“Charlotte Park: The 1950s”

Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center

I was privileged to know Charlotte Park from my early childhood. Park and her husband James Brooks became my mentors when I decided to become an artist in the early ’70s. Later, in1989, Park asked me to come help inventory their works, and it was then I came to understand just how powerful an artist she was.

At that time, I was already a great admirer of her work from the ’70s and ’80s, which I was most familiar with growing up. To me that period of her work was on the same level as Agnes Martin; the elements of painting were reduced down to a few essentials so that the artist could convey the most delicate of feelings in the most economical way possible. There is something tender, and even palpable about the decisions one sees in Park’s paintings from this period.

When I discovered her earlier work from the ’50s, it astounded me. I was amazed by the gutsiness of these paintings, which are the subject of the current exhibition, “Charlotte Park: The 1950s”, at the Pollock-Krasner House in Springs, NY. For starters, they stood up to anything I had seen made by either men or women working in the '50s.

.

"Gysophilia" by Charlotte Park, 1970s. Acrylic on canvas. Estate of the Artist. Courtesy Spanierman Modern, NY.

.

Like all the exhibitions at the Pollock-Krasner House, the paintings in this show are arranged around the living room and sitting room on the first floor. Because of the intimate and personal setting, viewing art there is always a special experience. In the case of Park's work, it's even more so as one can imagine—given the period of the works shown and Park's close ties to Pollock and Krasner—that indeed these paintings could have easily hung in this setting in the 1950s. The organization and installation of the show, curated by Pollock-Krasner House Director Helen Harrison, is superb and brings out all the strengths this body of work has to offer.

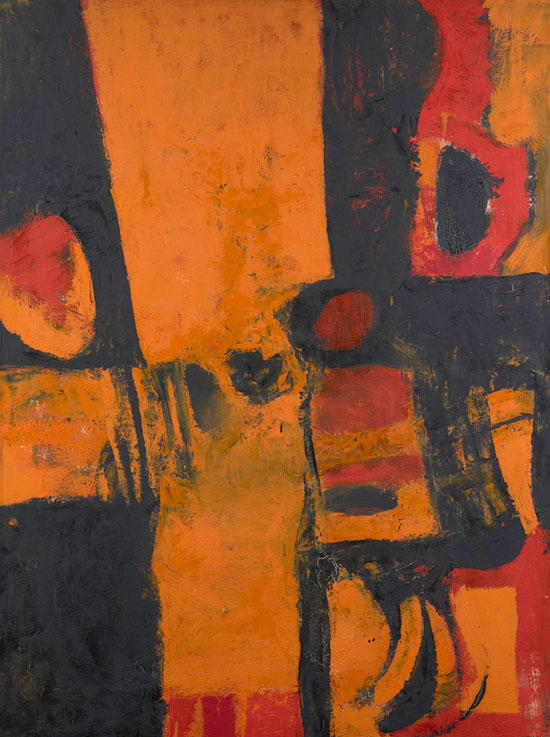

The strong tones of orange, red and black, as seen in Aztec, c. 1955, Initiation, c. 1955, Parade, c. 1955 and Lament, c. 1955 -- all included in this show -- were inspired, Park told me, by such Goya works as 3rd of May and what are known as the "Black Paintings."

.

"Aztec" by Charlotte Park, 1955. Oil on canvas, 22 x 13 inches. Estate of the artist, Courtesy Spanierman Modern, NY.

"Initiation" by Charlotte Park, 1955. Oil on canvas, 48 x 36 inches. Estate of the artist, Courtesy Spanierman Modern, NY.

.

Park's techniques included combining the use of brushes with palette knives, and one sees a lot of areas where paint has been scraped onto and off the canvases, as can be seen in Zachary, c.1955.

.

"Zachary" by Charlotte Park, 1955. Oil on canvas, 36 x 47 inches. Private collection, Pittsburg, PA.

.

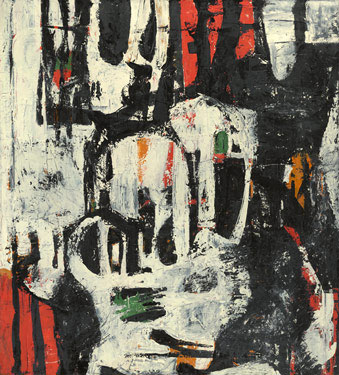

There are several black and white works in this exhibition as well, a mode that a lot of the artists of the time liked to work in. Eschewing the power of color allowed them to rely more completely on composition, which was such a major element in the dynamics of painting then. Untitled, Black and Gray and Untitled, Black and White are strong examples of this approach.

.

"Untitled, Black and Gray" by Charlotte Park, 1950s. Gouache on paper, 8 3/4 x 14 inches. Estate of the artist, courtesy Spanierman Modern, NY.

.

