Performance art has always sought to unite extremes.

In 1921, when Marcel Duchamp cross-dressed as the female vixen Rose Sélavy and became his own work of art, he created what is arguably the first piece of performance art. Ever since, in one form or another, performance art has played with boundaries: between artist and viewer, motion and stillness, imagination and reality, and, at the Watermill Center’s 20th anniversary benefit this year, the membrane between the domains of heaven and hell. For one evening, on July 27, 2013, those polar realms merged and inhabited the same territory: “Devil’s Heaven.”

Off the beaten track of the Hamptons summer scene, hidden among trees and ornamental grass, the Watermill Center is a unique laboratory for performance and installation art. Each summer, founder Robert Wilson invites 60-80 emerging artists from more than 25 countries for a four-week collaborative residency program, giving them time to work, live, and create amid the compound’s landscaped paradise and its rich collection of art and artifacts. Performances are ongoing at Watermill throughout the year, but the highlight of the season is the always spectacular, always decadent benefit that raises the funds needed to sustain the Center.

As twilight encroached, a fog of white smoke billowed across the formal entrance as guests, sipping a devil’s brew of rum and cherries, passed under two naked, entwined figures painted by the artist Trina Merry to resemble a magnolia tree. Merry is becoming known for her use of the human body as template and canvas. Many of her living installation pieces dotted the evening's landscape.

Climbing a simple, gradated staircase that evoked the majesty of an ancient temple, guests then proceeded under Angel’s Landing, a 23-by-24-foot photographic tapestry by John Messinger. Conjuring the rich orange and red colors of the majestic rock formation of the same name in Zion National Park—where legend has it that only angels dared to land—Messinger has composed 5,940 individual instamatic rectangular images into one huge shifting, shimmering tapestry.

Further on, visitors were treated to a ride on Robert Wilson’s Stargazer Beds, six metal and wood platforms spaced in the central courtyard. Once positioned aboard in a prone position, visitors were hoisted heavenward by a young attendant manning a rope. The experience brought home, on a concrete and visceral level, the notion that only by releasing control and trusting oneself into another’s hands can one truly experience something new. That notion is what all art requires.

At heart, Robert Wilson is a storyteller. His benefits are more than just fundraisers for the art world elite: they are examples of his operatic sense of narrative structure and sweeping adventures incorporating large casts of characters in grand tableaux. Each is thematic and this year’s extraordinary event was organized around the visions of two unique artists: Dieter Meier and Clementine Hunter.

Meier and Hunter could not be further apart in background. Born on a Plantation in Louisiana, Hunter was the African-American illiterate granddaughter of a slave. Self-taught with oils left behind on the plantation where she lived, Hunter didn’t begin to produce art until she was in her mid-50s and then only sold her small paintings for 25 cents apiece at the local five and dime. When Wilson was only 12 years old, he visited the plantation where Hunter worked and she became the first artist he ever met, her work the first he ever purchased.

By contrast, Meier is a millionaire Swiss polymath, a man who indulges in everything from professional poker, industrial entrepreneurship and filmmaking to the role of lead singer in the electro-pop band Yello and performance artist.

What unites Hunter and Meier, and all the installations and performance pieces at Watermill’s Devil’s Heaven, is a dedication to exploration and the idea that art can not only incorporate any material and exist in any place, but it can spring from any one of us, from the least educated to the most cultured.

As tribute to Hunter’s unaffected brilliance and determination, the central courtyard of the Watermill Center was given over to a replication of African House. This was a food storage bin on the grounds of the plantation where Hunter lived out her life. Hunter covered the walls of the tiny room with murals depicting scenes of plantation life, even though she had never seen a mural before. Using bright folk-like colors, she painted from memory scenes of spring planting, wash day, weddings, funerals and baptisms, as well as images of household items like jugs of flowers. Her small canvases, no bigger than 18 by 24 inches, are both bold and delicate, communicating a resilient personality, a woman able to transmute the hardscrabble reality of her life into objects of transcendent beauty.

Off to one side of the African House was another homage to Hunter. Robert Wilson, along with the artists Sophie Beck, Giovanni Firpo and Zarchary Schoenhut staged "Clementine Hunter’s World," a musical reenactment of scenes from Hunter’s plantation life.

Outside of the Africa House. Courtesy Watermill Center.

Inside of the Africa House. Courtesy Watermill Center.

Like so many journeys, the one at Watermill involved a crossing through darkness into light. So, leaving behind the Stargazer Beds and African House in the courtyard, guests entered the woods. The next encounter was Lisa Lozano's Funérailles de Miel. This was a gruesome vat in which the naked Lozano lay submerged in a gory goop of …blood? Was this a crime scene?

