North Miami's Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) is redefining itself amid its own "reverse diaspora." Now on view at the museum, "Ars Memoria" is a thoughtful selection of more than 40 artworks from its permanent collection. There was a moment, though, when it seemed a possibility that these artworks might never again be shown at MOCA, as they could have been permanently displaced from their museum "homeland."

MOCA's permanent collection and reputation have been irrevocably altered. In January, this 709-piece collection was legally divided between MOCA, established in 1996, and Institute of Contemporary Art Miami (ICA), established in Miami's Design District in 2014, following an acrimonious and highly publicized legal dispute between the two institutions. As a result of court-ordered mediation, ICA claims 210 works. MOCA keeps the remaining 499, although those numbers may vary as MOCA's de-accession process is ongoing, according to MOCA's Assistant Director of Education and International Programs Adrienne von Lates, PhD.

Embedded in this controversy are pentimenti-like layers of irony. MOCA's origins can be traced to a smaller community-focused art venue in North Miami. Given that it's located in a city with a large Haitian American population, notions regarding diaspora are vital to the museum under the current leadership of Director Babacar M'Bow, who co-curated this exhibit with von Lates. Said von Lates of M'bow, "He really wants us to focus on artists of the Caribbean."

A highlight of "Ars Memoria" is Cargo Cult, created for MOCA in 2005 by Cuban-born José Bédia, who has exhibited internationally while living in Miami for years. But even before he left Cuba, his international stature was already taking shape: Bédia's art was included in two landmark exhibits, the 1989 "Magiciennes de la Terre" at George Pompidou Center in Paris and the 1992 "Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century" at New York's MoMA.

Speaking about Bédia's Cargo Cult, von Lates said, "We felt it was a very, very important piece of diaspora art," given the artist's longtime interest in cultural anthropology.

An expansive installation occupying two adjacent walls, the work features one of Bédia's signature, oddly proportioned, silhouetted black figures with elongated arms lunging toward cargo ships rendered as simplistic white outlines on a gray background. Many of the vessels bear small and lusciously painted blue and white flags, denoting rain storms. But overall, the dispassionate, flat outlines contrast mightily with the black figure's dramatic form. At the center of this piece, on the floor, is a simple wooden boat loaded with grains of rice.

.

"Ars Memoria; Selections from the Permanent Collection." MOCA Gallery Installation: José Bedia, "Cargo Cult," 2005, Mixed Media Dimensions variable, Purchased with funds provided by Rosa and Carlos de la Cruz and Diane and Robert Moss. Photo by Francesco Casale, Courtesy of MOCA North Miami.

.

Cargo Cult evokes disturbing side effects of clashes that can occur when cultures from various regions scatter across the globe. The title refers to a late 19th Century religious movement arising primarily in the South Pacific. Indigenous peoples began to worship Europeans for bringing so many goods or "cargo" to their countries, spurring locals to believe that they could also attract wealth by constructing their own symbolic boats, wharves, ships or planes. Bédia's art aims to underscore manipulative deceptions inherent in many trade relationships between First and Third World countries.

The artist has also often explored destructive remnants of colonialism. In 2008, Cargo Cult was exhibited in a Wynwood warehouse operating for a few years as a MOCA satellite, established to show exhibits during a never-realized expansion of the North Miami site.

Memory & Moving Forward

"We call this show 'Ars Memoria' because that's Latin for art of memory," von Lates said during an interview at MOCA on July 28, 2015. "We believe that all museums are repositories of the world's memory, but MOCA has this unique history now with all the controversy and all the drama. We need to acknowledge our history and also envision how we are going to step forward."

To give context to "Ars Memoria," it’s important to understand some back story. This ugly "tale of two museums" ignited endless rumors and speculation in Miami and beyond.

After several months of speculation about museums merging or not merging, the dispute erupted in March 2014 when North Miami Mayor Lucie Tondreau announced at a city council meeting that MOCA board members had told her they were planning to move the museum's collection and operations to the Bass Museum of Art in Miami Beach.

Officials in North Miami, a working class city in northeastern Miami-Dade County that owns the building and contributes to the museum's budget, reacted with outraged surprise, resolving to block the move. A month later, the MOCA board sued the city for not maintaining the building and other offenses.

At that time, MOCA had already appointed Alex Gartenfeld as interim director of MOCA. The city, meanwhile, appointed Babacar M'Bow as MOCA director. But the MOCA board rejected the city's decision. So, for an embarrassing time, both men claimed the same position.

