The super bowl of art fairs has landed once again in the balmy climes of South Florida, sprawling across what seems like several counties with massive tents, conventions halls, random hotels and fixed museums stuffed with contemporary art shipped here from all over the planet.

The locals see it as an economic phenomena and every bus boy, cab driver, and shoeshine kid leads off the conversation with “Are you here for Basel?” before going all street art critic, with detailed directions to their favorite sculptural installation that appeared the past week.

It is a citywide phenomenon and the locals know, for reasons somewhat unclear, the literati have made their city the chosen one, the global center of intellectual culture for a week or two among the palm trees.

The center ring is Art Basel Miami Beach, held at the cavernous Miami Beach Convention Center on a barrier island a mile off Miami. Now in its 14th year, the fair encompasses 267 galleries from 32 countries, all of whom fought like cats in a bath to spread their wares onto a tiny bit of real estate.

Two rings of security personnel smiled at my press badge as I entered the center from the east side and unfortunately made a left turn into the Nova section, bearing the subtitle: “platform for younger galleries.” I liken this to having meandered off the interstate in the dark at the wrong exit and wandering into a neighborhood of cul de sacs—while driving on one headlight, a flat tire, out of gas, and with three kids crying for their supper. Life in the horror lane.

This area was cluttered with work by what I affectionately call the “young and the useless,” a generic MFA show where derivative work is obfuscated with theory and dreck.

In the music world they love to showcase prodigies who learned their instrument at a young age: the 6-year-old Midori Gotō performing Paganini or 7-year-old Jeronimo Maya plucking a soleares from currents in the air. But sometime around puberty these enfants terribles tend to disappear for a decade or so, or perhaps forever, as the little-kid novelty wears off and they must learn to weave adult moods and phrasing drawing on a depth they may not have.

The Nova show was filled with people who may be able to create an artwork in 10 years or so, but who do not seem up to the task of doing so now. This is not tiny Midori stroking a Caprice, this is Britney, age 8, banging Moonlight Sonata on the Sears spinet at Thanksgiving.

Hamptons artist Steve Miller met me as I was leaving Nova. When I relayed my misgivings, he offered that “Nova has an aesthetic also.” But I could tell from his unglazed eyes that he hadn’t actually been there yet. Soon after, lawyer to the art stars Michael McCullough phoned me to say the other side of the room was great, so we headed in his direction across the vast floor, hoping to find the promised land.

The fair seemed somewhat bigger this year and, outside of Nova, certainly offered work of greater depth than seen over the past decade or so. I noticed at the Frieze fair on Randall’s Island in New York last season that art had suddenly become unshiny, a roundabout way of explaining that the art world seemed to be coming out of two decades of facile Pop art and now the herd was ambling to a new watering hole.

I saw exactly one chromed sculpture at Art Basel, and it looked about as contemporary as a yard sale album of Donna Summers singing “McArthur Park.” Glad to put that chapter away.

A surprise at Art Basel this year was a voice from the past at the Leo Castelli gallery. The influence of Castelli on art in New York City, and Pop art specifically, cannot be overstated: there would have been no art world in ’60s without him. His widow continues to run his gallery on east 77th Street with an ongoing program of mature excellence.

The gallery’s entire space at Art Basel was given over to a rewarding installation of Keith Sonnier (b. 1941, Louisiana). Sonnier is associated with many movements of the 20th century, including scatter art, process art, light art and other forms of post minimalism. This installation did not disappoint and the cognoscenti were congregating around this modest booth like Catholics at the Vatican.

.

Keith Sonnier at Leo Castelli Gallery booth.

.

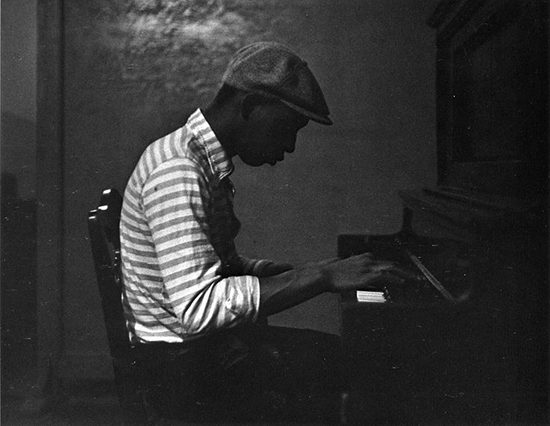

The Castelli booth was part of a group of 14 galleries set aside by Art Basel for historical projects, defined as art made before 2000. In addition to Sonnier’s work, another great from this standout feature of Basel were the vintage gelatin silver prints by Roy DeCarava (1919-2009) at the Jenkins Johnson Gallery.

DeCarava has become a collectors’ favorite recently for his inimitable film noir images of the jazz era of Harlem, especially those from his volume “The Sweet Flypaper of Life.” The radiant tones and timing of the images make him a life force for any photographer to reckon with.

.

"Man in striped shirt at piano" by Roy DeCarava, 1954.

.

"Duke Ellington in 1967' by Roy DeCarava.

.

Another feature of this year’s main fair, repeated for the 11th year by my count, is a group of curated galleries with the title “Kabinett.” These 27 curated exhibits are scattered among the rest of the offerings but share a theme of a single artist each. The late performance artist Chris Burden is featured at Galerie Krinzinger with a hand painted binder of his self-inflicted painful pieces created from 1971 to 1973.

The standout individual piece for the fair has to be a piece by Damien Hirst, whose preserved dove suspended in a vitrine at White Cube gallery was the Art Basel favorite. This is a bit of a surprise, as Hirst blew out his name selling silly dot painting to any rube who could write a check. But here he is in his early mode, working directly with animals preserved in tanks.

His most famous was a shark suspended in formaldehyde with the catchy title The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. Seems the title lasted longer than the piece, as it was redone with a less threatening shark and became about as imposing as any other dead fish in a barrel.

Hirst redeems himself with The Incomplete Truth, which is an amazing image and instantly recognizable as his work. The dove is neither morbid nor ripped to bits, as are most of his animal pieces. Instead it is a soaring image on the level of Picasso’s Dove. It rightfully sold for $3.5M the morning of the first day.

.

"Dove of Peace" by Pablo Picasso, circa 1949.

.

"The Incomplete Truth" by Damien Hirst, 2006.

.

_______________________________

BASIC FACTS: Art Basel Miami Beach remains on view through December 6, 2015 at Miami Beach Convention Center, 1901 Convention Center Drive, Miami Beach, FL. www.artbasel.com.

_______________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.