At 88, painter Athos Zacharias has the energy and enthusiasm for artistic exploration of a man one quarter his age.

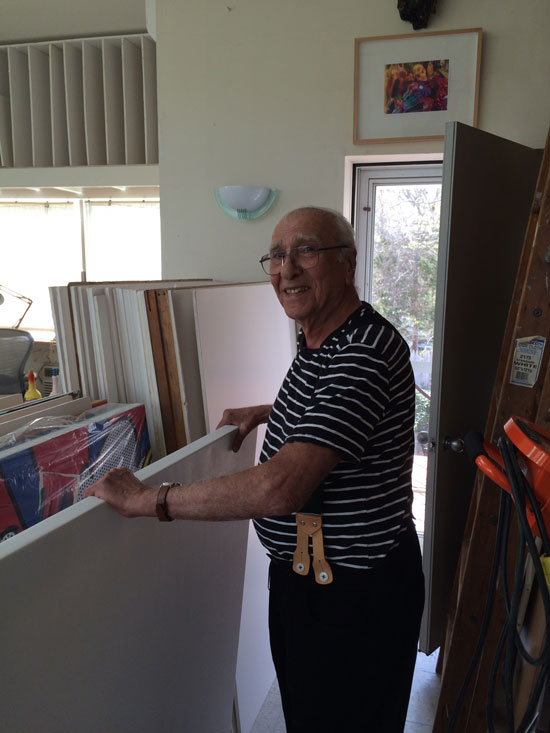

Clad in a striped t-shirt and suspenders, he showed a visitor around the expansive studio on the second floor of his home in Springs on Thursday, May 7, 2015, just two hours before the opening reception for “Athos Zacharias: Taking Chances,” a new show of never-before-seen works from the 1990s at Lawrence Fine Art in East Hampton.

.

Athos Zacharias in his studio. Photo by AB photo.

.

Zacharias, who goes by Zack with just about everyone, bounced as he talked, moving from one table covered with press clippings and exhibition announcements to a counter holding hundreds of brushes and tubes of pigment. He kept talking as he rambled from one corner of the studio to another, flipping through a stack of paintings leaning against a desk before pulling a chair up to his computer and then spinning in his seat to rifle through a set of giant drawers where other visual notes and paintings and appropriated images were stored.

Athos Zacharias “discovered” eastern Long Island in the 1950s through his associations with such New York and East Hampton painters as Willem de Kooning, Elaine de Kooning, Alfonso Ossorio and Lee Krasner. He noted in passing that he worked on the house and studio for 26 years before he considered it completed.

With the show of 35 smaller works on paper opening that evening at Lawrence Fine Art, and another show—this one of larger paintings on canvas—opening at Chase Edwards Contemporary Fine Art in Bridgehampton May 23, 2015, Zacharias was only too happy to talk about both shows, his ever-evolving process, and where he stands now in his artistic journey.

As he climbed the stairs to his studio, he said that one reason the works at Lawrence Fine Art have never been seen before is that “I never showed them, never even showed them to a dealer.” He added that he didn’t show anything or make any effort to show or sell his work for years because he wanted to explore painting without the distraction of trying to sell his art.

“Painting is one thing,” he said, making an emphatic distinction with a knowing smile, “and the art world is another.”

.

Supplies in Athos Zacharias' Studio. Photo by AB photo.

.

He pointed to a large canvas hanging near the top of the stairs as an example of what he said he has been working on for years, the incorporation of Pop art into abstract art. In Zacharias's case, “working on for years” means over six decades, since 1962. Pausing for a few seconds to look at the painting, he said that these days it feels like “I’m getting somewhere.”

As he zigged and zagged around the studio, he shared anecdotes and episodes that illuminated significant way stations of his personal history and the many ways in which that history and the development of his artistic process have been inextricably linked.

.

Athos Zacharias in his studio. Photo by AB photo.

.

After a few years of doing murals with cartoon figures and representational painting in the 1940s, he moved in the 1950s to New York City because he said he “got” what de Kooning and Franz Kline were doing. It moved him and excited him and he wanted to be a part of it.

He talked about the magnetic appeal of the expressionism of Oskar Kokoschka and the early efforts of the abstract expressionists, and then he walked to a counter piled with tools and materials and held up a thick-handled 4-inch brush. “This is the kind of brush de Kooning had me pick up for him when I was his assistant,” he said, laughing. “We were both house painters and he liked to use the big brushes.”

.

Supplies in Athos Zacharias' Studio. Photo by AB photo.

.

He went on to work as an assistant to Elaine de Kooning and then, after Jackson Pollock died, Lee Krasner. He said that working with and watching these artists—and others he befriended, like Grace Hartigan—changed the way he worked. He started out thinking “anybody could do it,” he said, but came to realize that he had to go his own way.

He abandoned the kind of abstraction he saw all around him and went out on his own to explore painting, asking himself, “How can I do something different from what they do but just as exciting?”

“I was always dissatisfied,” Zack said. “Always exploring; trying to understand painting.”

He was always fascinated by the representation of space and depth. “Rembrandt created the illusion of space by triangulation,” he said. “In New York, the abstract painters were working on the denial of illusionistic space; painting was getting flatter and flatter.”

