Her commanding art disrupts and deforms space. Since the 1980s Doris Salcedo has created art to pay witness to brutalities plaguing her native Colombia. Over 50 years of civil strife have traumatized that country, a sad record for countries in the Western hemisphere.

"I believe war is the main event of our time," Salcedo has said. "The epic, mechanized scale of death that has characterized the 20th and 21st centuries has become systematically produced and thoroughly inscribed into our everyday lives."

Working with this grimly vast subject matter, her art—on view through July 17, 2016, in "Doris Salcedo" at Pérez Art Museum Miami—conveys both individual and collective loss.

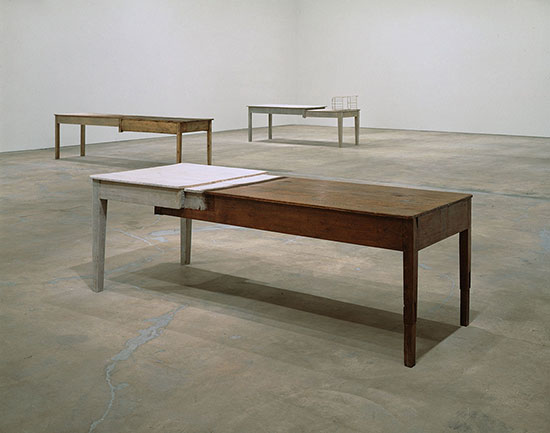

The artist creates painstaking modifications of humble objects like beds, chairs, doors and tables, some of which were collected from victims and families the artist encountered during her research. One example would be the gently fused tables of Unland: the orphan's tunic. Two tables are intricately textured with silk, human hair, and thread.

.

"Unland: the orphan’s tunic" by Doris Salcedo, 1997. Wooden tables, silk, human hair and thread, 31 1/2 x 96 1/2 x 38 1/2 inches. “la Caixa” Contemporary Art Collection Installation view, SITE Santa Fe, 1998–99 Photo: Herbert Lotz.

.

Many more examples can now be seen in the Pérez Art Museum Miami exhibition, billed as the largest presentation of her art to date, with some 40 works produced during 30 years. Over the course of her career, Salcedo has tirelessly given unique shape to the legacy of violence.

"The experiences I attempt to address are not anecdotes. My work is about the memory of experience, which is always vanishing, not about experiences taken from life," she explained when she received the Hiroshima Art Prize for Peace in 2014.

Since the early 1990s, Salcedo has been hailed as a major sculptor of her generation. "She is considered one of the most highly renowned and respected artists of Latin America," Latin American art scholar and Florida International University professor Carol Damian said in an interview about the PAMM exhibition. "For me she even transcends Latin America because the issues she addresses resonate with so many people throughout this very violent world we live in."

Though "Doris Salcedo" was organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, where it was first exhibited, Damian said, "I think it puts PAMM on the map for doing something this sophisticated and global. Of course it's always better to organize something, but at least [PAMM] took advantage of its availability because you know it had to cost a lot of money. She was there for a month installing and she made them transform all those spaces. She is beyond perfectionist, very obsessive-compulsive about almost everything she does."

Salcedo lives and works in Bogatá, where she was born. In 1980 she received a BFA at Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano, focusing on painting and theater. There she studied with painter Beatriz González, considered one of the first Colombian painters to find inspiration in mass media.

Soon afterwards, Salcedo earned an MA in 1984 at New York University, where she was influenced by the work of Joseph Beuys and his ideas about "social sculpture." This activist, conceptual background is embedded in her art and may explain why it contains no specific images of refugees or people kidnapped, tortured, or murdered.

In this "face-less" way, her work stands in contrast to some of Latin America's best known politically conscious art. Consider the photographs, films and community projects of Chilean-born Alfredo Jaar, who has made art concerning military conflicts, famine and genocide. From a slightly earlier generation, there are the paintings and sculpture of Oswaldo Guayasamín (1919-1999) of Ecuador. His figurative style urgently captures the struggles of impoverished indigenous people in Ecuador and beyond.

Hours of Intense Field Work

At the basis of Salcedo's sculpture, installations, and large-scale site-specific works are hours of intense field work, interviewing individuals who have experienced tragedy and loss, who forever grieve the abrupt "disappearance" of family members and loved ones now presumed dead.

There was the massacre of banana plantation workers snatched from their homes in 1988 that provoked her sculptures in the late 1980s and 1990. A few years later she interviewed rural Colombian women who had been forced to leave their homes to find safe haven from another deadly round of conflict. Mass graves scarring the countryside of Colombia as well as gang violence in Los Angeles have led to more field work, more quietly searing art.

An especially striking aspect of the current PAMM exhibit is the myriad ways Salcedo exploits the simple act of stitching thread through cloth. In her art, sewing, a form of so-called "woman's work," becomes a rich metaphor for the process of mourning, given the inventive materials she employs to recall the simple act of sewing, as if preparing a shroud. She sometimes calls these stitches "sutures," recalling a doctor's practice of stitching together, or suturing, lacerations to repair wounds.

