The textile arts and their constituent mediums—sewing, knitting and weaving—have been in the spotlight this season, with major shows that illuminate their broad margins and historic breadth.

Not so long ago, the “fiber arts” were routinely dismissed as a subset of the craft tradition, deemed not so much unworthy of, but extraneous to contemporary art. Things have changed in some five decades and a handful of current exhibitions celebrate all manner of filament, threads, strings and things drawn from varying textile/fiber tropes and methodologies.

At Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, senior curator Jenelle Porter organized an overview of the fiber arts since 1974 in “Fiber: Sculpture 1960-present,” on view through January 4, 2015. In New York, The Drawing Center presents “Thread Lines,” a natty selection of historic and contemporary textile and textile-like works from an international pool of artists. And at Silas Marder Gallery in Bridgehampton, Louise Eastman pulls out all the stops in Loop Holes, the artist’s first one-person exhibition at the gallery. Curated by Jess Frost, the show features Eastman’s signature “potholders”: large-scale squares of crisscrossed color in sundry materials including knit, felt, toilet paper (yes, toilet paper) and masking tape.

Wooly Wooly

At Silas Marder, Eastman’s work bounces from kitschy excess to the meditative, with weaving at the center of it all. Using a hand-crank knitting machine, she produces lengths of knit tubing, looping them on a rudimentary loom into networks of woven color and textures. Plush and elastic like the childhood potholders we made from dime store kits, Eastman’s pieces trade on the portent of the grid to create a floppy geometry of loose ends and all over composition.

.

"Potholder I" by Louise Eastman, 2014. Wool and acrylic wool, 78 x 78 inches. Photo by Serry Park.

.

In Potholder II, skeins of wool and felt strips fuse into a riot of color. Bright greens, orange, red and blue are punctuated by broken lines of white and sloppy knots that tie off the square ends. With a few errant strings dangling below, everything commingles to joyful effect. A number of ceramic bricks, each one possessed of an expressive, pigment-saturated glaze, function like component parts of a massive, altogether separate, three-dimensional grid.

.

"Potholder II" by Louise Eastman, 2014. Wool and felt, 78 x 78 inches. Photo by Serry Park.

.

But the artist’s site-specific installation, Loop Holes, a conflagration of wool tubes and tape, felt and stringy bits, is true knit-bliss. A gleeful miasma of lines and twists and knots of color, the structure mounts the stairs and balcony, loosely knitting a helter-skelter scaffolding that seems to emanate from an oversize yet unassuming yarn ball nearby. Prismatic and sumptuously haywire, the net result is this side of euphoria.

.

"Loop Holes" by Louise Eastman, 2014. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo courtesy Silas Marder Gallery.

.

Thread Lightly

Back at ground level, The Drawing Center’s “Thread Lines” in New York offers an examination of 16 artists whose works revolve around filament and the idea of line in varied techniques and materials that include drawing, stitching, knitting, embroidery and performance. Organized by assistant curator Joanna Kleinberg Romanow, at its aesthetic heart the show begins with Lenore Tawney, whose trailblazing experiments first helped to identify the very idiom, fiber art.

When she abandoned sculpture in 1954, Lenore Tawney turned to weaving, taking function out of the medium and replacing it with visionary, improvisational works that sometimes grew to room-size. The two modest works on view hardly elucidate the groundbreaking nature of her contribution to the arts, but in Union of Water and Fire, 1974, a hint of the artist’s line-based objects and woven forms begins to emerge. Complex and shield-like, the crisscrossing color bands offer a glimpse of Tawney’s later work with strings.

.

"Union of Water and Fire" by Lenore Tawney, 1974. Linen, 38 x 36 inches. Collection of Lenore G. Tawney Foundation.

.

In the 1940s Tawney studied with László Moholy-Nagy and Alexander Archipenko at Chicago’s Institute of Design, later working at Penland School of Crafts in North Carolina with Finnish weaver Martta Taipale. She moved to New York’s Coenties Slip in 1957, a community of post-abstract expressionists that included Agnes Martin, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Indiana and Jack Youngerman. Tawney was a dissident among dissidents in this, a coterie of artists whose early work would move the dialogue of abstract expressionism toward a new language.

Similarly, Sheila Hicks broke ground with a studio practice that merged painting, drawing, sculpture and the woven form with architectural-scaled, site-specific installations. A student of Josef Albers and George Kubler, early in her development Hicks was exposed to ancient weaving techniques in Chile, where she traveled in 1957 on a Fulbright scholarship. Having embraced a “thread consciousness” gleaned from her mother and grandmother, Hicks took to fiber almost immediately. In the six small weavings on view, her inventiveness and inquisitive flair is evident.

.

