When Donald Baechler is accorded Old Master status, as he is in the meticulously presented exhibition, “Donald Baechler: Early Work 1980 to 1984,” at Cheim & Read in Chelsea, then I have to concede I am growing long in the tooth. It’s one thing to grant Ellsworth Kelly and Jasper Johns this status, but I remember vividly the large-scale paintings of Donald Baechler, enfant terrible, in what many writers called the “kids’ room” at the notorious Whitney Biennial of 1989 (Mike Kelley was another denizen of that particularly raucous sector of the show).

That was the headache of a Whitney Biennial that Arthur Danto, in a review in The Nation, called “a toyland for sophisticates.“ He connected the figures in Baechler’s paintings to “projected enlargements of drawings a child might have made.” By the time of the 1989 Whitney Biennial, Baechler, who was born in Hartford in 1956, was a certified star of the ’80s scene in New York (where he still lives and works) and had started to rack up the international reputation that is now manifest in his many solo shows in Italy, Spain, Austria and elsewhere.

His bold and instantly recognizable large paintings, many print series and monumental sculpture have made him a major presence in museums from the Fisher Landau Center in Queens (which has a stunning group of Baechler’s work), MoMA, the Whitney and the Guggenheim in New York to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Pompidou and Musee National d’Art Moderne in Paris and the Rupertinum in Salzburg. His sculpture lined Park Avenue for months, and a huge, monumental work landed, amid a rash of controversy, at Gabreski Airport in Westhampton.

A full art history lesson on Baechler can be found by coupling the Cheim and Reid exhibition, revealing the rise of his visual vocabulary, with a show of new paintings at Sargent’s Daughters on East Broadway.

In the Cheim & Reid show, the European connection is significant. I did not realize that after Cooper Union, Baechler headed to Germany and became part of the Neue Wilde movement, which included the efforts of Jiri Georg Dokoupil and Martin Kippenberger. The drawings in this show reflect the influence of Kippenberger throughout.

An art history game could be fashioned from this charming and beautifully curated exhibition, one that involves tracking traces of the later Baechler in these early but far from tentative essays. The greater epistemological challenge is the impossible question of judgment without the help of hindsight: If these works were presented at the front desk of a Chelsea gallery today, would the artist get a shot, or be shown the door? Both questions issue invitations to close looking, and many of the large-scale works on heavy paper, attacked with a range of media—from graphite and oil-based enamel to spray enamel, acrylic, tempera and rough paper collage—reward study.

Baechler is at home in the play of black against white, and there are some glorious whites in these galleries: chalky, creamy, hoarfrost tinted. The pallor of these works is endemic—they line the room in ghostly portraits wafted in from a volume of Emily Dickinson. The essential formula for a Baechler floats an open, boldly traced black figure over a ground of whites and color, the more distressed and worked the background the better. Simplicity is the hallmark of the black figure, like a stencil or stamps of silhouettes.

One untitled work from 1982, for instance, is a life study of a nude male, perched on a stool and thrusting his left foot dynamically out of the picture plane toward the viewer as he pulls on a boot. Behind him a trellis of grey stripes with three vertical bands of a flesh-tone pink strikes me as jail-like, as though the figure wanted to come out from behind bars (the same background is found in Resort Group (Food) Second Version of that year. The three-dimensional effects are optical and literal, the layers and the clever use of the bars to divide space.

.

"Untitled" by Donald Baechler, 1982. Oil based enamel on paper, 46 x 35 inches. Courtesy Cheim & Read.

.

"Resort Group (Food) Second Version" by Donald Baechler, 1982. Oil based enamel on paper, 46 x 35 inches. Courtesy Cheim & Read.

.

My favorite Baechler effect is the palimpsest, the simultaneous layering of the principal image (often crude) over a vigorously painted, sprayed and collaged surface replete with drips and fast trills of brushwork and suffused with light greys, blues and greens. Two large works dedicated to the iconic Egyptian singer and songwriter Oum Kalsoum (“the Star of the East,” as she was known) have a Giacometti-esque atmosphere, billowing greys surrounding the figure with a nimbus of delicate smoke.

I especially recommend a group of figure studies, the best of which is Reclining Nude (After Shelby Creagh) from 1982, which trades classic linear life drawing marks for a heavier, angled black line that in many ways can be extended from these early works into the idiom of the silhouette for which he is best known.

.

"Reclining Nude (After Shelby Creagh)" by Donald Baechler, 1982. Acrylic, graphite and muslin collage on paper, 40 x 32 inches. Courtesy Cheim & Read.

.

Moving it forward through time, Sargent’s Daughters on East Broadway offers “Donald Baechler: New Paintings”.

