Turn a modernist architectural masterpiece over to a comprehensive survey of a 20th century master and the result is the monumental “Moholy-Nagy: Future Present” exhibition on view through September 7, 2016 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

The ideal presentation of this Laszlo Moholy-Nagy retrospective along the spiral of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim is a triumph of sensitive installation. There is a clear link between the choices made by the museum’s senior exhibition designer, Kelly Cullinan, and the artist’s own idea of a “spatial kaleidoscope,” as articulated in theoretical texts on the experience of space.

.

"Moholy-Nagy: Future Present," Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, May 27 - September 7, 2017. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

.

Backward glances across the rotunda at a Guggenheim retrospective have the virtue of conflating the differences made by decades, allowing an intense appreciation of an artist’s progress. This is especially revealing in the case of a thinker as attuned to the shifting relations of past, present and future as Moholy-Nagy.

The show marches chronologically up the famous winding ramp from the earliest paintings and drawings (a grim but strangely lyrical crayon drawing of barbed wire dating to 1918) to the latest, most expressive and gestural paintings made in 1946, the year he succumbed to leukemia at age 51. The only exception to the chronological rule is a side gallery on the first level devoted to the slick Room of the Present (Raum der Gegenwart), an installation that Moholy-Nagy conceived in 1930 but never saw in his lifetime.

.

"Room of the Present (Raum der Gegenwart)" by László Moholy-Nagy, constructed in 2009 from plans and other documentation dated 1930. Mixed media, 442 x 586.8 x 842.8 cm. Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven. © 2016 Hattula Moholy- Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

.

This installation elegantly if austerely constructs a room-sized maze of flickering films, photographic reproductions framed in chrome, replicas of architecture, theater sets and, timed to revolve on a turntable for a few minutes at irregular intervals, his kinetic Light Prop for an Electric Stage (Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne, 1930). Bathed in a cinematic blue light, the highly polished, angular steel construction inside its case within the room is not much larger than a professional kitchen appliance, and looks something like a Marcel Duchamp collage come to life. As a sleek antechamber to the progress of what follows, the Room of the Present sets the utopian tone perfectly.

.

"Room of the Present (Raum der Gegenwart)" by László Moholy-Nagy, constructed in 2009 from plans and other documentation dated 1930. Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven. Foreground: Light Prop for an Electric Stage (Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne), 1930. Exhibition replica, constructed in 2006, through the courtesy of Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Hildegard von Gontard Bequest Fund © 2016 Hattula Moholy- Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

.

Like Kandinsky, Moholy-Nagy was a lawyer who fled the constraints of a profession he disliked and a government in Austria-Hungary that could not abide intellectuals to pursue his vocation in Germany (Kandinsky went to Bavaria, Moholy to Berlin).

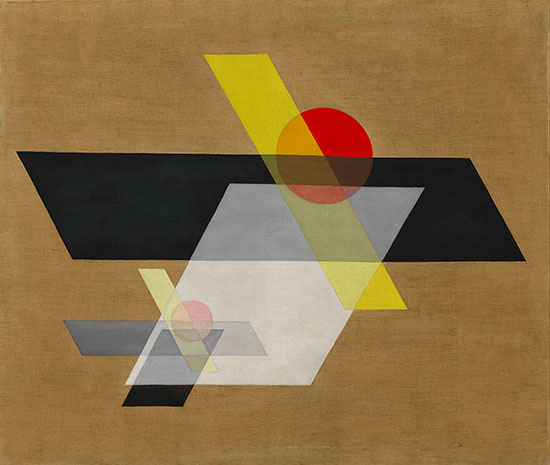

The Radio and Railway Landscape of 1919-1920 is one of several absorbing early works, crisply painted on burlap in bold colors and clear-eyed geometric tribute to the industrial marvels of Berlin. His blues, reds and yellows are mixed, artistic tones, not the straight graphic primaries of a scientific approach, and his touch is poetic rather than rigid no matter how many cleanly defined straight edges were guided by the ruler (the clean lip of paint indicates the tools used). The tensile strength of the tape-like red lines, crossed before the defined forms in Yellow Circle and Black Square (1921), elevates geometry to physics and experiments in force.

.

"A 19" by László Moholy-Nagy, 1927. Oil and graphite on canvas, 80 x 95.5 cm. Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor, MI. © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

Whether oil on canvas or on panel, the delicate pencil under-drawing and the paler tones ensure an intimacy, as in the refined greys of LIS (1922), one of my favorite paintings in the show. This window into the process via the hand and its marks is most transparent in the many drawings and collages included, which suggest a labor-intensive studio ticking along with a metronome’s precision.

Remembered as one of the heroic exiles who brought the Bauhaus to the United States,, Moholy-Nagy was born in 1895 in Austria-Hungary (as the southern part of Hungary was then known) and moved to Berlin following a brief stay in Vienna, where he first encountered the Constructivists as well as Dada. The industrial vocabulary of many of his early paintings (gears, cogwheels, electric power pylons) is attributable to his stay in Berlin, where even before the Bauhaus years he was tightening the edges of his still life paintings to an architectural finish.