"Punched Notations" by Sheila Hicks, 2012. Paper and synthetic yarn, 9 1/2 x 7 1/2 inches. Andrea and José Olympio Pereira Collection.

.

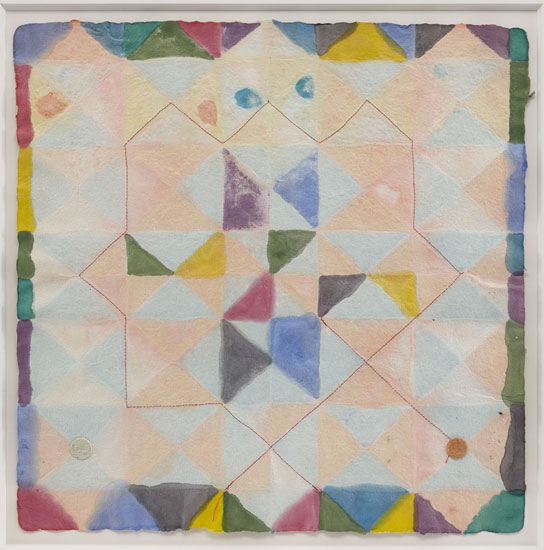

Like Hicks, Alan Shields learned to sew on the family farm, from his mother and sisters. He utilized his sewing machine prowess to eye-popping effect in post-minimalist paintings, prints, constructions and installations that bent every rule in the book. Tie-dyed, beaded, stenciled, punctured, pulled apart and reassembled, Shields’s work was the psychedelic equivalent of Hieronymus Bosch meets Penn & Teller. Not Too Risky, 1973, is a collision of watercolor, appliqué and the artist’s signature stitchery on thick, handmade paper.

.

"Colors in Clay" by Alan Shields,1988. Watercolor, stitching on handmade paper, 18 x 18 inches. Courtesy of the Estate and Van Doren Waxter.

.

Fabric drawings by Louise Bourgeois integrate the artist’s autobiographical locus with allegory and memory conjured from working in the family tapestry shop as a child. In three untitled works, the artist’s manipulation of textiles and stitchery convey parasol interiors and spider webs. The webs represented a consistent theme for the artist, who portrayed her mother as a spider in drawings, fiber works and sculpture throughout a career spanning seven decades.

.

"Untitled" by Louise Bourgeois, 2006. Fabric, 15 x 22 1/4 inches. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York © The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

.

Among the list of innovators in the group above, the curator also includes Elaine Reicheck’s mythological samplers, Beryl Korot’s technology based textile works, and complex embroidery in book-form by Maria Lai. As pioneers in this genre, these seven artists laid the groundwork for Kleinberg Romanow’s exhibition seeking to illuminate the potential of line in both drawing and textile based works and in the work of the nine younger artists on view.

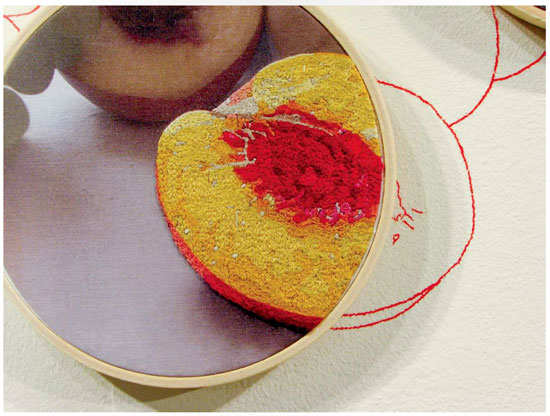

In this regard, two artists stand out. Across the width of the main gallery’s rear wall, the Chilean artist Mónica Bengoa’s cross-stitched fruits and vegetables are part line drawing and part exquisite embroidery. The needlework, cinched inside embroidery hoops, is breathtaking, with masterful articulations in color and form that dot the larger drawing field depicting a modernist cornucopia.

.

"One Hundred and Sixty Three Shades of Yellow, Green, Orange, Red, Purple, Brown, Gray and Blue (so far)" by Mónica Bengoa, 2005-14. Wall drawing and hand-made embroideries on photographic transfer on cotton cloth. Dimensions variable (originally installed at Artspace, Sydney, Australia). Courtesy of the artist and Collection of Jorge Bustos. Image from The Drawing Center's online catalogue.

.

"One Hundred and Sixty Three Shades of Yellow, Green, Orange, Red, Purple, Brown, Gray and Blue (so far)" by Mónica Bengoa, 2005-14. Wall drawing and hand-made embroideries on photographic transfer on cotton cloth. Dimensions variable (originally installed at Artspace, Sydney, Australia). Courtesy of the artist and Collection of Jorge Bustos. Image by JMGoleas.

.