But wait, a woman in black stood off to the side gesturing to a nearby table laid with rows of silver dessert spoons. Ah, we were meant to sample this macabre feast! As I dipped my spoon I couldn’t help but recall that memorable line from "Silence of the Lambs" when Hannibal Lecture quips, “I ate his liver with some fava beans and a nice chianti.” The liquid surrounding Lozano turned out to be rich honey-flavored molasses, which, if I knew French, I would have guessed from the title, which translates to "Funeral of Honey."

“The truth is revealed only when others interact with it,” Lozano has stated. “It is lifeless without the viewer.” To Lozano, truth is also apparently imbued with sweet, ghoulish irony.

As the path wound through the trees (often bedecked with naked figures painted by Merry to resemble bark and vines) performance pieces were alternately obscured and then revealed. As in life, and stories, one couldn’t see around the bend. The next encounter was a delightful dancing celebration—another tribute—Clementine Hunter in Devil’s Heaven. This was a visual re-creation of one of Hunter’s paintings of red and white dancing angels.

Further on, viewers were greeted by an assemblage of cooing celestial beings positioned in front of organ pipes made out of what looked like Dan Flavin lights. This was Amnesia, the work of artist Dilek Acay, with the ground shaking under the feet of visitors standing amid their regal ranks.

Then more nude tree spirits, then a giant green howling man with a stick, then a site of embedded videos until we came to a wooden stage where a man with the head of a metal funnel was being fed by two waiters clad in dress-whites, their faces painted in white-face, their lips, huge, red and full. This was Yao Zhang’s My Favorite Food, and the meal was soap. It brought to mind a child having his or her mouth washed out, though this time what was produced were not howls of distaste, but glistening, iridescent soap bubbles.

The journey was not over. Off the stage visitors plunged back into the woods where a performer clad in a darkly sinister get-up of a harness with a clear plastic bag over his head was chained by a rope to a stake in the ground. The Whelping Box, a collaboration by artists Matthew Prest, Branch Nebula and Clare Britton, personified the struggle of man against nature. The tethered performer struggling against his stake could be seen as an ominous warning in the form of a pun, perhaps, about the perils of staking a claim in the art terrain and the struggle to overcome the constraints and suffocation of being tied to one kind of expression or label as an artist?

Finally, the last stop in the woods presented a tragedy, the moment in any journey when redemption seems unattainable. This desolation was perfectly illustrated by the exquisitely austere performance of Evangelia Rantou. Solo with Chairs from Medea (2) is a silent telling with dance created by the avant-garde stage director and choreographer Dimitris Papaioannou. Elegant and wretched Medea, her movements slowed by grief, is isolated in a black pool of water. Rantou expertly portrayed the rise and fall of the savagery of Medea’s anger, as, secluded in her dark reflecting pool, the depth of her drama is stretched to infinity.

Central to the Watermill benefit is the art auction and central to this year’s art auction was another performance piece, Trina Merry’s Objectified: six naked people airbrushed to resemble modern furniture. Blending in with their surroundings, the painted models shape-shifted, forming and reforming a sleek human lamp, a colorful crowded fruit bowl, a slightly overstuffed, comfy chair, and a crouched, exposed glass table, all while viewers entered and in some cases interacted with the living tableaux.

Downstairs—slightly outlier in nature and location like Watermill Center itself—was an exhibit that in many ways felt like the foundation for many of the performances going on in the woods: Dieter Meier and the Yello Years, curated by Harald Falckenberg and Tony Guerrero.

Perhaps it is in his role of performance artist that Meier best expresses the multifaceted nature of his various identities. But for such an accomplished man—Meier is known mostly in the United States for his music, which has been heard in films like "Ferris Bueller’s Day Off" and "The Secret of My Success"—Meier’s art struck me as darkly ironic and focused on the tenuous quality of identity and the certainty of failure. This dark irony is underscored by the fact that his status as a millionaire has allowed his exploration of failure.

Meier is president of the Association des Maitres de Rien (Association of the Masters of Nothingness), a gathering of artists devoted to the realization of insignificance. His manifesto, Des Maîtres de Rien from 2007, reads: “Man is a senseless coincidence who circles a sun like a piece of intergalactic driftwood for a fraction of a cosmic second, desperately struggling to make sense of the nonsense between birth and death.”

