The artist Keith Sonnier has effected something of an illumination in Southampton, transforming Tripoli Gallery into a glowing phoenix that merges industry, illusion and the ephemeral in the exhibition “Keith Sonnier: Elliptical Transmission” on view through August 17, 2014.

Since the 1960s, the central element in Sonnier’s art has been light. His neon sculpture, often architectural in scale, has been exhibited worldwide and his seminal works in incandescent light, translucent fabric and minimal geometric form helped reinvent the sculptural idiom.

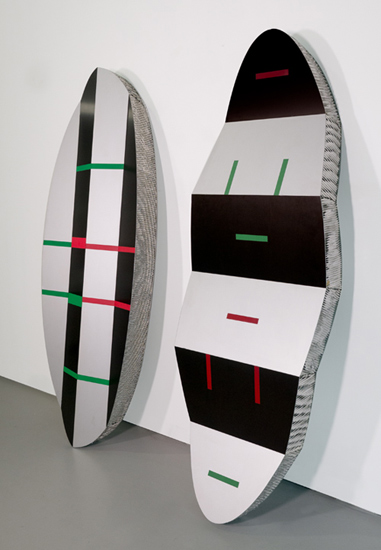

An inveterate experimenter, Sonnier has employed materials as diverse as satellite transmitters, satin, flocking and bamboo. But it is his work in neon, allowing him to draw with light and color in space, that is the sine qua non of his oeuvre. At Tripoli Gallery, the works on view range from Gran Twister, 2012, a majestic conflagration of loops that hover above the exhibition space as if in orbit, to Space Slipper, 1992, a diptych of fragmented ellipses that lean against the wall like errant surfboards. In the latter, Sonnier fractures the planar surface, a thematic confab that fuses two- and three-dimensional form.

.

"Gran Twister" by Keith Sonnier, 2012. Welded steel, neon, argon, transformer, aluminum excel, reflectors and hardware, 44 x 82 x 22 inches. © Keith Sonnier/Artist Rights Society. Photograph by Genevieve Hanson, courtesy Pace Gallery.

.

"Space Slipper" by Keith Sonnier, 1992. Corrugated aluminum, paint, 38 x 79 x 29 1/2 inches (two elements). © Keith Sonnier/Artist Rights Society. Photograph by Caterina Verde, Courtesy Pace Gallery.

.

A transplant from Louisiana’s gulf coast, Sonnier emerged in New York’s heady art world in the 1960s among a generation of artists poised for revolution. The ’60s, a decade of radical change in America, devolved from its beginnings and the national idealism of the Kennedy era into a sort of cultural madness that, by the end of the decade, saw three heartbreaking political assassinations, massive student unrest, a bevy of seemingly intractable social problems and the Vietnam War.

Reflecting this turbulence and tumult, the art world moved from the cusp of minimalism to an atmosphere redolent of rebellion. Through process, installation, performance and conceptual art, this generation of artists subverted convention in all its forms, reinventing the art world with works that were transitory, dematerialized and wholly unorthodox. The results were electric, resulting in an exhilarating blurring of the lines between painting and sculpture, inside and outside, and present and future tense.

Sonnier went to graduate school at Rutgers University, a stone’s throw from New York. It was a hotbed of teaching artists and thinkers from the Fluxus movement (Alison Knowles, Allan Kaprow and George Brecht) and Pop Art (Roy Lichtenstein and George Segal). And while neither movement held much immediate interest for Sonnier, their confluence provided a sizzling aesthetic fuel for him.

As the art object was being transformed into something active, site-specific and often impermanent, Sonnier’s focus was expansive, addressing process and temporality. He laid pieces on the floor, leaned them against walls, and created conceptual volumes with string, rope and rubber. By the time he discovered neon, he was well on his way to the history books, exhibiting with the legendary gallerist Leo Castelli as early as 1969.

In Dining Chandelier, Sonnier dips into his past and the 1950s light fixtures that dotted his Evangeline Parish home in Louisiana. Mounted on the wall, neon tubes swirl in a gentle fracas of soft yellow, white and grey/blue, coiled and whirling like scribbles in thin air.