Park’s works from the ‘50s show a prowess in composition, whether done in color or black and white. She used all the various devices common to the genre, like automatic writing, push/pull, and accident, but she was never content to let any of these decide the final outcome. Rather, she used these techniques to start her works, but eventually her desire to create balance and tension determined how the paintings would be completed. In this she shared the approach to spontaneity and chance with her husband, James Brooks, who once said he wanted to "absorb the accident."

If any single driving force could be said to inform Park’s approach to painting, it would be the urge to contain opposites. This can be seen in her compositions, her colors, and in the process she used in creating her work. There is both spontaneity and deliberation in her development of forms that represent nature and empiricism with forms that appear through gesture.

.

"Lament" by Charlotte Park, 1955. Oil on canvas, 40 x 36¼ inches. Estate of the artist, courtesy Spanierman Modern, NY.

.

The fact that Park is apparently now being "discovered" raises questions as to why it did not happen before. It is certainly a given that the bias in the ’50s completely and utterly favored the men. And while there is no doubt about that, it falls short of providing the whole picture.

Both Park and Brooks were basically introverted people, with Jim even a bit more so than Charlotte. It took great effort on his part to go out and socialize "with the boys" and stay in the scene, which was, even then, absolutely necessary to maintaining a career. Both Brooks and Park were very light drinkers; they would never even approach the level of functional alcoholics achieved by so many of their friends. And it was against both of their natures to self-promote.

So, being as sober and demure as they were, they found themselves having to paddle upstream within their peer group. Since this was a hard row to hoe, it was clear that it would take a huge effort just to keep Jim's career alive. Charlotte knew how things were slanted, and that only he really had a chance at that point in time, so she put her weight behind him so they both could survive as artists. Unfortunately, there really was no better choice at the time.

Thanks to the joint effort, they did succeed and managed to live comfortably off the sales of his work for the last 50 years of their lives. Charlotte actually reveled in this and in her support of her husband, and had no envy or bitterness, another indication of her great character and dignity. Her husband’s success allowed them both to paint and live the way they wanted to live, unencumbered by having to hold steady jobs. Occasional teaching was the only ancillary work they performed; she taught art at MoMA and was a favorite of the many artists' kids who took her classes there.

I once asked Park how she felt about the feminist movement in art and some of the prominent women near her generation who had first championed it, like Mimi Shapiro, whom she knew quite well. Park said, "I don't want to be known as a female artist. I want to be known as a good artist." She had no interest in playing the gender card. Her dear friend and another under-recognized artist, Cile Lord, confirmed to me that Lee Krasner "said the exact same thing."

It's important to remember that those whom Park respected most—couples like Pollock and Krasner, the Marca-Rellis, Cavallons, deKoonings, Lassaws, Nivolas, Gottliebs, Vicentes, Lords and Parkers, and individuals like George McNeil, Franz Kline, Phil Guston, Marc Rothko, Robert Motherwell and Alfonso Ossorio, along with writers like Stanley Kunitz and critics Harold Rosenberg, Thomas Hess and Irving Sandler—had acknowledged her work, if only privately. An artist who has that kind of camaraderie and support can never really feel completely ignored. And while she might have enjoyed having more recognition, she never seemed in the least affected by not having a more public fame.

Park once told me that in the early days when artists of the modern era had settled in to work on the East End, they used to visit each other’s studios in the afternoons "just to see if it was really okay to be doing what we were doing!" That's how fresh and strange it was for them, this pursuit of something as new as Abstract Expressionism was at that time. She clearly had a very full and rewarding artistic life and she produced consistently and uncompromisingly for 50 years.

For Charlotte Park, that's what mattered most.

_________________

BASIC FACTS: “Charlotte Park:The 1950s” remains on view through Oct. 31, 2013 at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center.

They are open by appointment only on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays. Reservations are required and can be made by calling 631-324-4929. The exhibition can be viewed as part of a one-hour tour. Admission is $10 for Adults (age 12 and over), $5 for children (accompanied by an adult) and free for infants.

The Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center is located at 830 Springs Fireplace Road, East Hampton, NY 11937. 631-324-4929; www.stonybrook.edu/pkhouse

_________________

Copyright 2013 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.

Wow, this is so exciting, stimulating aesthetically to read these in depth articulate and outstanding reviews by–so far — Eric E. and Mike Solomon! made my day so far, and yanked upward my mediocre thinking / articulation about art.

I had the surprise and exceptional good luck back in early 80’s to have dropped in at a major 57th St gallery in nyc to see James Brooks ‘ show. It was overwhelming — the large powerful paintings, and most of the crowd had left. For some strange reason, both of them joined me In a quiet corner to talk art!!

That was my first and only meeting with C, Park and her husband–Indeed gentle lovely thoughtful people…how fortunate I had that opportunity and memory still.