BEACON, N.Y. & NEW YORK CITY - To start the new year in a truly contemplative mode, one need only take advantage of two closely related Dia Art Foundation exhibitions of the painter Robert Ryman’s work—one at Dia Chelsea and the other at Dia Beacon.

Ryman’s work is often spoken of in terms of a pronounced quietude, but a full appreciation of its extended roots—effectively accomplished in the two Dia shows—can enrich the experience. The different emphases in the two locations invite a comparison that sharpens the viewer’s focus on the visual complexity of Ryman’s work, while also demonstrating how his work relates to a deeper history of the contemplative in western visual art.

The Chelsea show concentrates on color, highlighting the artist’s early development of his exclusive and by now signature choice of white paint. The Beacon show concentrates on his attentiveness to the ambient light that has such a profound effect on a viewer’s experience of the work. The Chelsea show echoes formal concerns similar to those of early modernism, while the Beacon show seems to touch upon that period’s infatuation with spirituality, a phenomenon that was itself a revival of a much older aesthetic.

Umberto Eco, in his short volume Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages, addressing medieval notions of beauty, makes a compelling distinction between how in the middle ages, the essential properties of light—from the sun or a flame, for example--were understood differently than the light that emanated, as was then believed, from an object’s color. Eco believes this is why color was often intensified in both painting and poetry. As he wrote: “There were superlatives for every color—for example, praerubicunda for roses.”

Eco notes, too, that unmodulated color abounds in medieval painting as well. Intriguingly, he goes on to footnote his argument with the qualification that “In the writings of the mystics […] and those of the Neo-platonists in general, light was always a metaphor for spiritual realities.”

By the 15th century Western painting had supplanted the symbolism of color with modeling and illusion of all varieties and did not return to the symbolic mode until the 1880s, when flat, abstracted color returned, often conjoined to spirituality—notably in the art and writing of Kandinsky and Mondrian. But while the use of intense monochromatic color has continued into the new millennium, the spiritual aspect has clearly faded.

Recent artists addressing an aesthetic of light itself, notably Dan Flavin, James Turrell, Nancy Holt and Robert Irwin, did so in a clearly secular context. Today, a pervasive ironic bias keeps spiritual connotations in check, limiting attempts at expressing spirituality to modes of flirtation. But the mysticism of light cannot be totally separated from the experience of it, any more than the human response to color can be fully intellectualized.

The Ryman shows in Beacon and Chelsea separate these two through lines of his work and place him within a historical weave that includes more than a few threads leading back to the 12th century, when artists relied on a highly intuitive metaphysic.

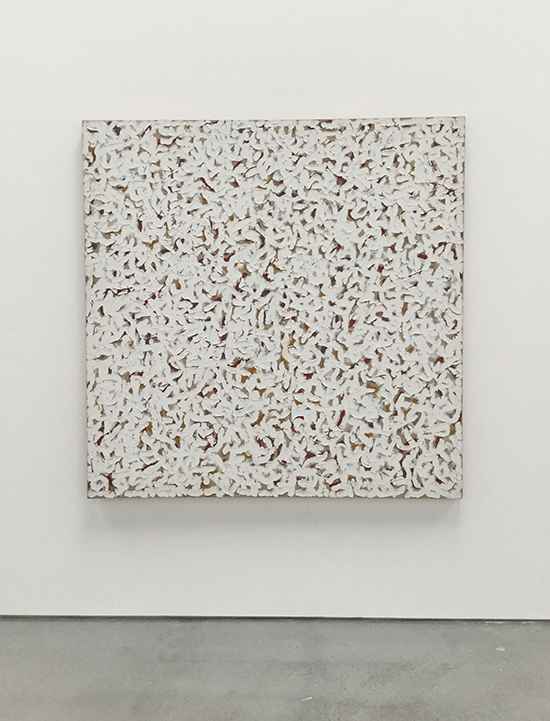

The Chelsea show is a sort of mini-retrospective that guides a visitor’s attention along Ryman’s early development. Half the entries are dated prior to 1970 and reveal immediate influences, like the tendency to spread a field of color shy of the frame’s edges, as in “Untitled, c.1960,” or the application of strokes of white pigment that partially cover an underpainting of primary colors, as in Untitled (Background Music), 1962.