In fact, it is memory that drives much of Sonnier’s art. Growing up in Cajun country in the small town of Grand Mamou, his early life was one in which the segregated South worked to ensure that his extended French Cajun family remained on the margins of a broader cultural milieu. Yet within those margins Sonnier found an endless stream of soulful source material ranging from his mother’s Louis XV bedroom set to the local cinema owned by his aunt, who screened French film classics night and day for the French speaking locals who made up 80 percent of the population.

Drawing on unconscious sensations from childhood, travel, and other places and things, Sonnier’s art resonates with a quality that is almost acoustic; not because of the low hum of electrical transformers, but because his art possesses a musicality that helps to tease out the sensuality, theatricality and corporeality of memory.

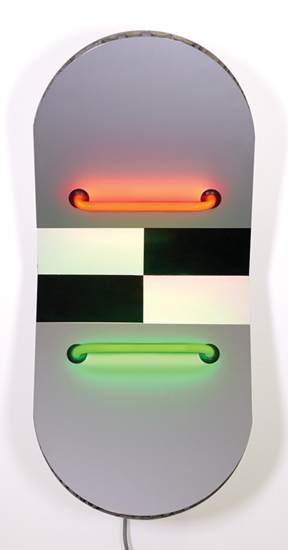

In the Bodo Junction series, Sonnier was pressed to recall where his title for the works came from—somewhere deep in the recesses of his mind. Then he remembered: it was from George Cukor’s film “Bhowani Junction,” starring Ava Gardner and Stewart Granger, a film that he had watched some 20 or 30 times as a teenager. The sculptures, which look like shields or types of armor, recall earlier works in which the artist employed a geometric alphabet of glass shapes intermingled with linear neon elements.

.

"Bodo Junction I" by Keith Sonnier, 2005. Neon, paint, aluminum, 29 x 13 x 10 inches. © Keith Sonnier/Artist Rights Society. Photograph by Caterina Verde, Courtesy Pace Gallery

.

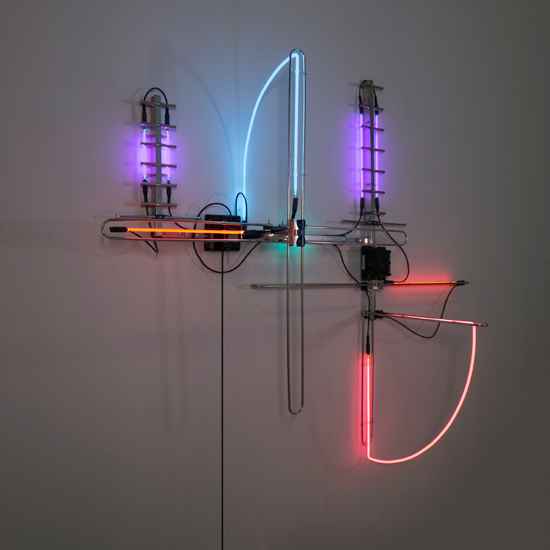

Even so, the concept of nostalgia in his art is an internal property, one that would not be discernible if not for evocative titles that hint at an oblique narrative. In Propeller Spinner (Antenna Series), 1990, the artist took inspiration from the ubiquitous television and radio antennas, now obsolete, that were a part of nearly every home in America.

.

"Propeller Spinner (Antenna Series)" by Keith Sonnier, 1992.

Aluminum and neon, 75 x 79 x 29 1/2 inches. © Keith Sonnier/Artist Rights Society. Photograph by Caterina Verde, Courtesy Pace Gallery.

.

Sensuous and complex, the luminous sculpture appears as if it might take flight. But it’s not because it has propellers or spinning parts; nor does it look at all capable of flight. It is in the magical collision of technology, calligraphy and poetry that Keith Sonnier’s work radiates the experience of the body, the eccentricity of the Southern Gothic tradition and the patois of his origins.

The works in this show are sexy incantations in which a language of curves, paddles, loops and hardware coalesce with a ferocious and unmitigated grace.

BASIC FACTS: “Keith Sonnier: Elliptical Transmission” remains on view through August 17, 2014 at Tripoli Gallery of Contemporary Art, 30 Jobs Lane, Southampton, NY 11968. www.tripoligallery.com.

_________________________________________

Copyright 2014 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.