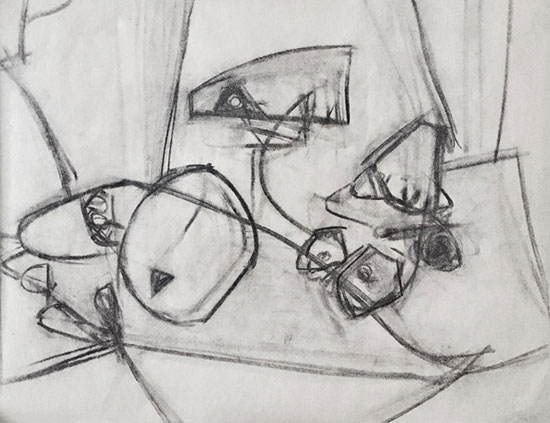

The exhibition at Mark Borghi in New York reaches back to 1929 with a rare self portrait and runs to paintings completed in the 1990s. Its greatest strength is the correlation of drawings and paintings, such as the tabletop still lifes, which offers a window into what has been referred to as the artist’s “observational based abstraction.”

.

"A Self Portrait" by Mercedes Matter, 1929. Oil on canvas, 16 x 12 inches. Courtesy of Mark Borghi Fine Art.

.

Delving further into the artist’s process, two of the still lifes made 60 years apart reveal the development of her palette and formal vocabulary. The Fauvist palette and bravura gestures are not surprising when one considers her family background and exceptional training.

.

"Untitled (Table Top Still Life)" by Mercedes Matter, 1936. Oil on canvas board, 20 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Mark Borghi Fine Art.

.

Born in 1913 in New York Matter grew up in Philadelphia, where she would become a noted teacher in her own right. Her father was the painter Arthur B. Carles, a protégé of Matisse, and her mother modeled for Edward Steichen. Her teachers included Alexander Archipenko, Hans Hoffmann (reviewed by Hamptons Art Hub here) and Fernand Léger, whom she assisted on a mural for the French Line during her stint with the WPA. She married the Swiss graphic designer Herbert Matter in 1939 and their home on Macdougal Alley was a gathering place for the titans of the era, including Pollock, Kline, and de Kooning.

In 1964, she founded the New York Studio School in a loft on Broadway, with Philip Guston, Bradley Walker Tomlin and other friends on faculty as well as Meyer Schapiro and the composer Morton Feldman.

Matter was a prolific writer and indefatigable worker in the studio up to the time of her death in 2001. This small retrospective at Mark Borghi not only shows the creative path from drawing to painting, it also offers insights into what made the artist’s contributions significant.

“Mercedes Matter—A Survey: Paintings & Drawings from 1929 to 1998,” April 6 to May 26, 2017 at Mark Borghi Fine Art, 52 East 76th Street, New York, NY 10021. www.Borghi.org.

.

"Untitled (Still Life) number1" by Mercedes Matter, 1936-38. Charcoal on paper, 18 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Mark Borghi Fine Art.

.

Robert Morris at Castelli Gallery

Five decades ago and more, a Saturday morning in the contemporary art world would inevitably start at Castelli Gallery in Soho, where the limousines of Si Newhouse and Asher Edelman would alternate outside as Castelli, with Mary Boone at the front desk, held court in the room at the back. And just about every year in that era, the powerful sculpture fashioned from felt by gallery star Robert Morris would cascade from the walls of the front rooms.

