Most of the time, the ears have it at Lincoln Center, not the eyes.

There are onstage visual pleasures, of course, including the lithe beauties of New York City Ballet, the smoldering looks of Latin tenor Roberto Alagna or the prodigious cleavage of Ukrainian soprano Anna Netrebko at the Metropolitan Opera, sets by David Hockney, William Kentridge and photographer and filmmaker JR, but mainly audiences go for the thrill of the music, dance and theater.

But one of the great secrets of the New York art world is a collection that combines cutting edge contemporary with masterworks by Jasper Johns, David Smith, Henry Moore, Marc Chagall, Auguste Rodin and many other major Modernists. It is all hidden in plain view of the public on the campus of Lincoln Center, where latecomers dash by sculpture, paintings and fresh-from-the-studio prints trying not to miss the curtain, blind to the treasures around them.

On the ground floor of the Met Opera building is Gallery Met, a small space usually worth watching that has hosted exhibitions, usually related to the company’s repertory, by such contemporary stars as Chuck Close, Anselm Kiefer, William Kentridge, Julie Mehretu and many others.

On view in this space through May 9 is the puerile “Tribal Frog Tattoo,” paintings apparently whipped up as fast as an art student might work the night before semester’s end by Michael Williams, based on his idea of what Bluebeard’s ink might look like (Bartók's Bluebeard's Castle is one of the new, avant-garde productions).

The show is not without energy. The sunny Slice pops with an eye-straining yellow, the jagged Comb looks like a voice-print for Placido Domingo’s high C, and Tongue has parallel rhythmic channels of acrylic that can, to the opera-obsessed like this writer, suggest the lines of soprano, tenor, mezzo and baritone, but that is a blatant over-reading of a slight and superficial work.

.

"Slice" by Michael Williams, 2014. Acrylic and pencil on canvas, 36 x 40 inches. Courtesy: Michael Williams, Michael Werner Gallery, and CANADA. Photo: Genevieve Hanson.

.

"Comb" by Michael Williams, 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 41 inches. Courtesy: Michael Williams, Michael Werner Gallery, and CANADA. Photo: Genevieve Hanson.

.

"Tongue" by Michael Williams, 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 29 x 38 inches. Courtesy: Michael Williams, Michael Werner Gallery, and CANADA

Photo: Genevieve Hanson.

.

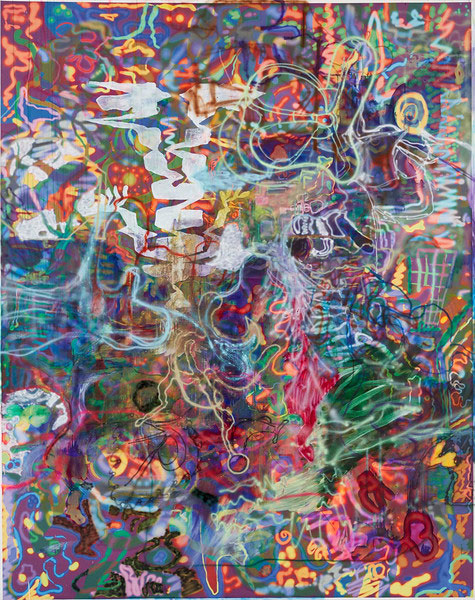

The largest painting by Williams is center-stage on the grand tier level inside the house. Scustin What (maybe an abbreviation of “disgusting,” which seems to this viewer an apt title) is an unchained chromatic fantasy that glows in the middle of the otherwise dignified burgundy grand tier level, mercilessly over-lighted by a pair of Fresnel spotlights.

.

"Scustin What" by Michael Williams, 2015. Inkjet, airbrush, acrylic, oil on canvas, 98.5 x 78 inches. Courtesy: Michael Williams, Michael Werner Gallery, and CANADA. Photo: Genevieve Hanson.

.

It is not quite the ugliest work of art in the opera house, a distinction that would have to go to the spectacularly awful bronze contraption gathering dust over the proscenium by an artist who should remain nameless, but whose initials fit the name Mary Callery. An early guidebook described it as “an untitled ensemble of bronze forms creating a bouquet of sculptured arabesques above.” When I wrote the official history of the art and prints at Lincoln Center, it was the one and only item I purposefully left out of the book.

Why dwell on the notes that fall flat when there are so many glorious highlights not just in the opera house, but all around the Lincoln Center campus? Almost everywhere one looks, in corridors or by water fountains and ticket windows, there are prints by a dazzling roster of contemporary artists commissioned since the 1960s by the List Art Project. In its day, the project was an innovative fund-raising initiative that has enlisted the talents of Robert Motherwell, Andy Warhol, Chuck Close, Ben Schonzeit, Howard Hodgkin, Helen Frankenthaler, Donald Sultan and many others to create a limited edition print (whose values have soared over the decades) that are also used for posters.

