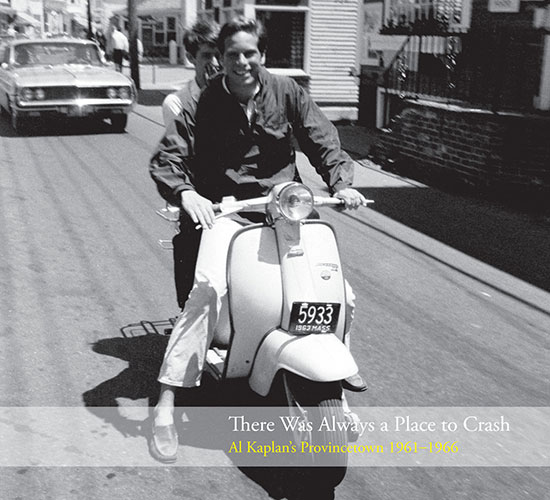

A photographer on the cusp of a career spends five summers in a village on the cusp of change. Both are outliers: Al Kaplan and Provincetown, Massachusetts.

That's the backstory to the book "There Was Always a Place to Crash: Al Kaplan's Provincetown 1961-1966," edited by Brett Sokol. It brings fresh insight to a storied place in American culture and history.

With its quaint New England clapboard houses and spectacular setting on Cape Cod's outermost point, Provincetown has long nurtured outliers, nonconformists and creative spirits.

.

Cover of "There Was Always a Place to Crash: Al Kaplan's Provincetown 1961-1966."

.

American artist Charles Webster Hawthorne founded this country's first outdoor school of figure painting, Cape Cod School of Art, in Provincetown in 1899. Among the artists he went on to teach was Norman Rockwell. July 1915 saw the founding of the Provincetown Players theatrical group, which quickly made a mark by presenting the work of contemporary American playwrights. The company attracted the likes of Eugene O'Neill, John Reed, Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and Susan Glaspell.

In the early 20th century, artists and writers summered in Provincetown, working during the day and gathering at night to talk about art around bonfires on the beach. Much later, Hans Hoffmann and Norman Mailer were drawn by its windswept allure and Kaplan himself arrived to shoot some of those bonfires.

By the 1970s, Provincetown was widely-recognized for its gay population, leading to its current status as an LGBTQ tourist destination.

Thoroughly Displeasing Vibe

Still, there were times when the town didn't always embrace adventurous outliers, and that's when Kaplan showed up with his camera. As the 1960s began, young sandal-clad drifters, musicians and artists, with their messy hair and libertine lifestyle, were joining forces with resident gays and lesbians to create a vibe thoroughly displeasing to Provincetown movers and shakers.

Steve Desroches, writing in 2015 for Provincetown Magazine when Al Kaplan's Provincetown photographs were exhibited at Gallery Ehva there, noted two newspaper articles encapsulating the historic change transforming "P-town," as it's sometimes called.

First, there was "Provincetown Beatniks: Unloved and Unwashed," appearing in 1962 in Cape Cod Standard-Times. Four years later, The New York Times published "New Pilgrims in Provincetown: Cape Cod Village Is The Site of A 'Beatnik' Beachhead that Is Angering Local Residents." This article reported how those adventurous outliers Kaplan loved to photograph in the summer were raising eyebrows (to say the least) of folks who considered the town their primary residence.

When The Times got to this story, Kaplan had been covering it for five summers. As his son Jonathan recalled to journalist Brett Sokol, who wrote the introduction to the book, Kaplan used to say about that period: "We weren't beatniks, that was my father's generation."

In the fall of 1966, Kaplan left for Miami to begin his photojournalism career in earnest.

"I had seen a couple of Kaplan's photographs from this period, the early 1960s, up in Provincetown,” journalist Brett Sokol said in a phone interview after the book was published by Miami's Letter16 Press. “He was really an accomplished Miami photographer who had been here in Miami until his passing in 2009. I think that early stuff just got pushed to the wayside. He moved on."

.

Atlantic House, July 1966, photo by Al Kaplan.

.

Rescuing Analog Photography In Digital Age

Curiosity whetted, Sokol and the book's designer, Francesco Casale, got access to Kaplan's archive from the photographer's family. As co-founders of the non-profit Letter16 Press, they spent hours sorting through negatives to choose the selection appearing in this book.

"One of the ironies of the so-called digital revolution," explained Sokol, "is that while it's certainly made photography much easier to access and share these days, it's made it that much harder to work with analog photography. The costs of doing transfers from analog to the digital realm have skyrocketed. The labs that handle it are disappearing every day. You can't do this and make a profit."

Without financial assistance from the Knight Foundation, the book probably would never have seen the light of day. Knight contributed a grant of $20,000, which covered roughly half of the total budget, Sokol said.

Kaplan's book from Letter16 Press is the first in a planned series of hardcover books designed to rescue from obscurity little-known analog photography in Miami.

These Provincetown photographs offer a fascinating slice of history. "It's an incredibly seminal period, not just in the history of Provincetown, which is America's oldest continuous art colony and one of its earliest gay communities, but it's also a really important period in the counterculture of America," Sokol said. "It's one of those places that gets talked about in the same way as Haight Ashbury in 1960s San Francisco."

But there has been no real photographic record of that time in Provincetown, he added, until this book.

