Under the title, “Me, My, Mine: Commanding Subjectivity in Painting,“ the DC Moore Gallery in Chelsea is offering through July 29, 2016, a group show of seven painters that endeavors to do more than just exhibit the work of a group of artists for consideration.

Curator Carrie Moyer’s intention is for viewers to take notice of a specific aspect of the artists’ work, an aspect she succinctly outlined in a press release about the show:

“Motivated by the enduring interest in figuration ‘Me, My, Mine’ zeros in on the potential of commanding subjectivity in representational painting. Through their work, these seven painters generously extend an invitation to experience the prickly anxieties, obsessive self-scrutiny and extravagant fantasies that exist in the privacy of their own brains.”

It’s the subjects depicted in the paintings and the ways those subjects are rendered that viewers are especially asked to consider, subjects and attitudes toward them that prove to be quirky and amusingly odd. That this reviewer found most of it to be little more than that—amusing—may put me at odds with Moyer’s optimism regarding the implications of the show’s thematic line.

.

"Me, My, Mine: Commanding Subjectivity in Painting" at DC Moore Gallery.

.

Moyer’s organizing principle seems to be that artists willing to rely on highly personal non-sequitur can provide a way forward in the current and very welcome revival of representational painting. Though much of the work might be characterized as harmlessly strange, my difficulty with it was due to the general indifference each artist seemed to express toward the meaning of his or her imagery. Each canvas bears some compelling visual punch and a few traces of humor, but as reflections of human experience they struck me as consistently glib.

The largest canvas in the show, Peter Williams’s Shipwrecked (Gilligan’s Island), has diamond-patterned curtains opening onto a beach scene with several figures, some with culturally indelicate African-American features, and many seemingly representing the same, possibly autobiographical face. These loaded cultural tropes, though, are diffused by an anodyne silliness.

.

"Shipwrecked (Gilligan’s Island)" by Peter Williams, 2014. Oil on canvas, 60 x 132 inches.

.

Other smaller figures sprout mouse or rabbit ears, many with Pinocchio noses. The entire ensemble seems to be performing a sort of opera/circus. The random, playful tone is carried formally into overlapping and contradictory planes that make up the painting’s irrational space. One figure holds an ensign with the word “babel” on it. The ensign begs the question: whose babel—the classic sitcom’s creators, or the painter whose homage to the show is on view in this exhibition.

Sharon Madanes shares a similar flat and cartoonish look, particularly in regard to the largest of her works on view, an overhead perspective on a coroner’s lab, Cut Three Ways. The piece is organized around the image of a flayed cadaver rendered in abstracted detail, with the liberties taken in her renderings revealing a conspicuously disinterested attitude toward a fairly grim subject. The flatness of color and the minimally articulated gore emphasize the formal qualities of the painting surface rather than the mimetic aspects of the horrors on display. This bizarrely celebratory splaying of a human dissection appears to suggest that for Madanes a painting’s subject, no matter what it represents, is ultimately just a formal plaything.

.

"Cut Three Ways" by Sharon Madanes, 2015. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 80 x 112 inches.

.

Nadia Ayari’s evocatively titled abstract panels—“Tight,” “Safe Word” and “Multiple”—each feature a glowing violet orb set against a dark background. Random lines and other shapes float before its individual reiterations in a manner similar to the graphics of circa 1980s screensavers. A heavy texture overlaid with varnishing helps maintain each picture’s status as a painting, while adding what I found to be an unfortunately kitschy factor to the overall effect.

.

"Multiple" by Nadia Ayari, 2016. Oil on linen, 38 1/4 x 35 inches.

.

