Could there be a more exciting conversation starter than the inaugural exhibition at a fresh new museum?

The often rewarding, sometimes exasperating “America Is Hard to See” (the title is a line from a Robert Frost poem) exhibition at the new Whitney Museum of American Art on Gansevoort Street was organized by an in-house team led by Donna de Salvo, chief curator of the museum. It pulls 600 works from the racks, dating from 1900 to an opening-day commission, in a generous survey that mines the museum’s eccentric history. Presiding over the show is the doyenne herself, Gertrude Whitney surveying us like Madame Recamier from her chaise lounge on the first floor in a 1916 portrait by Robert Henri.

.

"Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney" by Robert Henri (1865-1929), 1916. Oil on canvas, 49 15/16 x 72 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Gift of Flora Whitney Miller 86.70.3.

.

The show starts with strength on the eighth floor galleries, especially in a section entitled “Forms Abstracted” where East Hampton bon vivant and underrated Jazz Age artist Gerald Murphy’s Cocktail shares a wall with Stuart Davis’s swinging House and Street.

The Murphy still life was meticulously painted under the watchful eye of Fernand Leger, who had a studio in the garden of Murphy’s Villa America in Antibes and who, along with Picasso, gave the charming American tips on painting. Its precision and boldness harmonize perfectly with the crisp contours of the Davis, and on the wall to their left are two fascinating gouache and ink drawings on paper by Isamu Noguchi, also from the Jazz Age.

The popular favorites on the top floor, as in the old building, are the ever-enchanting Circus of Alexander Calder and the heavyweight champions, paintings by Marsden Hartley and Georgia O’Keeffe as well as Edward Hopper. The curators have oddly chosen to split up the Hoppers in two locations.

.

"Music, Pink and Blue No. 2" by Georgia O'Keeffe, (1887-1986), 1918. Oil on canvas, 35 x 29 15/16 inches.

.

"Early Sunday Morning" by Edward Hopper (1882-1967), 1930. Oil on canvas, 35 3/16 x 60 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 31.426. © Whitney Museum of American Art.

.

Too near the Hopper and the Calder, some media-mad curator has decided to install the first of an absolutely infuriating number of television sets (and yes, there is a corner for Nam June Paik, but that is sculpture and TV sets are just TV sets) whose volume is set just loud enough to intrude on the viewing of everything within three galleries. In this day and age when engineers can pinpoint the acoustics of museum spaces with remarkable accuracy, there is no excuse for this kind of leakage.

The sound on these videos is always absolute crap (maybe Bill Viola, who used the New York Philharmonic for his video works, gets a bye) and it is always adjusted to a level that drives you crazy if you are anywhere nearby, one of the constant sources of headaches at the most nightmarish of the old biennials. More on this curatorial sin in a moment.

One level below the historic highlights, a powerful array of Abstract Expressionist paintings and sculpture are bathed in sunlight on the east side, a particularly wonderful improvement on the old Breuer spaces, with sculpture by David Smith just outside the revolving door on the terrace. A revelation is New York, New York by Hedda Sterne, the only woman in the famous photo of the Irascibles in 1951, tucked ignominiously in a corner but glowering with moody intensity, its palette a nod to the Murnau works of Kandinsky.

One wall boasts a vast and gorgeous painting by Lee Krasner, facing a brilliant room of her husband Jackson Pollock’s works. A vigorous black-and-white Franz Kline glimpsed through the recesses of a Mark di Suvero sculpture in the center of the floor is a lesson in gesture as well as curatorial choice.

Over by a window near the Hudson River is a masterpiece, Arshile Gorky’s The Artist and His Mother, now illuminated for close inspection by sunlight. But not too close, because it is under glass. So is the Murphy painting, by the way, along with a major de Kooning, all the Hoppers and everything by Jasper Johns. What gives?

At the press opening, in the conservation studio that has a glorious floor to ceiling wall of glass on the Hudson (light, light, light), a kind and concerned professional explained: “We have put glass on many paintings for the first few months, because, having learned a lesson from the Tate Modern, we are expecting much larger and much different crowds from the old location, people who do not pay attention to their backpacks or care much about the art.” Once the traffic patterns are analyzed, some of the glass, she promises, will come off.

Another blaring video monitor is way too close to one of the most marvelous moments in the show, the juxtaposition of Jay de Feo’s tragic, haunting and explosive The Rose (which weighs 1,500 pounds) with an untitled Lee Bontecou wall relief whose psychological density is even heavier. The piercing white center of the de Feo is an amazing counterpoint to the absorbing black focal point of the Bontecous. If only somebody would unplug the TV.