A Camera 'Loaded and Ready to Go'

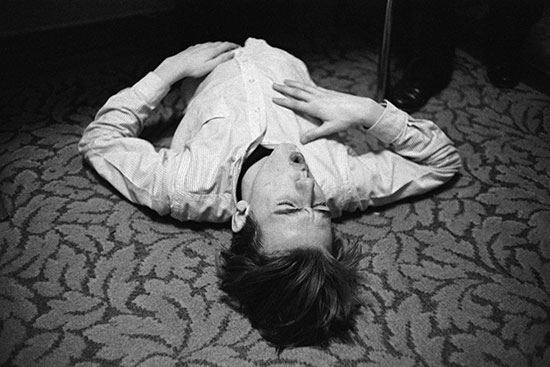

Kaplan began spending summers in Provincetown when he was 18, having fallen in love with his ever present 35mm camera, shooting roll after roll. He affectionately shot his high school buddy Rene Ricard lolling on the floor. Ricard was soon bound for Manhattan to become a film star for Andy Warhol and later a seminal art critic.

.

Rene Ricard, January 1963. Photo by Al Kaplan.

.

Kaplan "wasn't just some photographer parachuting into the scene. He was part of it," said Sokol. "This was his world. These were his friends, his lovers, his scene."

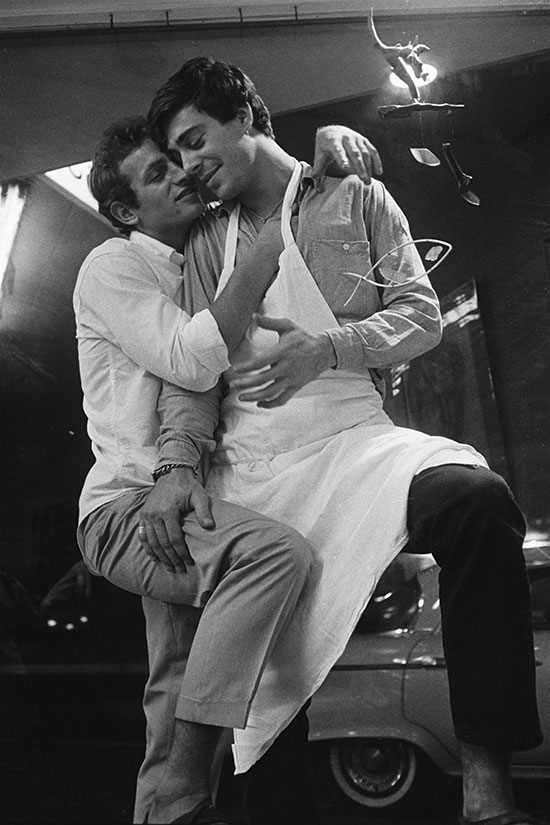

There's a raffish intimacy to these photos transcending the more formal documentary work of journalism. They are composed with a sharp, empathetic eye. So there are affecting scenes that another photographer, not so well known to his subjects, could have missed, especially at a time when smoking pot or embracing a same-sex lover could lead to arrest or worse. Throughout are captions from Kaplan's journals.

Take the scenes of two men, dancing late one night in a coffee shop. Kaplan writes, "Suddenly this couple noticed my camera and started camping it up, playing to the camera, and I fired off a few frames … It was just so damned spontaneous! So full of love! I'm glad I had the camera loaded and ready to go."

.

Commercial St., August 1962. Photo by Al Kaplan.

.

Other shots show people sleeping on scruffy mattresses in the rickety treehouse owned by Prescott Townsend, legendary Boston Brahmin and a gay activist before there was such a term. Is that red wine, vomit, or blood staining the sheets? Certain photos bring to mind more questions than they answer about what this rebellious era really was like. Just what happened when sign-waving demonstrators, a counter-demonstrator, and police encountered each other at the Hiroshima Day Memorial Walk in August 1963?

.

Josephine Del Deo at Hiroshima Day Memorial Walk, August 1963. Photo by Al Kaplan.

.

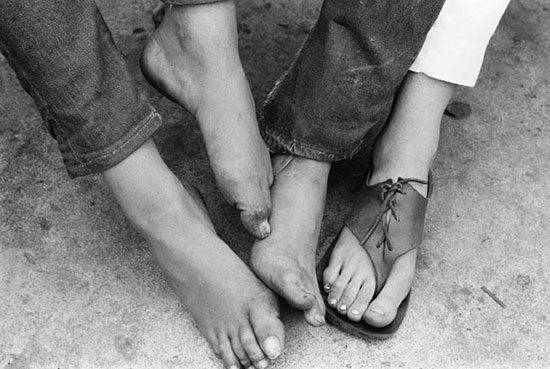

And then there are gracefully structured moments, bringing the viewer into a long ago time and place: The sandal-maker in his shop surrounded by tools of his trade. The curious quartet of four dirty Beatnik feet, only one wearing a sandal. A cluster of people unloading a van or setting up camp on Race Point Beach, photographed to suggest a loosely choreographed modern dance that's about to begin, with Provincetown's treasured dunes as backdrop.

.

Unknown sandal-maker, photo by Al Kaplan.

.

Mystery feet and unknown toes, Provincetown, August 1962. Photo by Al Kaplan.

.

Having shot Townsend wearing shorts and a beret in a book-lined room, Kaplan wrote in his journal years later, in a prescient reflection on that time early in his career:

"Prescott summered at his house in Provincetown and wintered in his house in Boston. Both places were always full of people straight and gay, young and old, and of every race. There were artists and writers and musicians. There was always a place to crash and something to eat."

.

Prescott Townsend, July 1963, photo by Al Kaplan.

.

___________________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.