As a painter and printmaker, he distilled architecture into elegant compositions, coyly flirting with geometric abstraction while recording the modern world around him. This was the special gift of Emilio Sánchez (1921-1999), whose art reflected his long life in New York City and travels to the Caribbean and elsewhere in Latin America, including his native Cuba.

A vibrant sampling of his art is on view through May 21, 2017 in "Emilio Sánchez in South Florida Collections" at the Lowe Art Museum of University of Miami. The exhibit brings together 43 works, primarily paintings, as well as works on paper and various ephemera.

It's a gem of a show, glowing with Caribbean color and light, underscoring how much this artist is treasured in a region famed for innumerable connections to Cuban culture and history. Balconies and balustrades, as well as architectural elements of doors and windows, align to create a magical universe evoking the Cuban countryside, with its mix of rustic, Victorian, and colonial architecture. Other images offer carefully observed reminders of the artist's life in New York and travels to Latin America.

.

"Auto Glass, Bronx Storefront" by Emilio Sánchez, 1985-1989. Watercolor on paper, 22 1/2 × 30 inches, The Shelley and Donald Rubin Private Collection, New York. Courtesy Lowe Art Museum.

.

Emilio Sánchez was born into a landowning family of Camaguey, Cuba, a rural area known for its sugar cane, which was the source of his family's wealth. He was educated in the United States; included among the boarding schools he attended was Miami's Ransom Everglades. Later he studied at the Art Students League and Columbia University. During the years 1946 to 1959, he traveled and lived in New York, Havana, and the Caribbean, though after 1960 he did not return to Cuba. In his generation of Cuban-born artists, he's one of a few to live and work chiefly in New York.

"Architecture was almost his self-portrait," co-curator Victor Deupi told me during an interview at the Lowe on March 30, 2017. "Architecture occupied him for a significant amount of his work, not to say he didn't do portraits, still lifes, landscapes. Architecture is a vehicle for him to observe the world around him. It allowed him to look both into and out of. The building is really his own body, in a way."

.

"Yellow House" by Emilio Sánchez, 1965. Oil on canvas, 37 1/4 × 55 × 2 1/2 inches. de la Cruz Collection, Miami, FL. Courtesy Lowe Art Museum.

.

Few works depict people, and some architectural visions can at first project a haughty silence, almost but not quite akin to fastidiously designed jewelry in a window at Tiffany's. But close inspection reveals that these paintings and works on paper offer a sophisticated remix of traditions in art and architecture.

Each suggests a subtle chapter in a life wedded to a unique fusion of art and architecture within the far-ranging culture of the Americas.

With what might be considered a true exile sensibility, Sánchez has forged a bridge between two realms that may at first seem dissimilar. It's possible to see his art fusing together his realistic take on Caribbean domestic architecture with the formal, vibrant rhythms of geometric abstraction animating work by such Latin American artists as Carlos Cruz-Díez and Carmen Herrera. Herrera is another Cuban-born painter who has lived in exile in New York City for years; she received a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art considered long overdue in 2016, reviewed here.

A few years earlier, both Sánchez and Herrera were included in the traveling exhibit organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, "Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art," which made a stop at Miami's Frost Art Museum in 2014, reviewed here. In retrospect, with its focus on this impressive cultural legacy and given the current bitterly divisive issue of immigration, "Our America" seems more timely than ever.

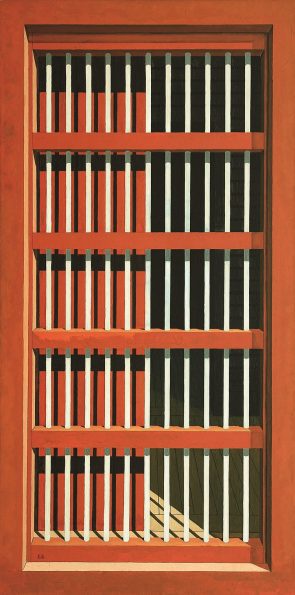

Geometric abstraction is a language Sánchez carefully embraced while never abandoning his intimate connection to architecture and realism. The bold, linear composition in El Ventenal/The Large Window by Sánchez shares an affinity with the optically vibrant, serial stripes in paintings of Carlos Cruz-Díez. Ostensibly, El Ventenal captures the severe contrasts between light and shadow as the intense light of high noon penetrates a window overlaid with a grille that lets tropical breezes flow through the building's living spaces.