Under the impersonal spell of geometric abstraction, it can be easy for a viewer to forget the significance of his cultural identity. To address that issue, some tutoring was provided at the press preview by Katya Valevich, an international freelance curator and critic who shuttles between Moscow and Manhattan. In front of the artist’s paintings of the 1920s, she pointed out the correlations between Moholy-Nagy and the Constructivists, as well as the way the works in the show responded to the ebb and flow of Soviet optimism in the early 1920s under Lenin (whose death in 1924 is reflected, she suggested, in the shadow play of the works afterward).

.

"A II (Construction A II)" by László Moholy-Nagy, 1924. Oil and graphite on canvas, 115.8 × 136.5 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection 43.900. © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

Even after his German and American residencies, the Slavic side of Moholy-Nagy (like the Hungarian side of Liszt or the Polish melancholy of Chopin in music) set him slightly apart from such Bauhaus figures as Josef Albers or Johannes Itten.

At the time of the opening of the Moholy-Nagy show, I happened to have been reading Julian Barnes’s latest novel, The Noise of Time, about the dreadful price Dmitri Shostakovich’s art paid to politics. Early in the novel, the composer recalls the sort of utopian vision of the era when Lenin was on the ascendant: “In that optimistic time—really so very few years ago—when the future of the whole country, if not of humanity itself, was being remade, it had seemed as if all the arts might finally come together in one glorious joint project.”

Unlike the composer Shostakovich, who denounced Stravinsky and became a puppet of dictators including Stalin, Moholy-Nagy made his move to central Europe, joining the Bauhaus in Weimar and moving with it to Dessau. He was a key figure in the integration of arts education through interdisciplinary work in design as well as painting, branching into photography and photograms, book and stage design, and typography.

In 1934 he moved his family to Holland, then on to London and eventually, in 1937, to Chicago, where he became founding director of the New Bauhaus (now the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology). He never returned to Europe.

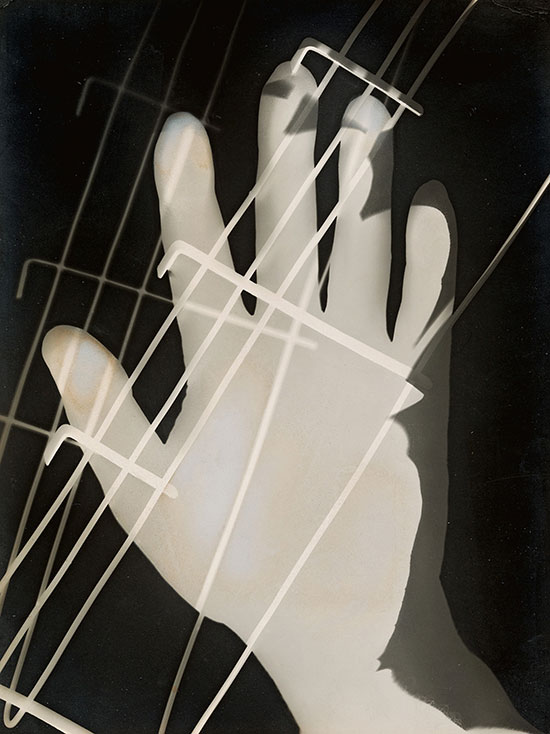

As a teacher, professional designer and experimenter, Moholy moved through many media, inventing the camera-less “photogram,” photomontages and Schwitters-like collages in which the Dada influence is pronounced. The most lyrical of these is Leda, a photomontage assembled and altered by pencil in 1925 that takes its place in the canon of paintings and literature on the myth from Leonardo through Cy Twombly.

The exhibition showcases a panoply of metal constructions, many of the photograms, book covers, enamel paintings and drawings. It should be on the “to see” list of graphic designers, especially if they are still somehow working in the quaint medium involving ink and paper.

.

"Photogram" by László Moholy-Nagy, 1926. Gelatin silver photogram, 23.8 x 17.8 inches. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Ralph M. Parsons Fund. © 2016 Hattula Moholy- Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: © 2015 Museum Associates/LACMA.

.

Moholy-Nagy thrived in the United States. The crystalline geometries of the paintings he made in Chicago (designated by the CH in their titles) ring in true harmonies of form and color, as in the clean lines and high-contrast play of figure and ground in CH 14 B (1938). Generally I dislike multi-media ventures into plexiglass and other industrial materials, but the shadow play that doubled the floating shards in CPL 4 (1941) is vastly more engaging than any gimmick.

It turns out that Moholy-Nagy was a major player not just in the founding of the American Bauhaus but in the start of the Guggenheim itself. This was back when it was the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, as pulled together by the curator Hilla Rebay; she presented a solo show of Moholy-Nagy’s work shortly after his death.

Walter Gropius wrote of the artist: “I remember his peculiar freshness when he was facing a new problem in his art. With the attitude of an unprejudiced, happy child at play, he surprised one by the directness of his intuitive approach. Here was the source of his priceless quality as an educator: his never-ceasing power to stimulate and to carry away the other person with his own enthusiasm.”

.

"CH BEATA I" by László Moholy-Nagy, 1939. Oil and graphite on canvas, 118.9 x 119.8 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection 48.1128. © 2016 Hattula Moholy- Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

___________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Moholy-Nagy: Future Present” is on view May 27 to September 7, 2016 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1071 5th Avenue, New York, NY 10128. www.Guggenheim.org.

___________________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.