A Degas show is a sure hit for New York’s Museum of Modern Art, even when the dates on the pieces are very early and the works on view are monotypes.

“Edgar Degas: A Strange New Beauty” is the first solo show at MoMA for French artist Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas at MoMA, a studious gathering of 120 monotypes and 60 related works reflecting this medium’s influence on his paintings and pastels. While Degas (1834-1917) is historically considered more of a “foundational figure” than a Modern, the premise of this show is that Degas is at his most Modern in the monotypes.

.

Installation view of "Edgar Degas: A Strange New Beauty" at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (March 22-July 24, 2016). Photo by Martin Seck. © 2015 The Museum of Modern Art, New York

.

Indistinct, marvelously enigmatic blobs of pooled ink and paint, blurred draftsmanship that obscures faces, and hazy horizons align with the endgame of MoMA’s traditional agenda, as outlined by curator Alfred Barr in 1938 in a famous diagram tracking the progression in modern art toward abstraction.

By far the most eccentric moment in the show is the galumphing green blob that the rolling monotype press herded from the left edge of the sheet into the middle of Forest in the Mountains (1890), turning an accidental ink spill into an unforgettable moment of early Abstract Expressionism. It can be read as a hedgerow or copse, or enjoyed as a precursor to Robert Motherwell’s oval processions.

.

"Forest in the Mountains (Forêt dans la montagne)" by Edgar Degas, 1890. Monotype in oil on paper. Plate: 11 13/16 x 15 3/4 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Louise Reinhardt Smith Bequest.

.

Proceeding chronologically from his first attempts at the medium in the 1870s through a phenomenal group of landscapes made in the 1890s, the show chronicles a three-decade romance between Degas and a marvelously sensitive medium that combines the spontaneity of drawing with the technological subtlety of the printmaking studio. Effectively a drawing or painting made on a metal plate then directly printed on a sheet of paper, the monotype—as the “mono” prefix suggests—is supposed to make a single impression.

Degas scoffed at this rule, pulling as many as four works from one plate, using the leftover ink or paint to produce a “degraded” or ghost image that he enhanced with pastel. Sometimes he added paint or ink before pulling the second and third state. Half the pleasure of the MoMA show is calibrating the metamorphoses of ballerinas or rural hillsides from one state to another.

Also, ever mindful that the surface of the copper or zinc plate is plate is slick and the ink or paint is viscous, Degas would soak the paper (as he often did for pastels) so the fibers would absorb the color more fully. Through this technique, the potential for color escaping control—spilling and bleeding into unforeseen shapes—becomes part of the story.

There are two types of monotype featured in the MoMA show. In “dark field,” a curtain of black ink is spread on the plate to start, and the image emerges as the artist scratches into it. In “light field,” color is added to a plate that prints on white. The “Strange New Beauty” exhibition proceeds from the “dark field” pieces, his earliest attempts, to larger scale works in which high tones and opaque, bright areas of color come closest to Impressionism. The first room reflects his experiments with the medium under the influence of his friend Ludovic Lepic, up to his elbows in black ink, immersed in the sheer compulsive joy of a new toy.

“He is no longer a man, he is a plate,” the studio hands joked. Degas has gone through the press, emerging with an efficient new language in which to translate his beloved café singers, prostitutes and dancers emerging from the gloom into the novel brightness of electric light. A scintillating example of the “dark field” is Three Dancers (1878-80), a horizontal piece that conveys the movement that meant so much to Degas at the ballet, as well as some of the shock of bright theater lights on pale shoulders and faces.

.

"Three Ballet Dancers (Trois danseuses)" by Edgar Degas, c. 1878-80. Monotype on cream laid paper. Plate: 7 13/16 × 16 3/8 inches. Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts.

.

An ancillary theme of the exhibition is the poignant effort Degas made to keep up with the rapid pace of Paris in his time. Passersby are represented striding past him so brusquely on the sidewalk of the Champs-Élysées (his eyesight was weak even when he was young) that their faces are indistinct. The ink is swiped across the delicately drawn features on the plate just as memories grow indistinct the moment a conversation retreats.

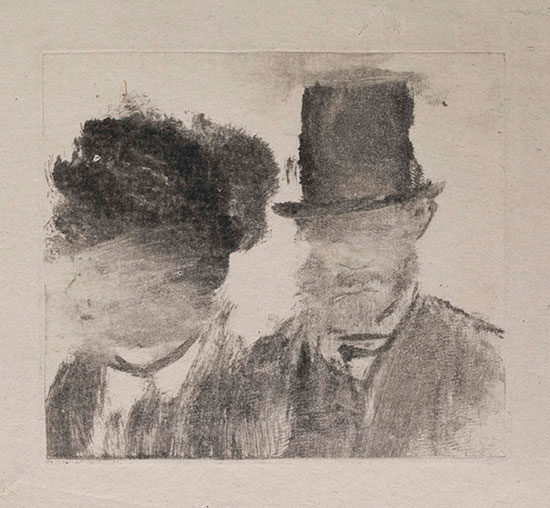

Both Heads of a Man and a Woman and On the Street, from the late 1870s, convey the illusion of bodies in continual motion, part of the Heraclitean flux of urban life in an age of accelerated change. The expressive gestures, loose and atmospheric in many cases, imbue the works with a kinetic energy that is almost cinematic (in 1893, the cinema was invented).

