While “What Is a Photograph?” at New York’s International Center of Photography may not deliver 100 percent on the thesis to which its title lays claim, it does effectively differentiate aspects of photography-as-a-studio-practice from its other forms, such as photojournalism.

By contrast with ICP’s ground floor exhibit of the great Robert Capa’s works in color, produced in the last decade of his brief life, the concurrent “What Is a Photograph?” is a veritable Mardi Gras of improvisation. Located in the downstairs galleries, the 21 artists selected by ICP curator Carol Squiers don’t so much answer the question; they examine the expansiveness and materiality of the photograph and its many constituent parts. Juxtaposed next to Capa’s searing camera lens, the results are bracing, and both exhibits go a long way toward defining and redefining the concept of the photographic eye.

Imagine the world before photography – a time before the relentless documentation of our lives, our wars and our city streets of the modern age. Many tried, but it would be the artist Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre who was first to succeed in capturing an image through the use of light and chemistry. The 1839 debut of the daguerreotype, as it became known, would signal a cultural revolution that offered a new form of realism so magical that it was met with apprehension, if not downright foreboding.

The daguerreotype was a one-of-a-kind print created without the use of a negative. The process employed a precise and elaborate collision of silver, sodium, iodine and gold chloride on copper plate: in essence the Polaroid of its day. And perhaps not surprisingly, Daguerre was not a chemist but a painter of some note, living and working in Paris and this, I think, is key to the thesis of “What Is a Photograph?.” Let’s face it: give a studio artist some light absorbing paper, a darkroom and a bucket of photo emulsion, and all bets are off.

And so it feels like a free-for-all as viewers descend into the exhibit, a riot of color, electricity, abstraction and new media. Most of the works are wedged so tightly into the lower galleries that it feels a little like a crowded subway platform. But never mind—the cheek by jowl installation lends a kind of velocity to the exhibit, as if the last four decades of photographic experimentation were all happening right before your eyes.

Mariah Robertson’s 154 hurdles toward the entrance like a Chinese dragon, its playful loops tempered by a sense of ceremonial drapery. Robertson employs old school darkroom techniques (such as those used to make photograms) as she rakes over a 100-foot length of photographic paper, morphing it into a ribbon of color and form like a Slip n’ Slide that has crossed over to the Cedar Tavern.

.

"154" by Mariah Robertson. ©International Center of Photography, 2014. Photograph by John Berens.

.

"154" by Mariah Robertson. ©International Center of Photography, 2014. Photograph by John Berens.

.

On an opposite wall, Jon Rafman marries the elegance of the Greek bust with computer algorithms, producing a hybrid of 3-D form that bursts into surrealistic abstraction. At the end of the hall Marlo Pascual skewers the portrait of a young beauty with fluorescent tubing while Liz Deschenes’s homage to the zoetrope grips the wall in a vertical sequence of inky black pools.

.

Artwork by Jon Rafman. ©International Center of Photography, 2014. Photograph by John Berens.

.

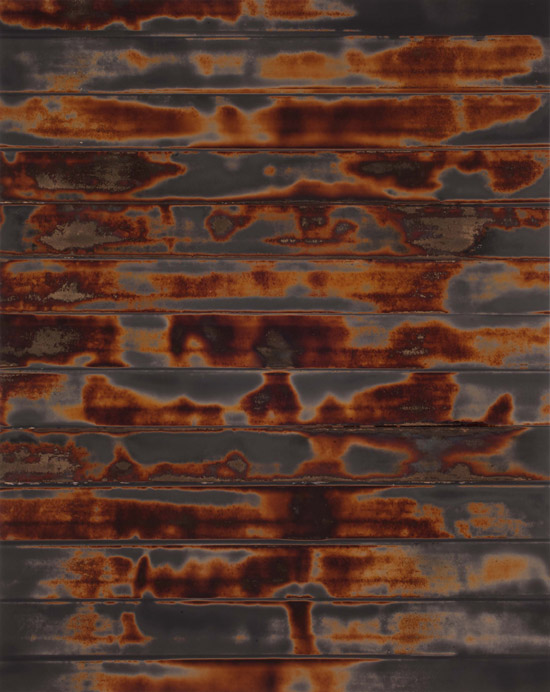

Around the corner, Sigmar Polke, Lucas Samaras and Gerhard Richter—the old lions—hold court with insurgent works that run roughshod over such artistic orthodoxies as the viability of the picture plane or the integrity of the negative. They squeeze, squish and mutilate surfaces and subjects, wrenching new bodies of work from whole other bodies of work. Samaras’s gooey manipulations of Polaroid film yield an intoxicating parade of non-sequiturs and Richter’s slathers of sticky paint squeegeed over snapshots and family photos possess the kind of chewy veracity you can feel between your teeth. Marco Breuer’s physical interventions in the photographic process yield a sumptuous, gritty depth that melds like chocolate in the belly of Abstract Expressionism.