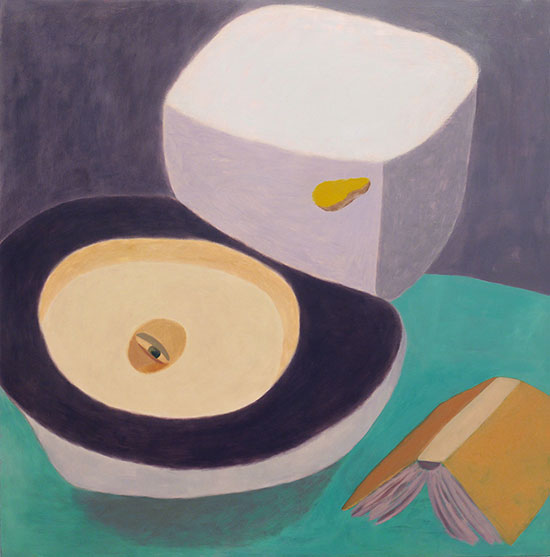

Ginny Casey holds to a calm and charming Milton Avery look. Her three-dimensional objects, vases, furniture and sculptural fragments, are built of flat planes of nuanced color. She then undermines their aesthetic solemnity by adding whimsical personae—an eye peeking out of a toilet in “Bathroom Reader,” or a pair of eyes looking out from under a jug in “Peeping Jug.” Both Ayari and Casey demonstrate a gentler form of extreme subjectivity. Of the seven participating artists, their work offers the least visual hyperbole.

.

"Bathroom Reader" by Ginny Casey, 2013-15. Oil on panel, 24 x 24 inches.

.

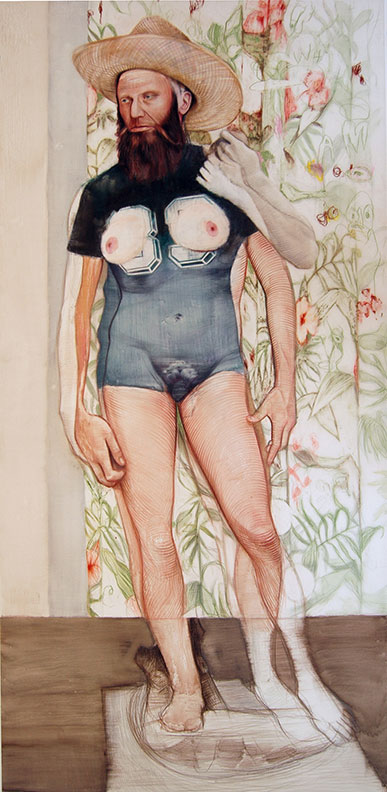

Geoffrey Chadsey’s work seems at first to break from the other artists’ generally impulsive attitude toward their subjects, but upon closer inspection reveals a similar cold alienation of feeling. His lopped (David) is a layering of a male figure’s portrait onto a sketch of Michelangelo’s David.

.

"lopped (david)" by Geoffrey Chadsey, 2016. Watercolor pencil on mylar, 85 x 42 inches.

.

The figure’s lower half, modelled in pinkish tones with an illustrator’s hatching technique, is interrupted at the groin by a more academically modelled rendering of the marble David’s abs and genitalia, appearing as if printed in monochrome blue on a tee shirt. The shirt bears athletic jersey numbers that in turn sprout two female breasts. Though constructed of identifiable and consciously juxtaposed parts, and hinting at the weightier issue of sexual identity, the total package fails to rise above its clever execution.

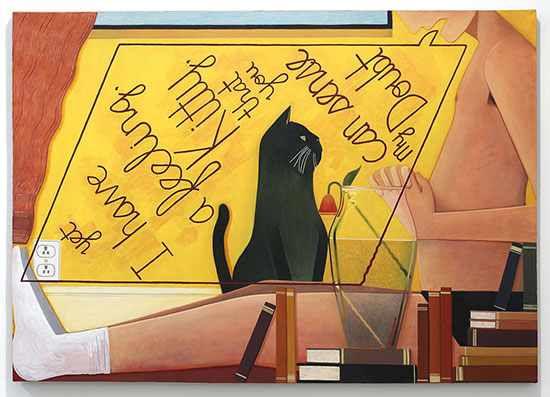

In Michael Stamm’s Winter, a window sitting atop the picture plane could have provided a vision of a dark December sky were it not for a cascade of wavy hair blocking the majority of the composition from upper right to lower left. As in Chadsey’s androgynous sentinels, this juxtaposition promises poetry, and in its own way delivers on that promise. The same cannot be said of a second painting, Yet I Have A Feeling (Kitty), which depicts a seated figure writing a letter to a cat. The deadpan elevation here of an inane idea characterizes Stamm as very much a participant in what I found to be the group’s collective, indifferent perspective.

.

"Yet I Have a Feeling (Kitty)" by Michael Stamm, 2016. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 34 x 50 inches.