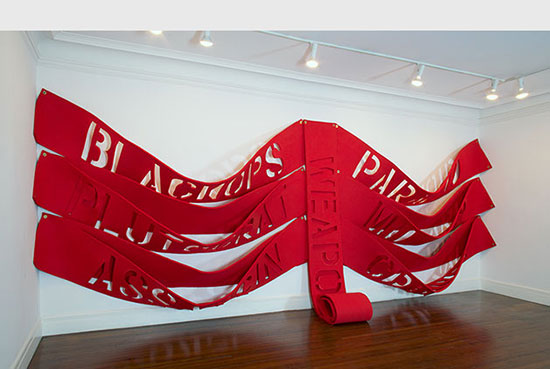

Today, retrospection comes naturally during a visit to the uptown Castelli space, even if the current Morris shows (one at 77th Street and one at the new, second-floor space overlooking Bryant Park on 40th Street) are all new. The sculptor is now riffing on his “classic” draped felt pieces, an idiom he has been exploring since the ’60s. The operatic curtain of red felt, one of three in the medium in the “Seeing As Is Not Saying That” exhibition at 77th Street, reveals a recent twist with the addition of text in a large stencil font cut into the ribbons.

.

"Gypsy Moth" by Robert Morris, 2016. Felt. Courtesy of Castelli Gallery.

.

The lettering is a reminder that Castelli also championed Jasper Johns, while the title of the show is lifted from a book by philosopher Donald Davidson. With “paranoid” and “weapon” in the lexical arsenal, these works are unfortunately not as subtle as the more Minimalist sculptures of the past.

The second Morris show, “Boustrophedons,” is on 40th Street in the new Castelli space, with the title taken from the Greek word for the winding text, sometimes used in illuminated manuscripts of the early Renaissance, that must be read alternately left to right and right to left. A dramatic quartet of giant installations, all in black carbon fiber, choreograph a Walpurgisnacht that twists and whirls the human figure into the sculptural counterpoint of this winding text.

Any fan of Rodin, especially his Burghers of Calais, will enjoy lingering among the six standing figures agonizing by the windows overlooking Bryant Park. I particularly admired a wall relief that reminded me of the Gates of Hell. The suspended flying hags at the other end of the room seem to have flown in from the pages of Goya’s album “Witches and Old Women.”

.

“Dark Passage" by Robert Morris, 2015. Cast carbon fiber. Courtesy of Castelli Gallery.

.

“Robert Morris: Seeing As Is Not Saying That,” February 24 to May 26, 2017 at Castelli Gallery, 18 East 77th Street, New York, NY 10075.

“Robert Morris: Boustrophedons,” March 10 to May 26, 2017 at Castelli Gallery, 24 West 40th Street, New York, NY 10018. www.Castelligallery.com

Joan Miró at Acquavella and Alexander Calder at Pace Gallery

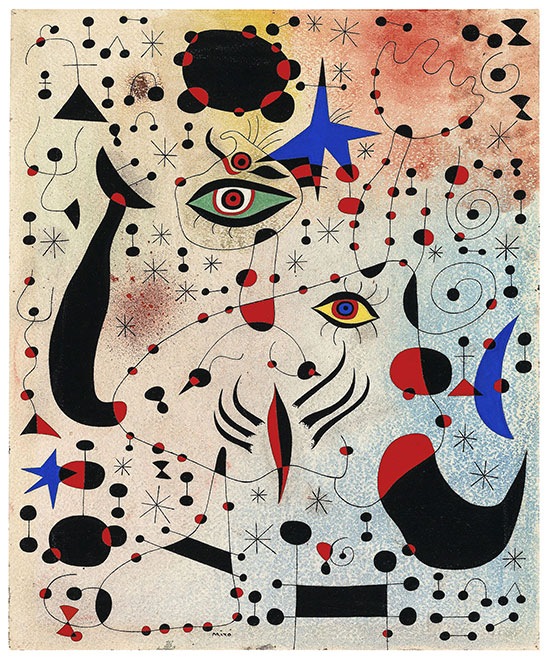

I have loved Miró ’s so-called “Constellation” paintings (small gouaches on paper) since seeing the complete series at the press preview for the great MoMA retrospective in 2011. The works were made in secret (he called them “furtive”) when the artist and his family were on the run from the Nazis in 1940.

Full disclosure, having been invited to talk about these paintings at the Acquavella Galleries on Saturday, April 22, 2017, I was able to preview the exhibition privately before it opened and was reminded once again of their power and elegance.