.

"The Rose" by Jay de Feo. Photo by Ke Ming Liu.

.

A similar moment of curatorial wit is the conjunction of Johns’s precious White Target and Frank Stella’s Die Fahne Hoch, both awash in sunlight on the sixth floor. Viewers who enter (as I did, thank goodness) from the terrace (having clambered down the steel stairs from the seventh floor) are greeted by Brice Marden’s inviting Garden Table brilliantly lit by sunlight from the east and a smile-inducing answer to the Murphy Cocktail as seen above.

Under the rubric of “Rational Irrationalism” (the section titles seem a bit trite) a corner devoted to Eva Hesse complements the energetic geometries of Richard Serra and a beautifully sited smoked glass box by Larry Bell, over by the window facing east. It will be glorious in the mornings.

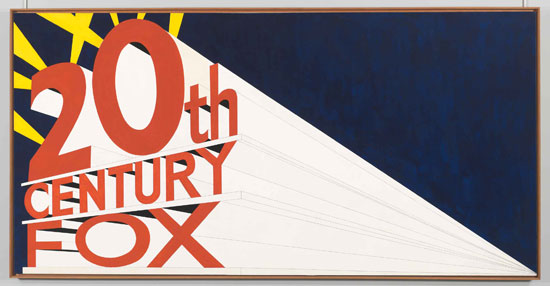

The Whitney is justifiably proud of this opportunity to show off its Pop holdings with major works by Ed Ruscha and Roy Lichtenstein and a perhaps not as impressive range of Warhol paintings, dangled as bait to lure patrons to donate their collections. Meanwhile, another TV is blaring “Bye Bye Love” through its tinny speakers. It’s time to descend.

.

"Large Trademark with Eight Spotlights" by Edward Ruscha (b. 1937), 1962. Oil, house paint, ink and graphite pencil on canvas, 66 15/16 x 133 1/8 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Mrs. Percy Uris Purchase Fund 85.41. © Ed Ruscha.

.

The fifth floor will delight fans of the biennials, while for others it will be a reminder of the rhetorical excesses of the past. Some of the highlights have been unpacked, including a small corner room devoted to Matthew Barney (a poorly concealed utility door looks like it might open and admit a little cloven-hooved Bjork at any moment).

The wall greeting the elevator crowd blares its political message, and the whole gang is here: Kiki Smith, Lorna Simpson, Barbara Kruger, David Hamons, Mike Kelley, Sue Williams. From the human body to the beasts who died so that the meatpackers would have something to get their hooks into (a work by Suzanne Lacy), all the political buttons are pressed.

Some strange moments are presented by the hanging, including sticking vacuous work by the staff favorite Jeff Koons next to Jasper Johns’s genuinely thoughtful Racing Thoughts.

One of the great virtues of the exhibition is the wealth of works on paper it has brought out, including Dorothea Rockburne’s landmark work, Drawing Which Makes Itself with a portfolio by Hans Haacke that satirizes the real estate scene. Aptly enough, over by the west windows a brilliant, flowing blackboard painting made by Cy Twombly in Rome in 1968 seems to empty its poetry straight into the Hudson.

To clear my thoughts for a moment of the chatter on race, gender and politically correct food sourcing, I headed out to the lowest terrace for another glimpse of the city. The space has been given to Mary Heilmann for a site specific installation called Sunset (it faces east) that deploys brightly colored sculptural chairs and vast pink wall, “elements”intended to respond to the staggered planes of the video.

And there, outdoors on the wall, is another damnable TV (playing Swan Song, the artist’s documentary on the destruction of the West Side Highway), its volume set to just that irritating level that my neighbor uses for the TV above his outdoor fire pit (just audible in my garden, but not loud enough for me to know if the Rangers or Penguins are on the power play). As at a sports bar, you can be assured at the new Whitney you will never be far from a screen.

There is no need to pretend the inaugural show is any more epochal than some of the eminently forgettable biennials. Take it as a chance to reacquaint yourself with some of the familiar masterworks and to greet “new” works that have been in storage too long that might disappear for decades again. In time, as the novelty wears off and the glass can be removed from some of the masterworks, the Whitney will settle into its neighborhood and our art viewing habits.

__________________________

BASIC FACTS: “America Is Hard to See,” May 1 to September 27, 2015, the Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York, NY 10014. www.whitney.org.

__________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.