Time-honored rituals of mourning, such as marking a loss with flowers or candles, are central to her art. The fascinating documentary on her career, running continuously at the museum and showing her large-scale site-specific installations created around the world, makes the artist’s focus on these rituals abundantly clear.

"Our very humanity resides within the devotion or contempt that we assign to our practices, processes, and rituals of mourning," Salcedo has written. "An aesthetic view of death reveals an ethical view of life, and it is for this reason that there is nothing more human than mourning."

Her signature stitches or sutures are particularly evident in the spectral Atrabiliarios, occupying the silent whiteness of a single gallery. Your attention is completely focused on the 43 niches carved into gallery walls, each containing women's shoes, sometimes one by itself and sometimes in pairs. They are arranged in small groupings, as if representing women casually standing in a room, but of course only the indistinct memory of these unknown souls is suggested.

.

"Atrabiliarios" (detail) by Doris Salcedo, 1992–2004. Shoes, drywall, paint, wood, animal fiber and surgical thread, 43 inches and 40 boxes, overall dimensions variable. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Accessions Committee Fund purchase: gift of Carla Emil and Rich Silverstein, Patricia and Raoul Kennedy, Elaine McKeon, Lisa and John Miller, Chara Schreyer and Gordon Freund, and Robin Wright.

.

Each niche is covered with a swath of partially opaque animal fiber eerily resembling skin. It's held in place by stitched and knotted black threads, like those intended to close wounds. The cloudily transparent "skin" evokes scars that cannot vanish.

Quietly extraordinary is A Flor de Piel, composed of hundreds of red rose petals treated and surgically stitched together. It's arranged loosely on the floor like a wrinkled bedsheet or shroud that has not yet been wrapped around a body. Looking closely at the petals one can see thousands of tiny veins, giving them the look of skin, underscoring their delicate vulnerability.

.

"A Flor de Piel" by Doris Salcedo, 2014. Rose petals and thread, 525 x 256 inches. Installation view, Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2016. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: World Red Eye.

.

According to notes provided by Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, A Flor de Piel refers to a Spanish idiom translated as the English expression for wearing one's heart on one's sleeve. It arises from the artist's research into the life of a Colombian nurse who was kidnapped and tortured to death. Salcedo has said it "started with the simple intention of making a flower offering to a victim of torture, in an attempt to perform the funerary rite that was denied her."

More stitching is evident in the clothing incorporated into her sculptures, from the tufted embroidery in a wedding dress to stacks of ironed cotton shirts.

In her Untitled of 1998, a tall wooden cabinet is filled with grayish-white concrete, making it impossible to see through its paneled double doors. Perhaps this cabinet once held dishes. Perhaps it was a wardrobe for dresses. A few wrinkled traces of clothing can be seen emerging from the concrete blocking the doors. These traces are also saturated with concrete. As subtle memories of absent bodies, they are persistently, harrowingly visible.

.

"Untitled" by Doris Salcedo, 1998. Wooden cabinet, concrete, steel, glass and clothing 721⁄4 x 39 x 13 inches. Collection of Lisa and John Miller, fractional and promised gift to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Photo: David Heald.

.

"Untitled" (detail) by Doris Salcedo, 1998. Wooden cabinet, concrete, steel, glass and clothing 721⁄4 x 39 x 13 inches. Collection of Lisa and John Miller, fractional and promised gift to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Photo: David Heald.

.

In this context, thin blades of grass punctuating her Plegaria Muda evoke the persistent act of stitching--and even, to some extent, mourning. Multiple wooden tables, about the size of coffins, are set up in a maze-like pattern. In each case, an inverted table rests on top of a wooden table, with what resembles a thick layer of earth between. This layer is planted with seeds of grass. Grass pushes up through tiny holes in the inverted table.

.

"Plegaria Muda (detail)" by Doris Salcedo, 2008 -10. Wood, concrete, earth, and grass, One hundred and sixty-six parts, each: 64-5/8 x 84- 1/2 x 24 inches, Overall dimensions variable. Installation view, Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2016. Inhotim Collection, Brazil. Photo: World Red Eye.

.

"Plegaria Muda (detail)" by Doris Salcedo, 2008 -10. Wood, concrete, earth, and grass, One hundred and sixty-six parts, each: 64-5/8 x 84- 1/2 x 24 inches, Overall dimensions variable. Installation view, Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2016. Inhotim Collection, Brazil. Photo: Jason Mandella. Reproduced courtesy of White Cube.

.

This work's title is loosely translated as "silent prayer." There's an incantatory sense of repetition about its formal structure. The viewer can almost hear prayers for the disappeared being whispered over and over. All the while new life moves forward.

The image of grass pushing up through so many coffin-like tables recalls resonant lines from Carl Sandburg's famous 1918 poem, "Grass," about battlefields later covered with grass. "I am the grass,” the poet wrote, “I cover all."

_______________________

BASIC FACTS: "Doris Salcedo" is on view through July 17, 2016, at Pérez Art Museum Miami, 1103 Biscayne Blvd., Miami FL 33132. www.pamm.org.

_______________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.