Every year fresh and genuinely wonderful prints are released, including terrific new editions by Angel Otero and Sarah Morris. The print program offers the visitor the opportunity to buy a little piece of Lincoln Center at a vastly more reasonable price than the $100 million David Geffen bid for the naming rights "in perpetuity" to what has been known up to now as Avery Fisher Hall, another philanthropic travesty in the name of money. A selection of the prints is on view in a gallery located on the concourse level of the hall that will bear Geffen’s name starting in September of this year.

.

"Untitled (SK-PH)" by Angel Otero. Courtesy Lincoln Center Vera List Art Project.

.

"Total Lunar Eclipse Rio" by Sarah Morris. Courtesy Lincoln Center Vera List Art Project.

.

In addition to the contemporary presence of prints and the Gallery Met, the permanent collection of Lincoln Center, acquired by a committee that was luckily bullied by architect Philip Johnson into collecting his friends, is worth a tour for those who arrive well before curtain time. From the plaza there is an excellent view of the exuberant Marc Chagall paintings (not murals), commissioned for the opening of the new Met in 1966.

The Met was the only opera house in the world that had a set design by Chagall, for his beloved “Magic Flute” by Mozart. He used a bright red tonic note for The Triumph of Music (1966), in reference to the Firebird of his compatriots Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Diaghilev, and a blast of gold for The Sources of Music (1966), with its allusions to King David, wearing his crown, and Orpheus with his lyre at its center surrounded by portraits of Wagner and Bach, and Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde embracing.

An amusing secret: He planned the red panel to hang on the north side, the gold on the south. He arrived after the installation and had a fit, but Rudolf Bing, the manager of the opera, calmed him down.

Inside the Met, voluptuous nudes by Aristide Maillol are joined by the skinny Kneeling Woman (1911) by Chagall’s German contemporary, the Expressionist master Wilhelm Lehmbruck. Down by where the swells swill their champagne and check their furs, one of the (too stiff) portraits of the great singers is a huge resin and oil Julian Schnabel painting of Placido Domingo.

In the lobby of the Koch Theater the heavy glass plate protecting Numbers (1964) by Jasper Johns attests to its market value. Johns was still a relative unknown when Lincoln Center commissioned this piece at the urging of Johnson, who designed the building. Its quiet grey-on-grey layers build a steady rhythmic etude on the most basic of thematic ideas: The footprint in the upper left hand corner was made by Merce Cunningham, master choreographer and frequent collaborator with his friend Johns as well as the artist Robert Rauschenberg.

The unsung masterpiece in the lobby is Untitled Relief (1964) by Lee Bontecou. This massive work, supported by a framework she welded and the largest she ever made, is in the eyes of many her most important piece.

Across the plaza in what (for now) is still called Avery Fisher Hall, the sun glints from the golden bars of Richard Lippold’s Orpheus and Apollo (1962). Below it is one of the most important masterworks in the collection, David Smith’s Zig IV (1961).

This work uses Smith’s signature idiom of industrial steel parts welded by him into a carefully choreographed unity, its surface an outstanding example of Abstract Expressionist painting, a reminder of Smith’s gifts with the brush as well as the torch. It shares the space with Rodin’s Bust of Gustav Mahler (1909-1910) bringing together two of the soaring talents of their times.

Just outside in the reflecting pool beside the Met is the dramatic high point of the Lincoln Center collection, Henry Moore’s immense Reclining Figure (1962-1965).

The visitor’s gaze is so firmly held by the Moore that it is easy to miss a shadowy “stabile” by Alexander Calder playfully titled Le Guichet (1963). The title is French slang for “box office,” and one of the pleasures afforded by the Calder, not encouraged by the Moore sculpture, is the ability to wander in and through its spider-like apertures, looking up at the blue sky and marveling not only at the way Calder cut these graceful forms from plates of steel (as easily, it would appear, as Matisse cut out paper forms), but at the lively way in which they are assembled.

For a surprise, just past the Calder in the New York Public Library, in a back corner of the Frank Sinatra memorabilia exhibition on view through September 4, there is a mock-up of the crooner’s California painting studio with a selection of “cover” versions of Jawlensky, Kandinsky and Klee. These may not be as technically memorable as Chagall or Johns, but they could be worth a few points in a trivia contest.

_________________________________

Charles A. Riley II is the author of “Art at Lincoln Center” (Wiley), the officially commissioned history of the collection and Vera List Art Project.

_________________________________

BASIC FACTS: Lincoln Center is located at 10 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023. For more information on the Vera List Art Project at Lincoln Center, visit www.art.lincolncenter.org.

The Metropolitan Opera is located at 30 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023. www.metopera.org.

_________________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.