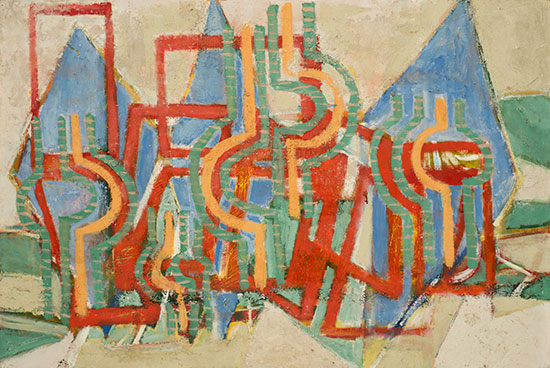

With its current exhibition of works by Ben Wilson, the Quogue Gallery is bringing to light yet another overlooked Abstract Expressionist painter. Wilson’s connections to the Club—as the painters at the core of the movement sometimes identified themselves—are both historic (he worked in the WPA project alongside Rothko and Krasner) and clearly visible in the technical bravura of such paintings as Omar, my pick for the best of the show.

.

"Omar" by Ben Wilson. Oil on composition board, 28.75 x 48 inches. Courtesy of Quogue Gallery.

.

This densely packed work has a bright rhombus at its core, an intense accretion of thick white, silver and grey impasto that builds out from the surface in piled paint mixed with beach sand, taking texture to the point of sculpture. Neither the largest nor the oldest of the works in this important retrospective, it nonetheless commanded the corner of the gallery’s soaring, sunlit rear space with all the swagger commonly attributed to those painters in Wilson’s intimate circle, including Pollock, Kline and De Kooning.

Although Omar was painted in 1986, standing before it I might as well have been at the Galerie Neuf in 1946 when Wilson made his New York debut, attracting the applause of critics and colleagues alike.

An exhibition with this level of historical clout deserves a strong catalogue with biographical and critical texts and a meticulous curriculum vitae, generously provided in this case by Quogue Gallery owners Chester and Christy Murray. An exceptionally valuable separate handout of descriptive captions was written for the show by Wilson’s daughter Joanne Wilson Jaffe, herself an artist with invaluable insight into the technical and intellectual subtleties of these complex paintings. The two publications are essential companions to viewing and fully appreciating the work.

Jaffe’s description of Mozart and Miles, for example, helpfully picks out the key geometric motifs: the three yellow hemispheres that so closely resemble both musical notes and parts of instruments. Jazz and Abstract Expressionism were perfect dance partners in their time, and Wilson clearly knows his music. This painting is a reminder that jazz is not only the epitome of freedom through improvisation but, at its highest level (and Miles Davis would certainly qualify for that superlative), an example of a firm sense of order as well.

Mozart fits with Miles in ways that would be evident to the listener who apprehends the structural soundness of rhythmic and harmonic patterns that hang on for dear life while the winds of improvisation blow through them. Where would that most clearly be in evidence for the connoisseur? Look at a score, the notes and dynamic markings on the page, which are in so many ways the visual basis for this terrific work.

A similar synaesthetic enjoyment of music as scored is offered by Notations, where the stave lines set the horizontal rhythm for a transparent melodic rise and fall of open geometric forms, the phrases in the song floating over the beat.

Both the catalogue and Jaffe’s captions make clear the path from figuration to abstraction that Wilson pursued as he studied in New York and Paris. Born in Philadelphia, the son of Ukrainian immigrants, he grew up in New York. He followed the well-worn path of first-generation Americans to City College, and studied at the National Academy of Design and at City College, but he received the best kind of graduate education with the artists working with the WPA, which he joined in 1935 as part of the mural team.

It was there that he got his technical and graphic chops, and made connections that led to him becoming, only a year later, one of the youngest artists to be included in the stable of the American Contemporary Art (ACA) Gallery in 1936. He maintained his Chelsea studio and painted steadily, not always showing in galleries, until his death in 2001. His papers and sketchbooks along with those of his wife Evelyn, also an artist, are maintained in the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian, an essential resource for scholars.

The paintings of the 1930s were heavy on the haunting imagery also found in those distant gazing figures of Gorky or Rothko in their figural periods. The Holocaust in particular offered Wilson the Dostoevskian source of his most poignant ’30s paintings. A ghost from these works can be found in the face that rises from the depths of Emerging Entity, painted in 1985 but retrieving an unshakable commitment to the emotional basis of his art from 50 years before.

.

"Emerging Entity" and "Omar" by Ben Wilson, oil on masonite. Courtesy of Quogue Gallery.

.

Traces of figuration make the job of viewing Regatta easier. The sail forms and waves whip up a welter of visual motion that perfectly captures the joy of a good race on a day with just the right mix of blue sky and lively breeze.

.

"Regatta" by Ben Wilson. Oil on masonite, 24 x 36 inches. Courtesy of Quogue Gallery.

.

As Jaffe’s annotations make clear, the transition from those heart-rending figural paintings to abstraction was made in the later 1950s, at about the time when Rothko, Newman, Gorky, De Kooning and others were similarly eliminating the realism from their work. The earliest painting in the show, a brooding labyrinth of angled forms, part Kline part David Smith in its construction, is Outrageous Fortune, painted in 1963. The painting hangs somewhat uneasily with its back to the gallery’s window on Quogue Street, in part because if it were in the larger space with the brighter palette of the other paintings it would threaten to suck all the energy out of the room.

.

"Outrageous Fortune" by Ben Wilson. Oil on masonite, 59 x 47 inches. Courtesy of Quogue Gallery.

.

Among the most abstract of the paintings in the show, a small vertical work titled Oracle offers a pensive postscript to that gravitas. This is a desert song of shadows and shrines, with its matte black apertures suggesting the cave in which the enigmatic Delphic pronouncements were made. Art historically, it is closely allied with the tragic works of Motherwell and Gottlieb, with a nod to the charnel houses of Picasso’s grisaille paintings.

.

"Oracle" by Ben Wilson. Oil on masonite, 24 x 18 inches. Courtesy of Quogue Gallery.

.

By 1990, Wilson’s mastery of geometric form was so natural that there is a sense of emptying out the fullness of the gestures and strokes in Bird’s Eye View, which evokes Matisse as well as Picasso in its aerial perspective on forms. Jaffe’s notes wonderfully refer to these forms as “templates” derived from the silhouette of birds. It is certainly one of the most ebullient of the works in the show, with its bright palette of pinks and golds, but it confirms as well the strict Cubist lesson the artist received while studying at the Academie Julien in Paris in 1953-4.

Like a ride in a vintage Boeing Stratocruiser airliner, Bird’s Eye View lifts the viewer to a transcendent height on the wings of a talent honed in the company of those exceptional painters working in what might be called the country’s finest hour in art, the Abstract Expressionists.

.

"Bird's Eye View" by Ben Wilson. Oil on canvas, 34 x 44 inches. Courtesy of Quogue Gallery.

.

_______________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Ben Wilson: An Abstract Expressionist Vision” is on view June 29 to July 19, 2017 at Quogue Gallery, 44 Quogue Street, Quogue, NY 11959. Quoguegallery.com

_______________________________

Copyright 2017 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.