.

"Untitled" by Robert Ryman, c. 1960. The Greenwich Collection Ltd. Photo by Peter Malone.

.

"Untitled (Background Music)" by Robert Ryman, c. 1962. Oil on Linen. Photo by Peter Malone.

.

The remaining work, which follows Ryman’s commitment to white, concentrates on the artist’s experimentation with painting supports. Unusual examples include oxidized copper plates dressed with white enameled corners, a horizontal white panel extending out from the wall like a low table (unfortunately warped the day I was there by damp weather), and most intriguing, a panel of brushed aluminum with sharp, near machined edges of black paint, perhaps in imitation of the edges and sides of so many panels of differing materials.

What’s special about this panel is that its color field is not really white in the conventional sense, but consists of the metallic surface itself, reflecting the white of the gallery space. Great care was obviously taken in choosing the level of polish that would reflect the ambient light to the degree required by the artist, which it might be assumed would have meant blurring the details of the room. But reflective detail is not entirely obliterated in the photo I took of the piece, as can be seen in the barely visible gray shade of my own diffused silhouette.

.

"Catalyst III" by Robert Ryman, 1985. Enamel on aluminum with steel bolts. Private Collection. Photo by Peter Malone.

.

White can take on whatever significance a viewer brings to a Ryman painting, including symbolic notions of emptiness, purity, infinity—quite a few of these can be found in chapter 42 of Melville’s whaling epic. But as the artist evolved, and particularly with the sponsorship of the Dia Foundation, lighting considerations became an increasingly important part of the installation process, and it is this aspect of Ryman’s work that is on full display at Dia Beacon.

Here the artist was given considerable control over the building’s skylights. Filters were added and work was displayed according to the character of the light that defined each gallery. As visitors to Dia Beacon can attest, the natural light that fills most of the galleries changes slowly as the day progresses and can change quite suddenly as clouds pass over.

Predictably, this fickle atmosphere affects the mutable color in Ryman’s work, creating an odd paradox: the “color” in a textual sense is always white, or at least in a stable relationship to the white walls, on which the works are pinned, screwed or hung. This is particularly noticeable in regard to the most radical painting at the Beacon exhibition, the large Varese Wall, 1975, which is propped up a few feet away from the larger gallery wall behind it.

.

Robert Ryman, installation view, Dia:Beacon, Riggio Galleries. © Robert Ryman Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Bill Jacobson

.

Transformed by fleeting effects from the skylights above, Varese Wall, 1975 acts as an amplifier of the relationship of light, color and space that is both inescapable and crucial to the work as a whole. Mechanically controlled light, easily available through LED technology, would have better maintained the appearance of the work in a conventionally curatorial sense. But the artist chose instead to allow nature to interfere with the work, even to the extent of momentarily robbing the painting of its unique and specific material characteristics.

.

Robert Ryman, installation view, Dia:Beacon, Riggio Galleries. © Robert Ryman Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Bill Jacobson

.

This choice indicates to me how Ryman’s seemingly radical body of work is very much part of a long tradition in western art, a tradition that oscillates between the spiritual and the secular, or between the votive and the experientially mystical. Its precursor would be the soft purple light of the nave in Chartres cathedral, produced by sunlight passing through glass panels of intense, pure color.

Today’s advanced understanding of the science behind light and color does little to change the actual effect of experiencing both in Ryman’s paintings. In the end, the artist’s work is all about accentuating and re-mystifying the elusive wiles of visual experience itself. White panels on white walls—even while begging questions about process, objects, light and color—subdue the art and leave viewers standing in the space, feeling the sky above.

_______________________________

BASIC FACTS: "Robert Ryman" remains on view through June 18, 2016 at Dia Chelsea, 545 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011. www.diaart.org, 212 989-5566.

"Robert Ryman" is on Long-term View at Dia Beacon, 3 Beekman Street, Beacon, NY 12508. www.diaart.org, 845 440-0100.

_______________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.