Jane Wilson and Jane Freilicher were splendidly endowed painters who were the same age, shared a studio, partied heartily on Flying Point Road in Water Mill, and dazzled the New York and East End art scene. The heartfelt bonhomie of “Jane Freilicher and Jane Wilson: Seen and Unseen,” like the pulsing colors of their paintings, resounds like laughter through the galleries of the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill.

.

Installation view of the exhibition, "Jane Freilicher and Jane Wilson: Seen and Unseen." Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York. October 25, 2015 through January 18, 2016. Photo: Gary Mamay.

.

The backstory is so rich that it risks overshadowing the art. Freilicher was born in Brooklyn (as was Lee Krasner, her neighbor) and studied studio art at Brooklyn College. She was one of the lucky protégés of the great German Abstract Expressionist Hans Hofmann, both in Provincetown and in New York, before taking a master’s at Teachers College of Columbia University. Wilson grew up on an Iowa farm (colossal skies dominate her landscapes) and took her MFA at the University of Iowa, where her teacher was Philip Guston. The two Janes met in 1949 in New York and shared a studio in a large bedroom of a rented house on Flying Point Road in Water Mill starting in 1957.

.

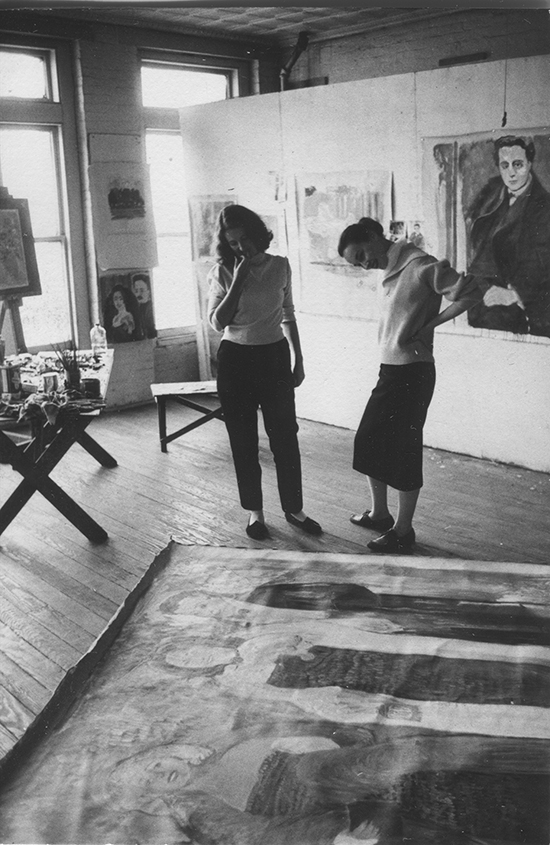

Jan Freilicher and Jane Wilson, Water Mill, New York, 1962. Photograph by John Jonas Gruen.

.

In the elegantly designed catalogue for the exhibition, Alicia Longwell—Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Chief Curator, Art and Education at the Parrish and author of one of the four substantive essays—quotes Freilicher on the support they offered one another: “There was some sort of affinity in our painting, but it wasn’t actually that we influenced each other. Maybe a certain reinforcement.”

.

Jane Wilson and Jane Freilicher at Jane Freilicher’s studio in Hoboken, New Jersey. Painting, by Jane Freilicher, is titled "Opening Night."

.

Another terrific essay in the catalogue is offered by Deborah Rothschild, connoisseur of intimate circles whose brilliant scholarship on the art and lives of Gerald and Sara Murphy is justifiably renowned. During the panel discussion at the show’s opening, Rothschild cannily revisited a photo shoot for a lifestyle magazine in September 1957, when Wilson and Freilicher were 32.