.

"Untitled (Mariette Althaus)" by Sigmar Polke, Early 1970s. © 2013 Estate of Sigmar Polke/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn; Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

.

"Photo-Transformation" by Lucas Samaras, June 2, 1976. © Lucas Samaras, courtesy Pace Gallery; Photo: Kerry Ryan McFate.

.

"16.3.03" by Gerhard Richter, 2003. © Gerhard Richter, courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

.

"Study for (Metal/Day)" by Marco Bruer, 2000. © Marco Breuer, courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

.

Onward into the future, Owen Kydd’s “durational photographs” explore the near stillness of simple objects that come alive through subtle shifts of light and reflection. Kydd’s moving images—color saturated videos, in fact—are meditations on cinéma vérité, and their stealthiness and luscious sense of solitude is enchanting. Moving glacially, the works chart a course that comes nearest to the photographic objectivity that was an early standard of the medium. Similarly, Letha Wilson slices into the American West with incisive geographic cutaways that reveal our nation’s majestic physical history while eclipsing it at the same time.

.

"Pico Boulevard (Nocturne)" by Owen Kydd, 2012. Courtesy the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery. © Owen Kydd.

.

"Colorado Purple" by Letha Wilson, 2012. Concrete, chromogenic print transfer, and wood frame. Courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures, New York. © Letha Wilson, courtesy Higher Pictures, New York.

.

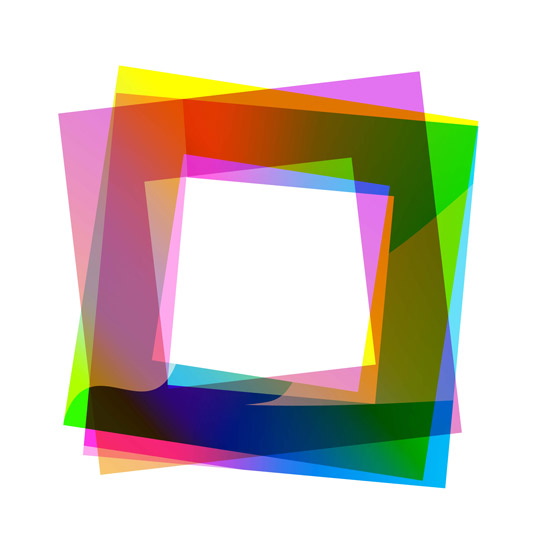

David Benjamin Sherry, Matthew Brandt and Christopher Williams create variants in landscape photography that are morphed by time, process and intellectual certitude. Inventive (and cameraless) photograms by Floris Neusüss and Adam Fuss are diverting if a little flatfooted here; and as for that pesky digital revolution, only a handful of artists here work with digital technology. Among them, Artie Vierkant’s cross-platform works stand out. Stunningly modern, Vierkant pollinates visual media like a colony of honey bees, swapping originals with copies, interchanging physical and digital imagery and commingling the material world with software technology and the internet. For Vierkant, the computer monitor is the new white cube.

.

"Nachtbild (48)" by Floris Neusüss , 1991. © Floris Neusüss. Coutesy the artist and Von Lintel Gallery, New York.

.

"Image Object Friday 7 June 2013 4:33PM" by Artie Vierkant, 2013. © Artie Vierkant, courtesy Higher Pictures, New York.

.

But most poignantly, Alison Rossiter’s sheets of expired photographic paper yield a swell of haunting, tactile images printed, in some cases, on paper dating back to 1900. She began collecting expired sheet film in 2007—the titles here indicate film expiration dates—and her prints from that film effect a collaboration with the past that is truly soulful. Part lamentation and part a celebration of the silvery, baroque chemistry that brought photography into the world, Rossiter’s poetic images possesses the lucidity of Julia Cameron and the stunning simplicity of Daguerre.

.

"Kilborn Acme Kruxo" by Alison Rossiter, exact expiration date unknown, ca. 1940s, processed in 2013 (#1). © Alison Rossiter, courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

.

While not exactly revelatory, “What Is a Photograph?” is a provocative sampler of artists engaged in the medium at its most vigorous levels of experimentation.

BASIC FACTS: “What Is a Photograph?” is presented from Jan. 31 to May 4 at the International Center of Photography, 1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street, New York, NY 10036. www.icp.org.