.

"Heads of a Man and a Woman (Homme et femme, en buste)" by Edgar Degas, c. 1877-80. Monotype on paper. Plate: 2 13/16 x 3 3/16 inches. British Museum, London. Bequeathed by Campbell Dodgson.

.

"On the Street (Dans la rue)" by Edgar Degas, c. 1876-77. Monotype on China paper. Plate: 6 3/8 x 4 13/16 inches. Mrs. Martin Atlas.

.

Degas was fascinated by time-motion photographic studies and the idea of capturing the dancers’ movement, or the look of the landscape as he sped through it on a train, tram or horse-drawn carriage. All these are part of the vocabulary of the show. In the gloom of The Fireside, marked by his thumbprints and fingernails in ways that anticipate the monotypes of Jasper Johns, the flicker of shadows cast by the glowing hearth is palpable. Picasso was among the first serious collectors of monotypes by Degas, especially these darker scenes from brothel and interior.

.

!["The Fireside (Le Foyer [La Cheminée])" by Edgar Degas, c. 1880-85. "The Fireside (Le Foyer [La Cheminée])" by Edgar Degas, c. 1880-85. Monotype on paper. Plate: 16 3/4 x 23 1/16 inches, sheet: 19 3/4 x 25 1/2 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, and C. Douglas Dillon Gift, 1968.](https://hamptonsarthub.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Degas-the-fireside.jpg)

"The Fireside (Le Foyer [La Cheminée])" by Edgar Degas, c. 1880-85. Monotype on paper. Plate: 16 3/4 x 23 1/16 inches, sheet: 19 3/4 x 25 1/2 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, and C. Douglas Dillon Gift, 1968.

.

The show moves into the bright light of day with the later series of landscapes. In September 1890, Degas and the sculptor Paul-Albert Bartholome set off on a journey in a two-wheeled horse-drawn carriage. Their route took them from Paris southeast along the Seine toward Fontainebleau and eventually to the chateau of a friend in the village of Dienay, in Burgundy. Degas used his razor-sharp memory to make an astonishing group of monotypes that I found to be the highlight of the exhibition, in part because he made a major change in materials, method and process.

Although the monotypes made in the 1870s and 1880s used printer’s ink, as was customary in the medium, when Degas returned to the process in 1890, he used oil paint. Viewers familiar with the artist’s work will likely be intrigued by the match between the paints used in his paintings of the period and those applied to the monotypes. Some of the conservation issues posed by mixing media were tricky, as when he used pastel to add to an oil paint or ink image. Thankfully he did this after they were dry, but not always with ideal results when it came to the adherence of the pastel.

The epitome of these cheerful antidotes to the earlier, threatening black works is the incandescent Landscape with Rocks (1892), flecked with glowing granules of turquoise and tangerine.

.

"Landscape with Rocks (Paysage avec rochers)" by Edgar Degas, 1892. Pastel over monotype in oil on wove paper. Sheet: 10 1/8 × 13 9/16 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Purchase with High Museum of Art Enhancement Fund.

.

A major challenge for Jodi Hauptman, MoMA’s senior curator of drawings and prints, was re-uniting “cognate pairs” pulled from the same plate, including the linked images of the village of L’Esterel in autumn (Autumn Landscape, L’Esterel, two versions). The paler, second version has the faded, ghostly look while the robust hill forms and fall colors have the power of patinated bronze in the first pull.

.

"Autumn Landscape (L’Estérel)," by Edgar Degas, 1890. Monotype in oil on paper. Plate: 11 7/8 x 15 3/4 inches, sheet: 12 1/2 x 16 1/4 inches. Private collection.

.

"Autumn Landscape (L’Estérel)," by Edgar Degas, 1890. Monotype in oil on paper. Plate: 11 7/8 x 15 3/4 inches, sheet: 12 1/2 x 16 1/4 inches. Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California. Museum Purchase, B. Gerald Cantor Fund.

.

The monotype, incidentally, is alive and well in contemporary art. Such hotshots as Wayne Thiebaud, Elizabeth Peyton, Carroll Dunham, Chris Ofili, Peter Doig and Mel Bochner are routinely invited into print studios to try their hand.

I have always been partial to the delicate veils of grey in the work of Nancy Haynes, who mastered the medium in the 1980s during an extended period of printmaking. I also admire the long-term commitment to the medium of Myrna Burks, who has a studio in Orient on Long Island’s North Fork, and Michael Mazur.

In the spirit of Degas and the “strange beauty” he pulled from his plates (the phrase was applied to his work by the poet Stéphane Mallarmé), these contemporary artists are continuing a legacy that is tapped into one of the most exciting chapters in the history of Modern art.

__________________________________

BASIC FACTS: "Degas: A Strange New Beauty" is exhibited March 26 to July 24, 2016 at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street, New York, NY 10019. www.moma.org.

__________________________________

Copyright 2016 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.