The exhibition of new work at Sargent’s Daughters is all in the same large format (40 by 40 inches) Baechler has used since the 1980s, hung in a witty way that pairs just two works per wall.

The viewer who is familiar with the artist’s work, and the novice, will naturally gravitate to a signature image, the rose limned in black suspended over a spectral field of green, red, blue and yellow, a summery statement that will always be in season. Titled The Caustic Peninsula (2015), it has everything one looks for in a painting by Baechler, including the bubble-like drifting circular forms that look as though they were pressed into the acrylic (these are collaged in fabric and mounted on jute).

.

"The Caustic Peninsula" by Donald Baechler, 2015. Acrylic and fabric collage on jute, 40 x 40 inches. Courtesy Sargent’s Daughters.

.

I was glad that I had had the circular imprint of a coffee cup pointed out to me at the Cheim & Read show, because it allowed me to realize that a little moment of carelessness with the ceramics in the studio could have led to this circular form design element in the later work.

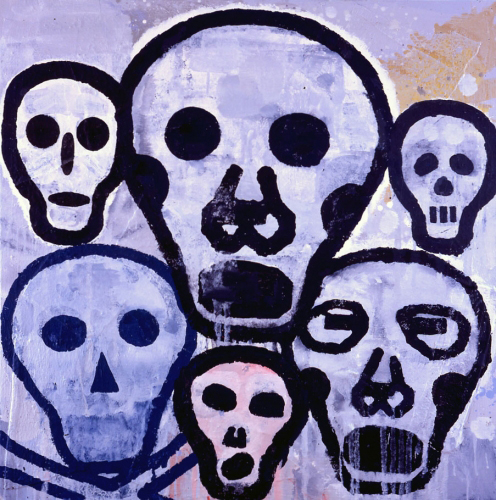

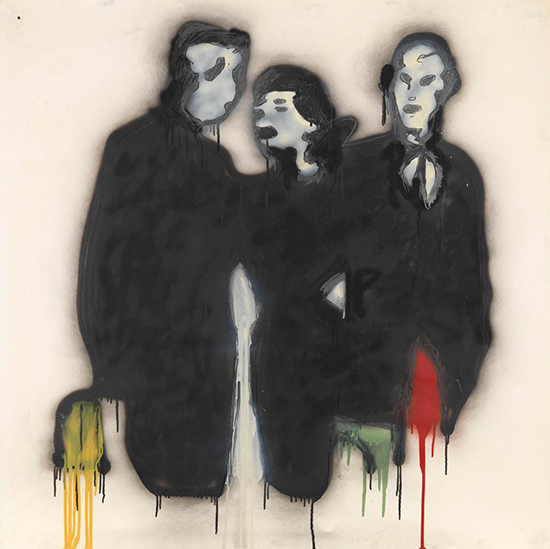

The mood darkens in Crow Painting (2005), a dense array of six skulls over a sickly purple (the pleasure of the comic background has been traded). This, too, has its antecedent in the early drawings: a triple portrait, Three Figures (Wall Street Week), from 1980 uses dripping spray blasts of yellow, moss green and blood red with a Goya-esque black. The woman turns toward her companion on the right, separated by a phallic white form, ignoring the longing gaze of the tie-wearing gentleman to her left, forgotten.

.

"Crow Painting" by Donald Baechler, 2005. Acrylic and fabric collage on canvas, 40 x 40 inches. Courtesy Sargent’s Daughters.

.

"3 Figures (Wall Street Week)" by Donald Baechler, 1980. Graphite, spray enamel and oil-based enamel on paper, 42 x 42 inches. Courtesy Cheim & Read.

.

In the new work, the ’80s keep calling. The dramatic interplay evokes the stage work of David Mamet and a blurred, spectral version of Robert Longo. Elegiac and disturbing, it shows why Baechler is so well-loved in Austria, the breeding ground of Expressionism.

There is nothing like turning the clock back with strong exhibitions like these, but it can exact a price, especially when the edge wears down. Nostalgia felled Gatsby, whose desperate effort to recover a golden moment in his past is the paradigm for retrospection: “‘Can’t repeat the past?’ he cried incredulously. ‘Why of course you can!’”

_________________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Donald Baechler: New Paintings,” November 18 to December 20, 2015 at Sargent's Daughters, 179 East Broadway, New York, NY 10002. 917-463-3901; www.sargentsdaughters.com

“Donald Baechler: Early Work 1980 to 1984,” November 24 to December 30, 2015 at Cheim & Read Gallery, 547 West 25th Street, New York, NY 10001. 212-242-7727; www.cheimread.com

__________________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.

perfect ending for poets

Great article on an artist I’ve watched for years.