With a major work on view at the Whitney Museum, Lee Krasner is far from obscure. Nonetheless, the current survey at the Robert Miller Gallery, by revealing a continuity in her process that is often missing in other shows, has a solid claim on the attention of those who might feel they know her historic place in the renowned circle of Abstract Expressionists.

The last major retrospective of Krasner’s work stopped in at the Brooklyn Museum 15 years ago. The current show’s credibility is built in part upon the two-decades-long friendship between Betsy Miller (co-founder and current president of the gallery) and the artist.

When Le Krasner (1908-1984) was uncomfortable being alone in Springs after the death of her husband, Jackson Pollock in 1956, it was Betsy Miller—whose husband Robert was a studio assistant to Krasner in the 1960s—who often kept her company. Miller acknowledges in her memoir that Krasner could be “irascible,” but also captures her generosity toward the Miller children, and her vulnerability. The intimate bond ensured not only a pipeline of major loans for the exhibition but an implicit grasp of Krasner’s intentions and patterns based on firsthand knowledge.

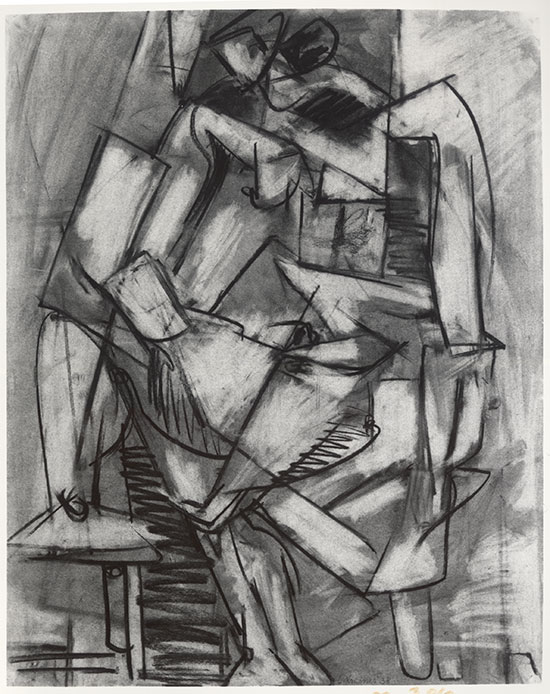

This kind of insight is particularly clear in a bold stroke of curatorial juxtaposition in a front room of the gallery. On the one hand, there are two of Krasner’s early charcoal drawings, life studies made under the watchful eye of Hans Hofmann at his Eighth Street atelier that combine Cubism and expressionism. Counterbalancing these are collages from the 1970s in which similar drawings from the period are cut into Matisse-like shards and enter dialogue with painted forms.

It all starts with the High Modernist Nude Study from Life (1938), a densely worked and accomplished study. For the aptly titled Past Conditional (1976), a large horizontal composition that layers bold, opaque painted forms over a procession of charcoal drawings, the pointed contrast with the previous work is a commentary on change over the course of a career. This becomes the keynote of the exhibition, progressing from a self-portrait made in 1931-33 to some of the latest paintings Krasner made before her death.

“All my work seems to swing back to something I was involved with earlier,” the artist once observed. Decades conflate in single works that combine fragments of the drawings from the 1930s, loose gestures toward the painterly whirlwind of the ’50s, and the tight edges of the ’70s.

.

"Nude Study from Life" by Lee Krasner, 1938. Charcoal on paper, 25 1/2 x 20 inches. © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Robert Miller Gallery.

.

"Past Conditional" by Lee Krasner, 1976. Collage on canvas, 27 x 49 inches. © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Robert Miller Gallery.

.

Lee Krasner's biographical background is widely known at this point. Born Leonore Krasner in Brooklyn on October 27, 1908, she received academic training at the Cooper Union, National Academy of Design, and Art Students League (the basis for her confident life drawing) before joining the Public Works of Art Project in 1934. Three years later she became a pupil of Hofmann, whose influence on her thinking and characteristic handling of paint is everywhere present in the show.

Krasner was fiercely intellectual, which lends a thoughtful context to the paintings. Ralph Waldo Emerson is one of the reference points in the show, reflecting her interest in philosophy. Her fascination with language comes through in a large, light-filled calligraphic work from 1965 titled Kufic, as well as in the tightly painted, untitled schematic grid of 1949 that stacks hieroglyphics in meticulous boxes.

.

"Untitled" by Lee Krasner, 1949. Oil on linen, 38 x 30 inches. © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Robert Miller Gallery.

.