One harbinger of impending disaster: In 2012, North Miami voters nixed MOCA's request for the city to issue bonds for $15 million for an expansion project that would include more exhibition space for the permanent collection. This was not, in fact, the first time MOCA's plans to expand fell flat.

In 2007, MOCA Executive Director and Chief Curator Bonnie Clearwater announced plans for a $18 million expansion to triple exhibition space and add more amenities, including an outdoor sculpture roof. "We already have a reputation that far exceeds our building," Clearwater told The Miami Herald then. "Now we'll have a building that will make it possible for us to do more." Yet there was to be no expansion as announced in 2007, as funds from the board, other donors, and the city never materialized.

Possibly the 2012 loss at the polls was the last straw for Clearwater and MOCA's board. In July 2013, Clearwater, who had led MOCA since it opened in the Charles Gwathmey-designed building, resigned to direct Nova Southeastern University Museum of Art|Fort Lauderdale. Curiously, in a November 2013 Art in America magazine interview with Clearwater, she told the magazine that since MOCA's expansion was under review with the board and the city, it was an "opportune time" for her to change jobs.

In May 2014, sanity finally intervened: MOCA and the City of North Miami embarked on court-ordered mediation to resolve their differences and find alternatives to the Bass merger. The former MOCA board was reconstituted as the ICA board. ICA opened with exhibits for Art Basel Miami Beach 2014 and is now temporarily located in a facility in Miami's Design District, with plans for a 37,500-square-foot building opening in December 2016.

This unfolding controversy has been painful for many in the local art community, who had watched MOCA, exhibiting both Miami artists and artists with international reputations, grow in stature several years before the resounding success of Art Basel Miami Beach, Art Basel's first art fair outside of Switzerland.

Small Groupings, Big Themes

As for the current exhibit, coherently bringing together more than 40 artworks in different mediums by more than 40 artists is no mean feat. For the most part, the show succeeds. It's carefully paced with small groupings evoking big themes, from romantic desire and bodily violence to cultural clashes and anguished loss.

.

"Ars Memoria; Selections from the Permanent Collection." Moca Gallery installation, left: "Let's Spend the Night Together (Hampton 81)" by William Cordova, 2001. Acrylic, ink , gouache and graphite on paper, 50 x 107 inches. Purchased with funds provided by Paula and Joel Friedland in honor of Irma Braman. Photo by Francesco Casale, Courtesy of MOCA North Miami.

.

Near the entrance is a photograph by Anna Gaskell depicting two girls asleep on the grass, dressed to recall storybook illustrations of “Alice in Wonderland.” But their outfits appear too young for their age. The photographs cleverly suggest the "calm before the storm" turmoil of girls on the verge of adolescence or adulthood. And are they twins or lovers? Nearby is Inka Essenhigh's Romantic Painting, an exuberant composition flirting with nearly baroque abstraction even while portraying a passionate embrace.

.

"Ars Memoria; Selections from the Permanent Collection." MOCA gallery installation, left: Anna Gaskell, "Untitled # 8 (wonder)," 1996, C-Print, 30 x 40 inches, Museum purchase with funds from the Janet and Robert Liebowitz Acquisitions Fund Right: Inka Essenhigh, "Romantic Painting," 2002,Oil on panel, 52 x 64 inches, Museum purchase with funds provided by Victoria Hughes and John H. Smith, Carolee and Nathan Reiber, Warren Miro, Jeanne and Michael Klein, and the Pop Soup fundraiser. Photo by Francesco Casale, Courtesy of MOCA North Miami.

.

There's also the exquisitely fragile-looking, baroque excess of Untitled 757, Petah Coyne's Murano-reminiscent chandelier hanging from the ceiling. Its scores of hardened, melted white wax droplets could stand in for blown glass ornamentation or the dustily preserved wedding gown of a jilted bride, in the manner of another famous fictional character from Dickens, Miss Havisham.

.

"Ars Memoria; Selections from the Permanent Collection." MOCA gallery installation, foreground : Petah Coyne "Untitled 757,"1993-2004 Wax, 48 x 38 x 39 inches. Gift of Neuberger Berman. Background left: Anna Gaskell, "Untitled # 8 (wonder)," 1996, C-Print, 30 x 40 in. Museum purchase with funds from the Janet and Robert Liebowitz Acquisitions Fund , Right: Inka Essenhigh, "Romantic Painting," 2002, Oil on panel, 52 x 64 in., Museum purchase with funds provided by Victoria Hughes and John H. Smith, Carolee and Nathan Reiber, Warren Miro, Jeanne and Michael Klein, and the Pop Soup fundraiser. Photo by Francesco Casale, Courtesy of MOCA North Miami.