Anne Wilson’s To Cross (Walking New York) is the result of an ongoing, on-site performance in which participants replicate the actions of a loom by slowly and systematically unfurling a spool of thread around the four structural columns in the main gallery. Where thousands of lines intersect in the center, a dizzying crisscross of parallel lines creates a pulsing optical field, effecting something of an homage to Lenore Tawney’s Cloud Series. The installation will continue in its development through November 2.

.

!["To Cross (Walking New York) [Thread Cross Research]" by Anne Wilson, 2014. "To Cross (Walking New York) [Thread Cross Research]" by Anne Wilson, 2014. Site specific performance and sculpture. Courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery. Photo by JMGoleas.](https://hamptonsarthub.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/WEB_get-attachment-5.jpg)

"To Cross (Walking New York) [Thread Cross Research]" by Anne Wilson, 2014. Site specific performance and sculpture. Courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery. Photo by JMGoleas.

.

!["To Cross (Walking New York) [Thread Cross Research]" by Anne Wilson, 2014. "To Cross (Walking New York) [Thread Cross Research]" by Anne Wilson, 2014. Site specific performance and sculpture. Courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery. Photo by JMGoleas.](https://hamptonsarthub.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/WEB_get-attachment-6.jpg)

"To Cross (Walking New York) [Thread Cross Research]" by Anne Wilson, 2014. Site specific performance and sculpture. Courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery. Photo by JMGoleas.

.

Other standout works include Drew Shiflett’s constructed drawing Untitled #66, 2012 a rippling expanse of handmade paper inscribed with a network of fine lines that accumulate across its broad surface. Byzantine and intricate, Shiflett’s layered imagery coalesces slowly, like thousands of minions marching toward a horizon.

.

"Untitled #66" by Drew Shiflett, 2012. Watercolor, graphite, Conte crayon, handmade paper, cheesecloth, 53 1/4 x 60 x 2 1/2 inches.

.

Working within a tenet similarly acquainted with the obsessive, Sam Moyer unravels IKEA throw rugs, disassembling the warp and weft until only a gridded skeleton remains. With a revisionist’s eye, she then reassembles them in a wholly new format, coats them with black encaustic and hangs them in box frames. Like a colonialist, Moyer’s act is political in nature, preserving the physicality of the rugs but stripping them of their origins.

.

"Worry Rug 4" by Sam Moyer, 2009. IKEA rug, encaustic, 47 x 28 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery. Image from The Drawing Center's online catalogue.

.

For South Korean artist Kimsooja, the indigenous cultural traditions in weaving and other forms of textile construction are depicted in an ongoing film project titled Thread Routes.

In Chapter 1, the artist examines Peruvian weaving as it exists today in the highlands of Machu Picchu, nearly unchanged from its ancient past in technique or materials. The footage is a nuanced patchwork of women hand-spinning fibers into threads, weaving with looms and creating textile designs juxtaposed with vistas of mountains, farmlands and local housing. The film offers a poetic glimpse at the power and permanence of the creative act. With a focus on linear mark-making, the show covers a wide swath of contemporary practices, processes and precedents.

Beantown

Admittedly, I’ve yet to get up to Boston to see “Fiber: Sculpture 1960-present” firsthand, but it is arguably the mother lode of textile/fiber arts exhibitions—certainly this season. Wherever you call home, this is a trip worth taking.

ICA (The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston) has lately been consistent in mounting brilliant and thoughtful exhibitions one after another, including must-see shows by Amy Sillman, Nick Cave and, opening November 19, the first solo museum show of the complex Brazilian artist Adriana Varejão.

By all accounts, “Fiber” is also an A-list show, the first of its kind in 40 years, with 34 artists altogether and major works by Eva Hesse, Françoise Grossen, Ernesto Neto, Faith Wilding, Lenore Tawney and Sheila Hicks.

.

"Ennead" by Eva Hesse, 1966. Acrylic, papier mâché, plastic, plywood, & string, 96 x 39 x 17 inches. Collection of Barbara Lee, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Photo by Abby Robinson, © The Estate of Eva Hesse, courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

.

BASIC INFO: “Thread Lines” remains on view through December 4, 2015. The Drawing Center is located at 35 Wooster Street, New York, NY 10013. www.drawingcenter.org.

“Louise Eastman, Loop Holes” was extended to remain on view through November 16, 2014. Silas Marder Gallery is located at 120 Snake Hollow Road, Bridgehampton, NY 11932. www.silasmarder.com.

“Fiber: Sculpture 1960-present” remains on view through January 4, 2015. The Institute of Contemporary Art is located at 100 Northern Avenue, Boston, MA 02210. www.icaboston.org.

________________________________

Copyright 2014 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.