.

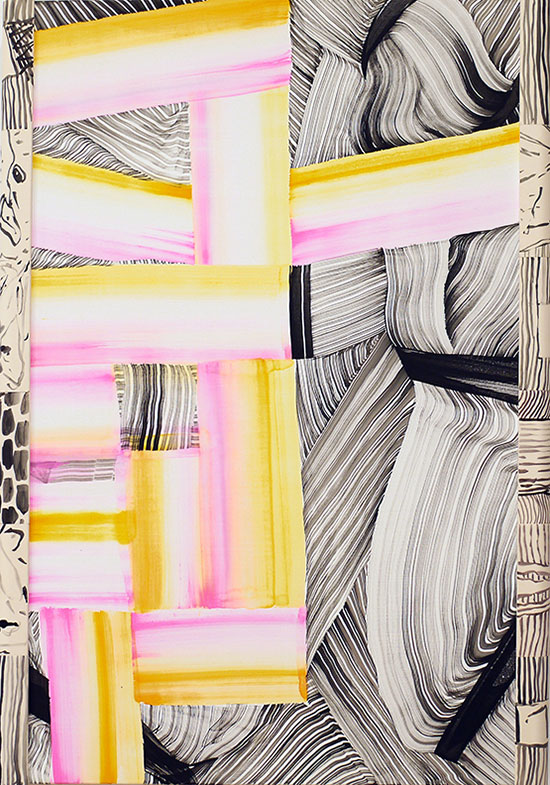

Julie Ryan, the one painter in the group devoted to an overt and purely surface oriented abstraction, fills her three canvases with strokes of black paint dragged over a white ground, striated by the brush, or whatever implement was used, to form parallel lines that twist and flow with the artist’s hand. These are offset by tube-like stripes made of colorful tints that keep to a hard-edged outline.

.

"Bread and Wine (St. John)" by Julie Ryan, 2016. Gouache and ink on canvas with ink and acrylic on ceramic, 36 x 25 x 2 inches.

.

I was tempted to consider the inclusion of Ryan’s work in the exhibition as a kind of touchstone, reminding the viewer of the bias toward both abstraction and spontaneity that together seem to define the attitude of the other six painters toward figuration. This suggestion—that an abstract mindset dominates the thinking of the whole group—perhaps points to the underpinnings of the curator’s radically freeform subjectivity.

“Me, My, Mine” implies that subject matter is nothing more than a personal gathering of inspired fragments to be treated as mostly formal elements—that a depicted image is selected spontaneously based on subjective criteria and its relevance to a viewer need not extend beyond the simple fact of its authorship. This looks and sounds to me like form equals content and content equals form. In what is probably the most quoted line of art criticism of the recent century, Clement Greenberg first suggested this formula in a 1939 essay entitled “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” which turned the tide of modernism with these words:

“Content is to be dissolved so completely into form that the work of art or literature cannot be reduced in whole or in part to anything not itself.”

These seven artists, along with their painter curator, seem to be suggesting an update of this old formalist principle. The innovation they bring is a willingness to replace the notion of removing subject matter altogether with incorporating content so divested of emotion that its imagery will not interfere with the aura of the painting’s overall appearance. There is no denying, as the exhibition demonstrates, that talented painters can apply this method to paintings that hold one’s interest. But for me the interest is of momentary duration at best, because what they offer are mannerist elaborations of what seem to be deliberately unprocessed thoughts.

In the conversation regarding today’s welcome and much needed opening of the whole question of subject matter, “Me, My, Mine” makes a genuine contribution. It is an important exhibition to see. The issue it addresses is crucial to our understanding of current trends in painting and where they may lead.

Beyond this, though, I see the show’s premise as more of a warning than a way forward. To reintroduce representational imagery into painting in a way that seems purposefully superficial and impulsive can serve to reduce images to a kind of impotence. And this sort of reduction, in turn, has the capacity to upend the whole enterprise of allowing painters the freedom, if not the mandate, to address subjects that have a deeper meaning for the rest of us.

__________________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Me, My, Mine: Commanding Subjectivity in Painting” is on view June 16 through July 29, 2016 at DC Moore Gallery, 535 West 22nd Street, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10011. dcmooregallery.com.

__________________________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.