The “day in the life” piece, in a monthly called Coronet, showcased the two Janes on a Hoboken ferry, perusing a profile of Hofmann in an issue of Life magazine that mentioned Freilicher and glamorously dancing the tango. “They all looked like they were having so much fun and everybody was there,” said Rothschild, echoing a famous line about the Murphys' glamorous hospitality during the Jazz Age. One of the scrapbook photos that makes the catalogue such fun features not just the two Janes but Robert Rauschenberg, Larry Rivers and clan, Grace Hartigan, Jasper Johns, Roland Pease and others cavorting on the beach in Water Mill in 1959.

.

Water Mill Beach, 1959. Front Row: Robert Rauschenberg, Steven Rivers (standing), Larry Rivers, Herbert Machiz, Grace Hartigan (lying down), John Myers. Back row: Maxine Groffsky, Joe Hazan, Mary Abbott, Jasper Johns, Sondra Lee, Jane Freilicher, Roland Pease, and Tibor de Nagy. Photograph by John Jonas Gruen.

.

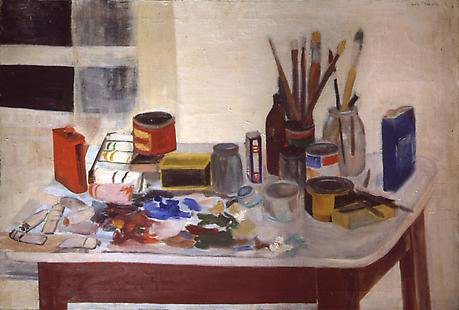

The siren call of two terrific painters—one a fashion model and the other no plain Jane—both clearly possessed of a talent for the art of living as well as laying down gorgeous colors with solid studio technique, should be enough. But wait, there’s more! John Ashbery, who lived in the same building as Freilicher and was an indefatigable champion of their work in print, is an inextricable part of the narrative. Ashbery wrote an essential critical essay on Freilicher, published in 1986, that includes a brilliant reading of The Painting Table (1954), a still life he owned and used for a cover image of a collection of art essays which is one of the touchstones of the Parrish show.

.

"The Painting Table" by Jane Freilicher, 1954. 26 x 40 inches. Courtesy nybooks.com.

.

The title of the piece refers to a metal table in the kitchen of Freilicher's East Village apartment that she used as a palette (the taches of paint are in the central foreground) with jars and coffee cans holding about nine brushes and tubes of paint in some disorder. The painting shuttles between realism and abstraction in a diplomatic way that resonated for Ashbery, whose relaxed poetics of inclusion shares many of the same qualities.

Ashbery wrote: “The result is a little anthology of ways of seeing, feeling and painting, with no suggestion that any one way is better than another. What is better than anything is the renewed realization that all kinds of things can and must exist side by side at any given moment, and that that is what life and creating are all about.”

.

Installation view of the exhibition, "Jane Freilicher and Jane Wilson: Seen and Unseen." Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York. October 25, 2015 through January 18, 2016. Photo: Gary Mamay.

.

That perception is the perfect clue to the surprisingly dissimilar works of the two painters: abstraction and realism, lyricism and analytic study, color and its subdual are all in play. There are symphonies in white by Wilson, notably White Still Life II (a Gorky cascade bleached of its greens and reds), Bay House (1964) and the utterly atmospheric Rain on Avenue B (1965), which are not just Whistlerian in their harmonies but suggest what Emily Dickinson might have done had she left Amherst for the Art Students League crica 1950.

.

"Bay House" by Jane Wilson, 1964. Oil on canvas, 40 x 60 inches. Private Collection, Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York. Photograph by Steven Bates.

.

The suggestions of trees or rooflines in these paintings is as aphoristic as a Dickinson fragment, while the winged touch of a white brush stroke evoking the surface of Peconic Bay are the artistic answer to the poet’s famed -em dashes, elliptical launching pads into unspoken infinities. As Mimi Thomson, who wrote the catalogue essay on Wilson, pointed out during the panel discussion on October 24, “She wanted to find substance in things that didn’t have substance.” Dickinson’s phrase for the same evocative power was “the gorgeous nothings.”