As he continued to study and work out his own path with the suggestion of space and flattening the picture plane, he became enamored of cylindrical geometry, based on the linkage of tiny cylinders in a Rolex watchband. His fascination inspired a 15-year investigation of shape and form in what he calls “the cylinder paintings.”

.

"The World" by Athos Zacharias, 1961. Acrylic, 68 x 80 inches.

.

The process that evolved for these originally hard-edge works started with using a spray gun and fast drying acrylic paints. He later decided to go “inside” the cylinders with rags dipped in paint and additional brushwork, he said, “to bring expressionism back in.”

In the midst of describing the process for the cylinder paintings, Zacharias launched into a discussion of his “window” series, another artistic exploration that lasted for 15 years.

He was drawn to the notion of working with the vertical, the horizontal, the diagonal, and a curve: “That’s the whole vocabulary of composition,” he said. His work with that vocabulary led to his discovery that “the window was a theme, a way in for another direction I could go. The window was a way of beginning.”

Asked why he moved on from cylinders (while retaining them as a structural element) after 15 years, and later moved on from windows after another 15 years, the artist replied, “You mine something and you mine it until you run out of gold, and then you have to look someplace else because you’re obsessed. Crazy, crazy, crazy, but all artists are crazy, right?”

The windows paintings were all in oil. He had to use the slower drying medium, he said, because he needed to take more time to consider what was going on in the work. “I got too involved in the space of the window,” he said. “I had to learn how to compress, because it’s all in your mind and it’s too much to get into a painting.”

.

"Vane" by Athos Zacharias, 1984. 46 x 40 inches.

.

Today, along with more small works—he said he did 50 small paintings in preparation for contributing three to a show opening May 16, 2015 at Silas Marder Gallery—Zacharias is working on a further exploration of the idea that he traces back to a painting he did in 1962.

“It seemed logical,” he said with a shrug, “to try to incorporate Pop into abstract.”

For his more recent large paintings, he started out not even thinking about Pop art. He took a painting and started “editing” it by painting over different parts to see which different abstract forms and figures are the most powerful and evocative.

The editing is how he finds what he wants to do, what speaks to him. He knows the Pop will come in time, he said with a mischievous smile, “because I feel Pop; I feel Poppy.”

To incorporate Pop into the edited abstraction, he has appropriated Basquiat, Lichtenstein, and other artists, along with “stuff I like,” he said. That “stuff” includes: images from the movie “Toy Story” and other cartoons; pictures of actual toys, tools, and airplanes; sometimes art by children and teenagers that he finds on the internet. Anything that touches his playful side or makes him smile.

.

Athos Zacharias in his studio. Photo by AB photo.

.

He starts with pure abstraction. “The freer painting comes first,” he said, “It’s furious, gestural, and complete concentration in the moment, working with abandon.” Then he edits out parts he doesn’t want so that only the most powerful forms remain.

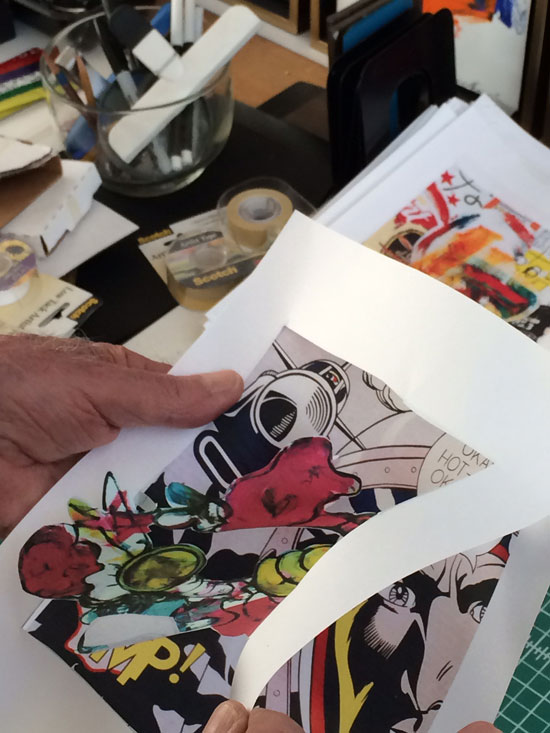

Sometimes he makes small studies from cutouts of abstract compositions overlaid on same-size printouts of appropriated Pop images. These can be used as references for larger works or as prompts for his artistic imagination.

.

Study by Athos Zacharias. Photo by AB photo.

.

Looking back at his 70-year (so far) career in painting, Zacharias said that “while I was doing all this, I didn’t know where I was going with any of it. It takes a very long time for an artist—or for me at any rate—to form yourself.”

“Pure abstraction is pushing paint around and waiting for an accident,” he said, “then taking advantage of the accident. It takes a long time to understand, because intuition is involved and you can’t summon intuition. You can only create the right atmosphere with total concentration.”

“That’s why I have always been exploring,” he said. “Trying to find out.”

He has destroyed many, many paintings over the years. Sometimes he destroyed them because he didn’t have room for them, sometimes because he didn’t understand them at the time. In many cases, he said, he destroyed them simply because “I was always dissatisfied.”

“I am always looking for my style,” he said with another smile as he moved around the studio showing his visitor different paintings of all sizes, dozens of studies, and copious visual notes, along with images on his computer of hundreds of paintings, including many he has destroyed. “Will I ever get there?”

.

Athos Zacharias in his studio. Photo by AB photo.

.

_________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.