The grille, which also protects those spaces from intruders, permits a glimpse inside into the dusky, obscuring shadows. Sánchez manages to portray the dark mystery of interior space beyond the window while simultaneously confounding the eye with a formal composition of flat, bold shapes repeated in vibrating, percussive bursts of black, white, and red.

Certainly it could be argued that the overlapping rectangles of blues and yellows in his painting Untitled (Ventanita entreabierta), very loosely depicting a window slightly ajar, recall the formal tensions implicit in Herrera's dramatic compositions of interlocking shapes.

.

"El Ventanal/The Large Window" by Emilio Sánchez, 1971-1973. Oil on canvas, 72 × 36 inches. Edmundo Perez-de Cobos Collection. Courtesy Lowe Art Museum.

.

There's still another cultural bridge that paintings by Sánchez construct: links from Latin America to North America. Occasionally threaded through his art at the Lowe are the sharp-edged rhythms of city life found in Edward Hopper's iconic 1930 Early Sunday Morning, with its row of apartment windows reduced to a series of shadowy rectangles spliced with a few boxy passages of dull yellow. The deep silence in this city scene by Hopper sometimes occurs in Sánchez paintings, particularly in Portales/Portals of 1997, with its angled procession of darkened doorways.

In fact, in his essay, "Emilio Sánchez, A New Yorker from Camaguey: A Latin American Perspective," scholar Rafael Diaz Casas observes that Sánchez was quite clear about his admiration for Hopper during conversations with Cuban art historian and critic José Gomez Sicre, who also lived in New York. This essay appears in the superbly illustrated 2011 monograph Hard Light: The Work of Emilio Sánchez, edited by Ann Koll.

Echoes of Edward Ruscha's iconic Pop art painting Standard Station of 1966, with its passages of bright, flat color and sharply angled perspective, further distinguish Auto Glass, Bronx Storefront by Sanchez, painted about two decades later. Sánchez appears to be playing around with his signature hybrid and "exile" aesthetic, perhaps adapting a Pop perspective to his 1980s portraits of Latino neighborhoods in New York.

His down-to-earth, street scene painting of the Bronx storefront seems eons away from the fanciful grandeur of Untitled (White House with Striped Roof), yet both illustrate his talent for teasing the boundaries separating geometric abstraction from compelling portraits of the built environment.

In vivid contrast to the precise architectural perspective detailed in Untitled (White House with Striped Roof), the surrounding grass, trees, and sky in this painting are resolutely flat, deliberately undercutting the painting's graceful realism. The rectangle of green on the door of the house, seemingly offering a view to the grass and trees beyond, evokes a minute nod to geometric paintings by Josef Albers.

.

"Untitled (White House with Striped Roof)" by Emilio Sánchez, 1999. Oil on canvas, 50 × 69 inches. Gift of Emilio Sanchez Foundation, Collection of the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum, Florida International University, Miami, FL. Image Courtesy of Lowe Art Museum.

.

For all his ties to Latin American art and his Cuban homeland, Sánchez never lost touch with lessons he learned as a "New Yorker from Camaguey." In New York, he studied with Reginald Marsh at the Art Students League in the 1940s, and became attuned to Marsh's gritty brand of social realism, honed during the Depression.

"Wherever he would go he would produce images of people and locals, the campesinos," said Deupi. "He was always more interested in the real, authentic character of a place than the kind of monumental image that society wanted to convey. That makes him a real, modern observer of the world around him. He was a flâneur."

___________________________

BASIC FACTS: "Emilio Sánchez in South Florida Collections" is on view February 9 to May 21, 2017 at Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, 1301 Stanford Drive, Coral Gables 33124-6310. www.lowemuseum.org.

____________________________

Copyright 2017 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.