The “Lines of Sight” retrospective of Carmen Herrera on the top floor of the Whitney Museum offers the chance for an exhilarating experience of consummate absorption in pure abstraction. The exhibition boasts numerous strengths, but the peak of the experience, for this reviewer, is to be found in the near-perfect installation of one gallery located at the center of the show. Here the viewer will find what the museum describes as “an unprecedented gathering from what Herrera considers her most important series, Blanco y Verde.”

This “gathering” features nine of the 15 immaculately conceived and executed paintings that Herrera made for this series, dating from 1959 to 1971. This period could easily be considered the apex of Herrera’s career if this rigorous and admirable survey is any indication.

.

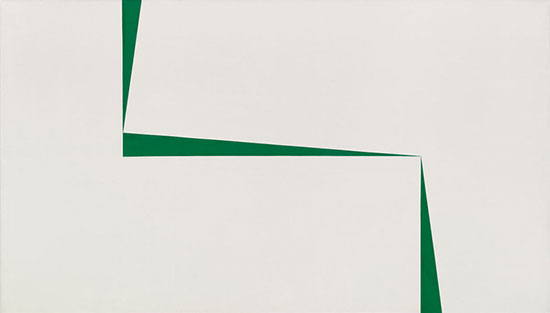

"Blanco y Verde" by Carmen Herrera, 1967. Acrylic on canvas, 40 × 70 inches. Private Collection © Carmen Herrera.

.

Each of the green-and-white paintings in the room has its individual merits, but the massed effect of the nine cleanly demarcated, clear-eyed works, and the generous spacing allotted to the hanging by curator Dana Miller, raise the bar considerably. The effect is close to the level of walking into the small rotunda in Washington’s National Gallery, where Barnett Newman’s Stations of the Cross hang en suite, or the similarly metaphysical immersion in Louise Nevelson’s all-white Chapel of the Good Shepherd, tucked into a corner of the Citicorp building in Manhattan’s midtown.

Herrera and Newman were, incidentally, close friends whose long conversations on abstraction (he had just devised his “zip” mode of composition) and painting were a vital part of her education. With Blanco y Verde, Herrera put white and green in a sensitive scale calibrated to register the slightest weighting of either pan, tipping with each addition of a square inch of either green or white, then re-balanced by the deft addition or subtraction of a square inch elsewhere. The artist likened it to a dichromatic duet between “yes and no.”

My favorite example is the painting made in 1959, in which this balance sharpens the points of a slice of green floating on a snowy white field to such an acute drama that the sliver of bright color has the power to maintain the equilibrium. The balance swings the other way to a green field intersected by white triangles in other works. The 1959 painting is the breakthrough work that the Whitney acquired in 2012, and hung next to an Ellsworth Kelly in the grand re-opening show reviewed here.

.

"Blanco y Verde" by Carmen Herrera, 1959. Acrylic on canvas, two panels: 68 1/8 × 60 1/2 inches overall. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Painting and Sculpture Committee 2014.63 © Carmen Herrera; courtesy Lisson Gallery, London.

.

The Whitney is just one of the many institutions that were late to the party in recognizing Herrera’s talents. A publicity photo of the artist has her smiling like a child in front of a birthday cake as she carefully peels back the masking tape she uses to keep those edges firm. Now that she is 101 years old, the story line on virtually every review is the same: Why did it take the art world so long to catch on to her work?

She was born to an educated family in Havana, and studied architecture there during her first year at university. She arrived in New York in 1939, having married Jesse Loewenthal, who taught English at Stuyvesant High School. The Whitney is proud to note that she was a frequent visitor to its Greenwich Village quarters when she lived on 19th Street and was studying at the Art Students League. She still lives on 19th Street and is in the studio daily.

Loewenthal took a leave of absence and they moved to Paris where, from 1948 to 1953, Herrera discovered her geometric calling and joined the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. Although she and Ellsworth Kelly were in Paris at the same time, the catalogue takes pains to note they remained unaware of each other’s works (despite the kinship of their green-and-white paintings). Among her close friends and colleagues during the Paris years was her fellow Cuban Wilfredo Lam.

