War is in the air and it’s picking up tailwinds, which makes the recent Louvre-Lens’s show in France, “The Disaster of War 1800-1914”, less a history lesson and more a cautionary tale.

The show, which closed October 6, 2014 took its title from Goya’s print series about how warring between France and Spain put humanity in a chokehold. The Louvre-Lens show went further. It also recounted the change in the way artists pictured war after Goya. Exhibition examples clearly illustrate the shift from artists viewing war as heroic to seeing armed conflict as horrific.

Heroism was the look of war in the 1800s. In Napoleon Crossing the Alps, Jacques-Louis David painted the French military leader on a white horse—the image of the white knight on white mount of fairy tale lore.

.

"Napoleon Crossing the Alps" or "Bonaparte at the St Bernard Pass" by Jacques-Louis David, 1800-1. Oil on canvas, 102 x 87 inches. Chateau de Malmaison, Rueil-Malmaison. From Smarthistory.org.

.

Less than two decades later, the image of glory in battle did an about-face. You can see it in The Return From Russia, a lithograph by Théodore Géricault depicting the effect of Bonaparte’s militarism: drained and disabled soldiers.

.

"The Return from Russia" by Jean Louis André Théodore Géricault, 1818. Lithograph in black with tan tint stone on ivory wove paper, 444 x 361 mm. Albert H. Wolf Memorial Collection. Image from the Art Institute of Chicago's website.

.

The Louvre-Lens show brings to mind the way that American artists in the 20th century changed their take on war over time. One might start with sculptor Felix Deweldon's triumphant monument of World War II in 1954—five marines and a Navy corpsman raising the flag on Iwo Jima—located outside Arlington National Cemetery.

.

"Marine Corps War Memorial (Iwo Jima)" by Felix W de Weldon. Image from dcmemorials.com.

.

Nearby stands a different kind of tribute, this one installed in 1982, to the Vietnam War—Maya Ying Lin's long black granite wall, half-interred in the earth with its engraved roll call of the dead or missing.

.

"The Vietnam Veterans Memorial" by Maya Ling Yin. Image from culturedart.blogspot.com.

.

The contrast between the two shrines is more than form. It shows a shift in our way of thinking about war. These artists’ words about their work also make the point. Deweldon saw his work as a "symbol of our freedom"; Lin saw hers as a symbol of the cost of freedom: "I had an impulse to cut open the earth, an initial violence that in time would heal. The grass would grow back, but the cut would remain."

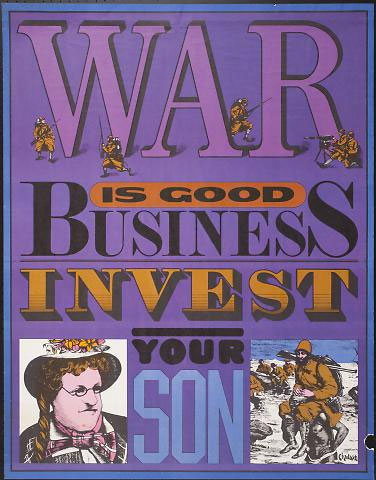

Lin’s focus on the violence of war could be seen in the ’60s when artists wielding loaded brushes attacked the military machine. Seymour Chwast’s 1967 poster “War is good business. Invest your son'' suggested that war is a good bet for the economy. And Faith Ringgold’s 1964 painting God Bless America of a drained-face woman, wearing the Defense Department bluestar that indicates a family member in service, set behind the stripes of the U.S. flag as if they were penitentiary bars.

.

"War is Good Business, Invest Your Son" by Seymour Chwast, 1967. Offset Lithograph Paper. All Of Us Or None Archive at The Oakland Museum of California. Fractional and promised gift of The Rossman Family. From the OMCA website.

.

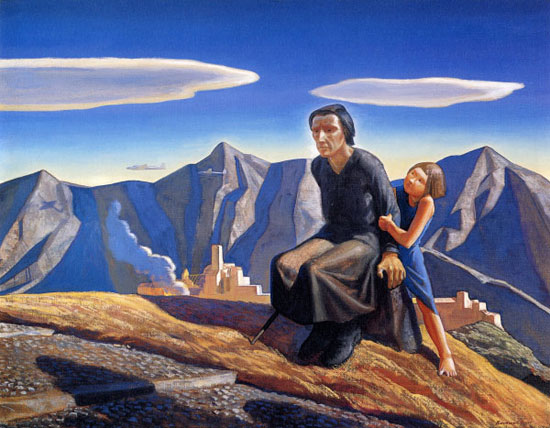

Not that artists’ anti-war sentiment even began in the ’60s. You can see how triumph gave way to tragedy in a 1942 painting by Rockwell Kent called Bombs Away that shows a woman sitting in a field of exploding bombs. Or Leonard Baskin's 1954 woodcut Hydrogen Man that frames up the Cold War of the ’50s with a nude figure cut down to a shredded lump.

.

"Bombs Away" by Rockwell Kent, 1942. Image from Artandsocialissues.cmaohio.org.

.

Decimation was certainly the theme in the ’80s when Lin’s Vietnam War Memorial was erected. You could read the signs in fiction and nonfiction as well as in fine art. George MacDonald Fraser's 1988 pointed history of movies, “The Hollywood History of the World,” made clear that bloodshed was an everyday occurrence in America's cities. As he put it: "It seems to me possible the 20th century may be regarded by posterity as the time when the civilized nations of the earth began to commit suicide."

Bill Charmatz's ink drawing Duet in the ’90s caught up with Fraser’s thought by showing two foes shooting each other simultaneously. Apathy seemed the theme in American art in the ’90s. Jean Rustin's painting Father, Mother and Son, with its expressionless figures staring out like concentration camp captives, tells that story.

And some artists of the 21st century have picked up the story without ever referring to war. I’m thinking of multi-media artist Rina Banejee’s show at L.A. Louvre in Venice, California, in May of this year, called “Disgust.”

On the museum website, she contended that “Disgust” is about women: “a way of thinking about what is so clear in our emotional response that it forms a boundary … those boundaries are sometimes what we play with in terms of our cultural orientation.”

But the title of one work alone—All these organs so too the oral and anal, and nasal, drops and globs like snail, slug, slip and slide, dissolve all our strength—brings to mind the current horrors in Afghanistan, in the Middle East, in Syria, not to mention all the mayhem from ISIS. And it’s impossible not to think about the constant battles and bloodshed.

Then there’s Eric Fischl’s Tumbling Woman, an overturned, flailing nude that he sculpted a year after the World Trade Center disaster to signify those who jumped to their death from the 110-story towers. Onlookers were so upset at the sight of it in Rockefeller center that it was removed from view by public demand.

.

"Tumbling Woman" by Eric Fischl, 2002. Bronze, 37 x 74 x 50 inches.

.

Apparently, the world is so weary of the constant death and destruction that it needs to run from it, not unlike the way Monet did during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 when, clearly affected by the conflict, he escaped to London to paint parks.

And American artists have gone from commemorating the heroism of the military with works like Deweldon's WWII memorial in 1954 to pieces like Fischl’s Tumbling Woman, with its focus on the suffering of innocent civilians.