.

Detail of "Untitled 757" by Petah Coyne, 1993-2004. Wax, 48 x 38 x 39 inches. Gift of Neuberger Berman.

Photo by Francesco Casale, Courtesy of MOCA North Miami.

.

Easily seen from these artworks is the large and commanding Entropy of Love by Mariko Mori. Slightly the worse for wear from time in storage, it's a riveting, early example of the artist’s signature way with digital photography, contrasting alien scenarios with colorful landscapes and elaborately costumed, sexualized self-portraits.

.

"Ars Memoria; Selections from the Permanent Collection." MOCA gallery installation showing Mariko Mori, "Entropy of Love," 1996 . Photograph on aluminum, plywood and formica, 120 x 240 x 2 inches, Gift of the Artist and Deitch Projects, New York. Photo by Francesco Casale, Courtesy of MOCA North Miami.

.

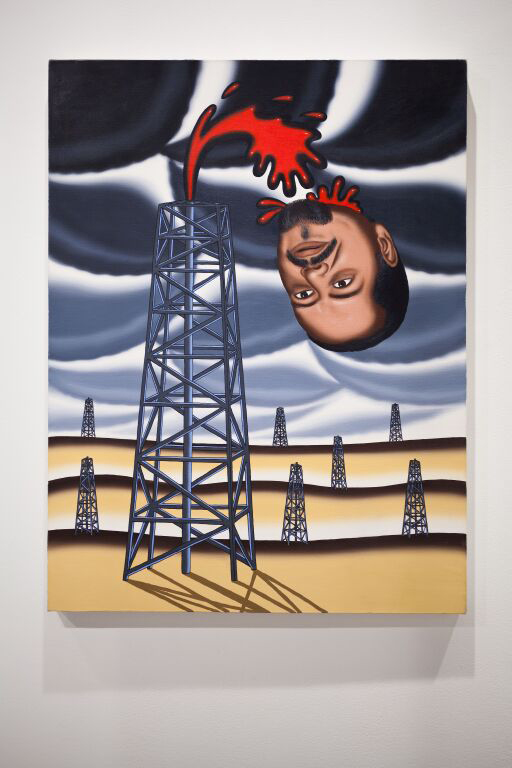

Another intriguing section, with various imagery of human heads, might bring to mind recent terrorists' acts of beheading, though these artworks pre-date those acts. All are visually compelling in their own right, but this grouping adds a new, discomforting layer to their significance. These include Roger Brown's painting Arab Oil Sheik, with a sheik's head floating bizarrely above oil derricks, and Ruben Torres Llorca's sardonic portraits of art critics and art dealers.

.

"Ars Memoria; Selections from the Permanent Collection." "Arab Oil Sheik" by Roger Brown, 1986. Oil on canvas, 48 x 36 inches. Gift of Estelle and Paul Berg. Photo by Francesco Casale, Courtesy of MOCA North Miami.

.

There's also Portrait by Leon Golub, in which a somber visage emerges from a reddish thicket of brushstrokes. Opposite is the nearly abstract sculpture Head by Magdalena Abkanowicz.

Though not simultaneously visible, other works address notions regarding diaspora and displacement, as well as clashing cultures. A Logo for America by Alfredo Jaar speaks to the common practice, by many in the U.S., of using "America" to refer to the United States, although the U.S. is part of the continental mass of North America, along with Mexico and Canada. Ali Prosch's acerbic black-and-white video Not My Mama, apparently set in a swampy South Florida locale, uproots conventional notions regarding "a woman's place."

Greeting visitors is one of MOCA's newest acquisitions, Mother Earth by Edouard Duval-Carrié, a Haitian-born artist living in Miami. Art by Duval-Carrié, who has exhibited internationally and had a recent solo show at Pérez Art Museum Miami, had never been part of MOCA's permanent collection until now.

Mother Earth, a rich blue and green portrait, depicts the Haitian Vodou goddess of love, Erzulie, a mythical figure linked to West African spiritual lore. The piece is ornamented with intricate designs called vévé, found in Haitian Vodou temples and offers a vivid example of the artist's abiding focus, the transforming migration of West African beliefs to the New World, especially the Caribbean.

That's yet another grand story of diaspora for the transformed MOCA to tell as it moves forward.

_________________________________

BASIC FACTS: "Ars Memoria" is on view through August 30, 2015 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Joan Lehman Building, 770 NE 125th St., North Miami FL 33161 www.mocanomi.org.

_________________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.