Dated on the back, the first 10 were made in Normandy, not far from where Braque was living then. When the Nazis reached Flanders, Miró headed to Spain. He stopped on Mallorca and in the cathedral of Palma found himself mesmerized by the reflections of the stained glass windows in the baptismal font. As the artist recalled, “I took a month at least to produce each watercolor, as I would take it up day after day to paint in other tiny spots, stars, washes, infinitesimal dots of color in order finally to achieve a full and complex equilibrium.”

.

“Chiffres et constellations amoureux d’une femme” (“Cyphers and Constellations in Love with a Woman”) by Joan Miró, June 12, 1941. Gouache and watercolor with traces of graphite on ivory wove paper, 18⅛ x 15 inches. Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

.

The effect is almost phosphorescent in these nocturnes at Acquavella, a swirl of forms linked by a dancing line in black that swings back and forth across the paper and makes diagonals, then loops in a suggestion of movement that captured the imagination of Jackson Pollock, who saw them in 1945 at the Pierre Matisse gallery in New York. These were early messengers from war-torn Europe and harbingers of the “all-over” compositions Pollock would make.

Knowing the story behind these fragile fantasies, many of which sport a delicate ladder leading to the stars, helps the viewer understand what a profound example they represent of art as escape from the evils of history.

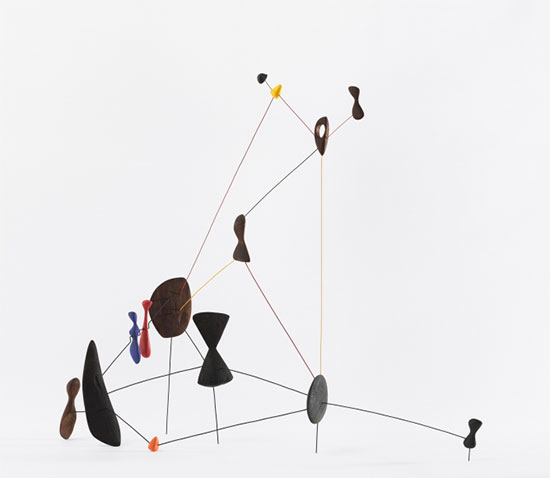

Acquavella and Pace Gallery teamed together for this show across the two galleries, connecting the Miró “Constellations” at Acquavella with Alexander Calder’s mobiles at Pace that use the same title, although neither of two series were actually named "Constellations" by the artists themselves. The historic basis for linking the two series is as solid as the works are evanescent, because Calder and Miró were great friends and the American sculptor was directly influenced by the Catalan’s style. Significantly, though, the two artists were not in communication during wartime when they were making their separate “Constellations” series, Calder having returned to the U.S. in 1938.

.

“Constellation” by Alexander Calder, 1943. Wood, wire and paint, 33 x 36 x 14 inches. Courtesy Calder Foundation, New York.

.

Their separation makes it all the more impressive to note the correspondence of the shapes, those black bow ties and the red and yellow “biomorphs,” from the plane of the Miró pictures to the wooden Calder forms (not the usual sheet metal of Calder’s pieces).

At Pace Gallery on 57th Street, the delicate Calder sculptures are generously spaced, including one relatively small one that is given a wall to itself. The unpainted wood in particular, and the modulated primary colors give them a warm, human tone, and it was illuminating to go from the sinuous black lines of the paintings at Acquavella to the straight black wires of the Calder sculptures at Pace, which resembled planetary models. Between the two, we get to overhear two astronomers, who had been expatriates in Paris together, in a dreamy conversation on the beauties beyond this planet.

"Calder / Miró : Constellations," at Pace and Acquavella Galleries.

“Miró: Constellations,” April 20 through May 26, 2017 at Acquavella Galleries, 18 East 79th Street, New York, NY 10075. www.acquavellagalleries.com

“Calder: Constellations,” April 20 through June 30, 2017 at Pace Gallery, 32 East 57th Street, New York, NY 10022. www.pacegallery.com

_____________________________________

Copyright 2017 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.