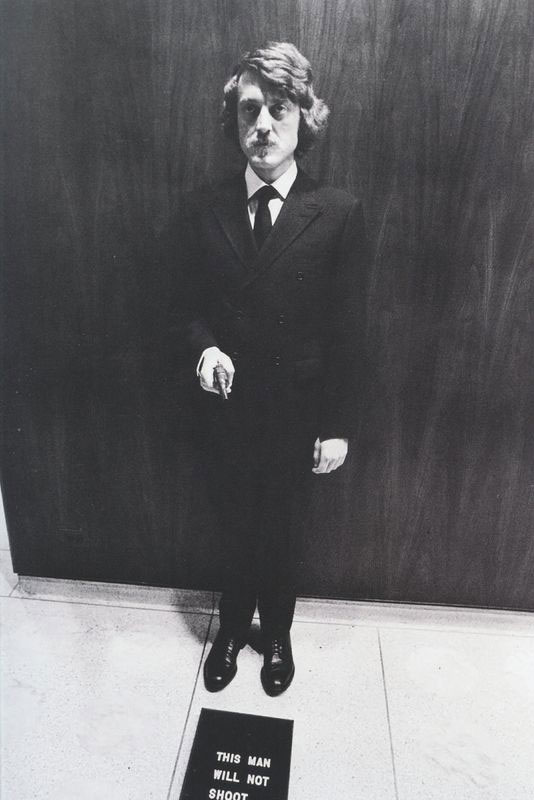

Beginning in 1969 (at age 24) with 5 days, Meier’s work was already centered on futility. A plaque and photograph tells the viewer that in a public square, during 5 days, from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Dieter Meier counted 100,000 pieces of metal and put them into 100 bags of 1,000 pieces each. A few years later, in 1971 he created, This Man Will Not Shoot. In this performance, Meier stood in the entrance to the New York Cultural Center with a revolver in his hands and a notice that read, “This man will not shoot.” Wouldn’t, and couldn't, happen these days, but the early '70s were a time when the art world was rife with extreme and enigmatic provocateurs.

Six months after Meier’s piece, an artist named Chris Burden pulled the trigger. In Shoot performed in Santa Ana, California, Burden had his assistant fire a .22 caliber rifle into his arm. Anything seemed possible. And maybe that’s Meier’s message: things are as possible as they are ephemeral. By 1973 Meier had begun experimenting with invented characters. In one piece, Oskar Lips, an invented name appeared on an empty page in a daily newspaper. Slowly, Meier, like Cindy Sherman a few years later, was becoming his sculptures.

One of the highlights of this exhibition is a hilarious series titled, Accidental Births. First begun in 1977, these are photographs of tiny faces and figures in conversation that Meier created with children’s modeling clay while he was waiting on the phone or bored. Like Hunter and many performance artists, Meier uses whatever materials—even himself—that is easily at hand.

Meier has said that the images in Accidental Births, like many of the works in his oeuvre, are not meant to express anything. But as Meier knows, audiences can’t help but read expression into the perplexing, fleeting creations. And he has titled each with phrases that came to mind after their creation. One reads, “What else could I expect” another “You didn’t expect me to come back, but here I am.” True to the fleeting nature of his work, and to the ephemeral quality of emotion itself, each of these pieces was photographed and then immediately destroyed.

"What else could I expect?" by Claire Saymour-Wang. From "Accidental Birth" , 2010-2013. Courtesy Watermill Center.

Genius or madman or perhaps both, Meier is a master of the transitory art of performance. Like Marcel Duchamp, the great granddaddy of the art form, Meier believes that the importance of art lies in its ability to incarnate experience, even banal experience. But it is just this exquisite focus on capturing the moment that creates the stuff of art. Insignificant occasions like washing day on a plantation, as Hunter’s paintings illustrate, or a day Meier decided to jump in the air and capture his action in a photograph, these too, mutate into art.

The magic of performance art is that it allows visitors to enter into this brief instant of creation alongside the artist, to watch and participate as they transform themselves into works of art and inhabit a space that is full of possibility.

BASIC FACTS: "Deiter Meier and the Yello Years" and "African House - Clementine Hunter" remains on view through September 1. The exhibition is open Thursdays through Saturdays from 4 to 7 p.m. or by appointment by contacting Kirstin Kapustik at 631.726.4628.

Suggested donation is $20 for adults and $10 for students.

Many of the art performances will be presented on Sunday (August 11) from 3 to 6 p.m. during Discover Watermill. The open house event is free and open to the public. No reservations are necessary.

The Watermill Center is located at 39 Watermill Towd Road, Watermill, NY 11976. www.watermillcenter.org.

RELATED: "ART SEEN: Performance Art Dominates the Watermill Center Benefit" by Pat Rogers. Published July 30, 2013.

________________________________________

Want to know what’s happening in the Hamptons art community? How about the North Fork or NYC? Visit HamptonsArtHub.com to find out.

There’s plenty of art news, art reviews, art fair coverage and artists with a Hamptons / North Fork connection.

Hamptons Art Hub. Art Unrestricted.

________________________________________

© 2013 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. This includes all photographs and images. Text excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to HamptonsArtHub.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.