“If you've got the garden, I've got my whole life.”

—Jarod Kintz

The landscape schemes by Edmund Hollander Design grace the pages of scores of high-end home and architectural magazines, indicating that this is one of the most sought after landscape design firms working today. Edmund Hollander and Maryanne Connelly are the firm’s principals, and a new volume of their East Coast estate gardens by the ever reliable Monacelli Press is assured to land on coffee tables everywhere, full of ideas for expanding one’s foliage.

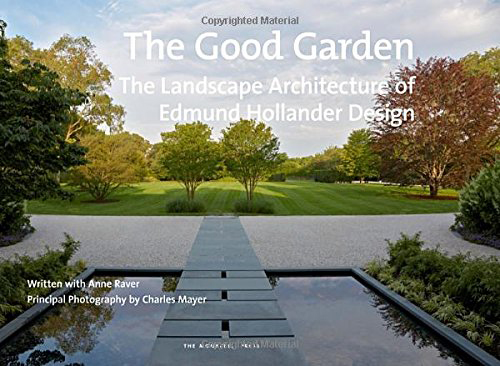

“The Good Garden: The Landscape Architecture of Edmund Hollander Design” by Anne Raver Monacelli Press, New York, 2015) includes more than 300 color illustrations among its 320 pages, a perfect balance as gardens don’t produce words, just images. With that in mind, still it’s a picture book page-turner, back and forth, comparing this estate verdure with the ascending layers of flora on this one. Many will head off to Edmund Hollander Design looking to add the specialness missing from their land, and again as many will be nursery-hopping with their purse in one hand and this book in the other.

“The Good Garden: The Landscape Architecture of Edmund Hollander Design” by Edmund Hollander and Anne Raver. Published by The Monacelli Press.

The design firm has a curious regional flavor—most of the designs were executed within a 200-mile radius of Long Island—giving the two principals a special familiarity with the stone, woods, and botany of this area. The stirring effect of their design was manifest at a book party held recently in the stunning gardens of Cheryl and Michael Minikes in East Hampton. In contrast to the hated giantess houses suddenly belching out of modest lots, the Minikes’ house crouches low to the ground and is surrounded by acres of stunning plantings created by Edmund Hollander Design.

The designs of this firm are unassailable and the book is seamless. Still, perhaps because the designs are so resplendent, while browsing this volume, one cannot help but compare these installations to some of the great gardens of Europe, particularly those at Versailles and of that ilk. These parks and gardens were theater, along with the ornate architecture, that was intended to keep the royalty’s subjects in line by indicating their obvious inferiority to this center of power. (Of course, history tells us that a contrary opinion took hold in October of 1789.)

Hollander Design’s gardens are human scale and intimate, there is no dramaturgy of power here. Instead there is a warming of the spirit with the infinite varieties of petal and pistil, the magnificence of what the Germans call geist and the hope of perpetual beginnings.

In this critic’s opinion (with the full disclosure that much of my work is sculpture), what is missing from these gardens is statuary, the kinds of centerpieces that are prominent in the gardens of Versailles or the Mirabell Gardens of Salzburg, among others. Granted, garden siting is a peripheral area of contemporary sculpture, and most offerings today vacillate between zombie formalism and concrete versions of Pan with his flute. Furthermore, I have noted recently that there are fewer bronzes or marble carvings in gardens around London; instead there are embellishments of stunning topiary, as if Edward Scissorhands lived nearby.

Still, to my point, in the gardens of Versailles, architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart arranged classical sculpture of the civilizations of antiquity among the plantings. This has the effect of bringing the depth of age to the newness of a perennial growth. For a regional example, an uneven but sometimes good grouping of contemporary sculpture is found on the grounds of the LongHouse Reserve in East Hampton. It might prove salutary for Hollander Design to familiarize themselves with current sculpture trends, so as to vary their less-is-more Mies van der Rohe dictum of Modernist reduction.

One standout chapter reflecting this Modernist simplicity is entitled Dunefields. Here the designers reveal their vision by sculpting the sand dunes with nearly invisible plantings of beach plum and bayberry. This work exhibits their talent as great landscape architects; indeed the sculpture mandate of feeling and form based on idea is beautifully reflected in these magnificent arrangements of biology. Here we see living sculptures of raw nature that never tire and spring anew after the white winters. It represents everything positive in life.

In the book, Hollander discusses his “three ecologies.” First is the found environment; secondly the way the client pictures the property; and thirdly the related as-built elements. While this seems to parallel conceptually the themes of “The Three Ecologies,” a 2000 book by the late philosopher Pierre-Félix Guattari (1930-1992), Hollander maintains there is no connection.

But no bother: I wouldn’t have trusted Guattari to grow crabgrass and I doubt that philosophy is Hollander’s principal interest.

The text is written by Anne Raver. Given her love of words and plants, this essay nicely complements these hundreds of pages of exquisite gardens.

_________________________

To see photos by Charles Mayer for "The Good Garden: The Landscape Architecture of Edmund Hollander Design," view our slideshow:

View Slideshow_________________________

Copyright 2015 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.

poor felix that was a good line