For all the heady metaphysics, though, she was still part of an intensely physical movement in art. Everywhere there are traces of the deft hand for the figure that she developed early in her career. The rigid straight line of a thigh intersecting with arched arms resembles the drawing style of other students of Hofmann, such as Fritz Bultman, and sets up a vocabulary of mark making that is found even in the most abstract of later works in the show.

The steady vertical divisions of the canvas and the vortex of curved forms that converge from the corners are compositional elements that committed formalists will follow from wall to wall in the show. Hofmann’s floating rectangles of color are echoed in Equilibrium (1951), one of the few works in the show that does not swing those full-arm, stately and dignified curves.

Krasner’s The Seasons, with its green and rose palette, has been taking its star turn at the Whitney Museum, and other works from the ’60s and ’70s use those colors as well, making them one of the most familiar signs of her style. Seen in the gallery, though, paintings such as Palingenesis (1971) offer so much more in the way of tonal variety than they seem to sport when seen in reproduction.

.

"Palingenesis" by Lee Krasner, 1971. Oil on canvas, 82 x 134 inches. © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Robert Miller Gallery.

.

The range of pink, scarlet, maroon and other variants on the rose is astonishing, and the different applications of the green—from a thinned wash that soaked into the canvas at the upper left corner to a heavy skin near the center—lend textural and chromatic variety to the large work. The crescent forms are limned in a white edge that reminds me of the way photographers “solarize” their solid forms with a flick of the darkroom light switch.

No amount of abstraction can obscure the strong sense of personality in the gallery. Viewers with something on their conscience will be stopped in their tracks by the cocked left eyebrow of the little self-portrait across from the desk. It shoots a withering glance that I imagine was familiar to such targets of her ire as Harold Rosenberg (whose partisan 1952 essay on the action painters seemed to tacitly favor Willem de Kooning) as well as the obstreperous Pollock himself, referred to by the gallery staff, always with titters, as “Mr. Krasner.”

.

"Self Portrait" by Lee Krasner, 1931-33. Oil on linen, 18 x 16 inches. © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Robert Miller Gallery.

.

Like the early Elaine de Kooning self-portraits shown last summer at the Pollock-Krasner house in Springs (and reviewed here), the Krasner self-portrait presents a tough cookie dramatically coiffed and ready for a tiff.

As Simon Schama so splendidly demonstrated in his study of Rembrandt, the eye of the artist is a vital motif, a psychological and symbolic focal point that recurs subtly at the Robert Miller Gallery in Krasner’s haunting series of “Umber” paintings that are the climax of the show. Painted at night by a grieving insomniac using a restricted palette of white, black and a brown that is close enough to dried blood to cause discomfort, these works are the mighty culmination of the exhibition.

The vast centerpiece of the series on the last wall is the largest Krasner still in private hands. Under a skylight, other Umber paintings glower down from three sides of the gallery with a tremendous visual as well as emotional power. Distinctly rendered eyes peer out from the web of flung arcs. At the upper left corner of Vigil (1960), the eye is angular and narrowed, with hints of Picasso (although Krasner favored Matisse) surrounded by briskly blended passages that recall the tempestuous backgrounds of vintage Kandinsky.

.

"Vigil" by Lee Krasner, 1960. Oil on canvas, 88 3/4 x 70 inches. © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Robert Miller Gallery.

.

The historical and biographical arena in which the Umber paintings were made palpably yields a theme of combat, of an urgent effort at artistic and personal rebirth. Krasner died in 1984, shortly after her first major museum retrospective opened at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, and before it could arrive in New York.

Rather than an art historian, the gallery intrepidly tapped Patti Smith (who shows at Robert Miller) to write the catalogue essay, which recounts her own arrival in New York in 1967 at age 20 with Krasner on her mind. She emulated the artist’s “strength of purpose” and longed for an ideal partnership with another artist (Robert Mapplethorpe, also shown at Miller) that would somehow wed art and love.

Smith’s strident essay celebrates the strong-willed negotiation of the difficult balance between personal and artistic commitments: “Lee Krasner was steadfast in her engagement with these two seemingly conflicting vows … Her steely determination projects from an early self-portrait and the work thereafter provides us with the markers toward her eventual full-bloomed entry into a male dominated world, forever establishing herself on equal ground, where aspects of gender may enrich a work, but not determine its place within the circle of Art.”

_________________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Lee Krasner” is on view April 21 to June 4, 2016, at Robert Miller Gallery, 524 West 26th Street, New York, NY 10001. www.Robertmillergallery.com.

__________________________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.