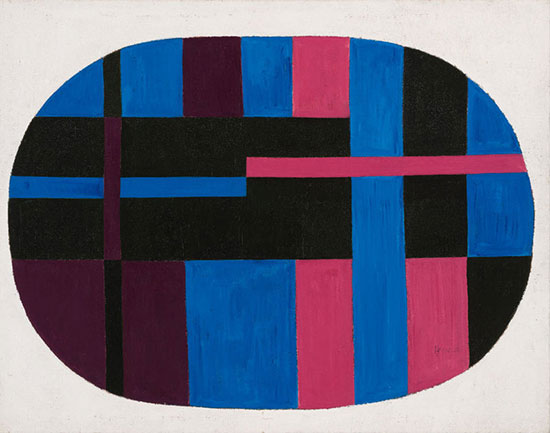

Like a vintage vinyl recording of Maria Callas singing the “Habanera” in her prime, with pops and hisses teasing out the grain of the voice, the Paris paintings, such as A City (1948), have tremendous immediacy. Herrera used paint mixed with sand applied to rough burlap, which provides a texture that the later, more cleanly delineated paintings on primed linen smooth over. Her husband acquired the burlap for stretching in Paris from suppliers to equestrians and farms, because it was used in many cases for liners that kept the saddle from chafing horses’ backs.

The tell-tale difference from the later work is revealed at the edges between colors, which buzz across the woolly fibers of the burlap, blurring the boundaries between blue and gold. The effect is drastically unlike the scalpel-like precision with which she cut the green off from the white in the Blanco y Verde group. Almost like semaphore flags, designed with enough graphic decibels to be read across miles of sea, they assertively pit blue against yellow, red against black for maximum contrast and legibility.

.

"Untitled" by Carmen Herrera, 1948. Acrylic on burlap, 48 × 38 inches. Collection of Yolanda Santos © Carmen Herrera.

.

Drawings are often a path to the personal, even when abstraction at its tightest and most objective seems impersonal. An intimate sense of Herrera’s hand at work in the studio is offered by the limited but valuable selection of her studies, in a shadowy corner near the western end of the building. Trained as an architect, Herrera’s regimentally straight lines assembled three-dimensional ideas for the paintings.

The drawings share the space with four of her estructuras, monochrome sculptures that also tap her inner architect. The correlation of an individual painting and its preparatory study takes a bit of vigorous dedication, and few may make the effort to walk back and forth between the two. But the curious will be rewarded, especially when the “figure” of the triangle wraps around to the edge of the canvas (she used green edges to give a halo on the wall behind certain paintings).

.

Installation view of "Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight" (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 16, 2016—January 2, 2017). Photography by Ronald Amstutz.

.

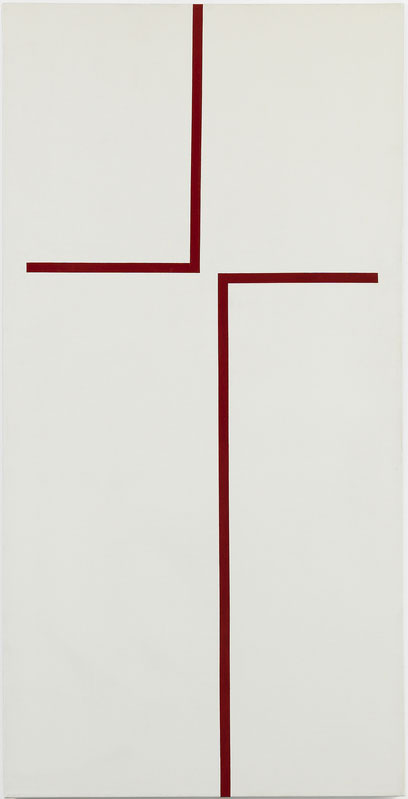

Among the later paintings, the ascetically slender red right angles on a white ground in The Way (1970) holds its own, in my opinion, with the brilliant green-and-white paintings at the core of the show.

.

"The Way" by Carmen Herrera, 1970. Acrylic on canvas, 60 × 30 inches. Private collection © Carmen Herrera; courtesy Lisson Gallery.

.

Circulating through the three sections of the exhibition, dutifully checking back in on the works on paper and approaching the low-key sculpture installation from every angle, I kept coming back to that central, splendid room of green-and-white paintings. Like the quasi-mystical effect of the Agnes Martin exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum uptown, my appreciation for the sheer elegance of the work had become an infatuation.

I was reminded of verses by the poet and art collector Wallace Stevens, who had a thing for Cuba as well as Cezanne and his greens. The “Blanco y Verde” series reminded me of a joyful stanza from “Credences of Summer,” Stevens’s ode to the utopia of aesthetic surrender and the way that beauty of this sort is a refuge:

It is the natural tower of all the world,

The point of survey, green’s green apogee,

But a tower more precious than the view beyond,

A point of survey squatting like a throne,

Axis of everything, green’s apogee…

______________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight” is on view September 16, 2016 through January 2, 2017 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York, NY 10014. www.whitney.org

______________________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.