The heavier, browner palette is found in Wilson’s Hammer and Tongs (1972) with its meticulously worked drapery study, and the architectural complexity of the workbench in Stretcher Pliers (1972), which is a damn sight more complicated painting than it seems at first because it balances several planes from foreground to middle ground to a second stage of the middle ground on a tilting shelf surface.

The answer to Ashbery’s favorite still life by Freilicher is Wilson’s Four Paper Palettes (1973), with some of the same vocabulary of cans and brushes and studio implements in a convergence of compositional strategies that might encourage some to think these two are Picasso and Braque.

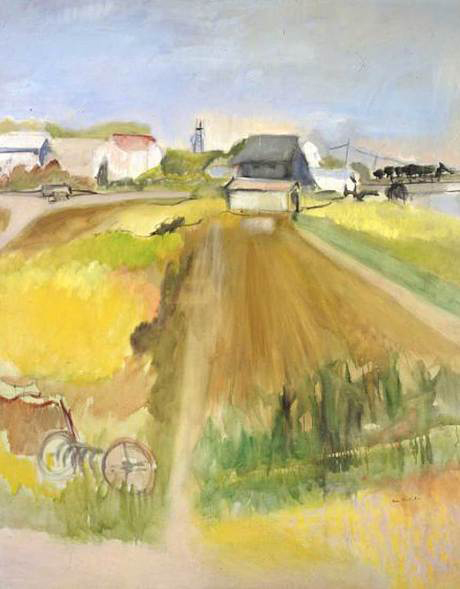

The landscapes breathe fresh air into the exhibition, glowing with the Pierre Bonnard palette that is cited by many art historians in discussing the two artists’ work, thanks to a 1948 show that influenced Freilicher especially. Her imposing vertical Farm Scene (1963), uses a high horizon of huddled barns and a white house as a point of convergence from which a torrent of color, greens through rusts and peach, flows downward to a foggy bottom at our feet, along which a hedgerow and hay rake interpose a flimsy barricade. Its flimsiness is betrayed by one furrow piercing this horizontal element to offer a path into the meadow.

.

"Farm Scene" by Jane Freilicher, 1963. Courtesy of telegraph.co.uk.

.

Freilicher’s entirely different style is found in The Mallow Gatherers (1958), which hangs right beside Farm Scene in the show and uses a similar composition (a tightly clustered group of buildings gathered high on the vertical form). In this work, the stand of pulsing Malva, a type of hibiscus whose fruit has medicinal properties, is painted in a way reminiscent of Joan Mitchell’s Giverny gardens. The rock at the lower right has volume and some of the silhouette of a Guston boulder (although Guston was the teacher of Wilson), while Hoffman’s influence is felt in the rectangular black lines meeting and crossing in the buildings above as well as in the rapid oscillation of the brush in the magenta patches she uses as a chromatic sharp note.

.

"Untitled Abstraction" by Jane Freilicher, 1960. Oil on canvas, 49 x 60 inches. Courtesy of Tibor De Nagy Gallery.

.

Freilicher at her most abstract is a delight in many of the ways that Helen Frankenthaler can please, as in Blue and Green Abstraction (1960) with its bands of thinned oil, or the wispy, floating forms of Henry Ford’s Dunes (1961), the lightest touch in the show. With the exhibition opening just as the corner turns on autumn, this gem by a painter of bright energy and panache brought to mind Ashbery’s poem “Never to Get it Really Right” (1987):

“I never do know how to end any season,

Do you? And it never matters; between the catch

And the fall, a new series has been propounded

With brio and elan.”

________________________

BASIC FACTS: "Jane Freilicher and Jane Wilson: Seen and Unseen" remains on view through January 18, 2016.

The Parrish Art Museum is located at 279 Montauk Highway, Water Mill, NY 11976. 631-283-2118; www.Parrishart.org.

________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.