Assigning works of art to different categories—abstraction, figuration, expressionism—is too often done without a complete understanding of what fragile constructs they really are.

Jackson Pollock believed that his splatter paintings—springing from the muscular actions of his body over the canvas—were not abstractions, but actually figurative works. “I’m very representational some of the time,” he said, “and a little all of the time.”

Jean Dubuffet wrote: “There is no such thing as abstract art, or else all art is abstract, which amounts to the same thing.”

Alfonso Ossorio said of abstraction: “You have to have something to abstract.”

All three of these artists, whose work often bled back and forth across the borders of representation and abstract layering, had a rich, ongoing dialogue in both letters and art. This intriguing interchange is now being examined in a show of some 50 paintings and works on paper in “Angels, Demons, and Savages: Pollock, Ossorio, Dubuffet,” on view through Oct. 27 at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill.

Central to the trio was Alfonso Ossorio. A wealthy, Filipino, Catholic, openly gay man, Ossorio was also both a collector and an artist. He was the conduit, befriending first Jackson Pollock and then at Pollock’s suggestion, the French artist Jean Dubuffet. And though Pollock and Dubuffet never actually met, they did correspond. Through letters, through their friendship with Ossorio, and through a familiarity with each other’s work, they shared a strong mutual exchange of ideas and techniques. Paramount for all three artists was the strong “itch” to experiment with various techniques, as well as a shared consideration of the figure as interwoven into the textured background of a painting.

Though born in the Philippines, Ossorio was educated in England and the United States. After becoming a painter, he was introduced to Pollock by the art dealer Betty Parsons. By the late 1940s, Ossorio had begun acquiring many drip paintings by Pollock and, at Pollock’s suggestion, Ossorio visited Dubuffet on a trip to Paris in 1949. A year later, in 1950, Ossorio returned to the Philippines to paint a mural for the chapel of St. Joseph the Worker on the island of Negros Occidental, while Pollock and Lee Krasner stayed in his New York house.

It was during his time in the Philippines that Ossorio began experimenting with a wax-resist technique on small drawings done on torn pieces of Tiffany & Co. stationery. These are the luminous Victorias Drawings, named for the site of the chapel within the Victorias Milling Company compound in Victorias City. Corresponding with Dubuffet, Ossorio included many photographs of these brilliantly colored works in his letters. These images later inspired Dubuffet to write an essay on the work of Alfonso Ossorio, “The Initiatory Paintings of Alfonso Ossorio,” in 1951.

Dubuffet had a rebellious approach to art. He was inspired by graffiti and the so-called “outsider” art of psychiatric patients, prisoners and children, work that was at odds with the academic, classical notions of beauty in art. Coining a new term, “Art Brut,” for this more raw approach, he used found materials, from twigs and sponges to butterfly wings and dirt, in his art and saw the body, particularly the female body, as landscape. In Terracotta la grosse bouche (Big-mouth terracotta) 1946, and the later Corps de dame jaspé (Marbleized Body of a Lady), 1950, the huge naked women are gritty, scratched out of the sand surface of the canvas. They are terrestrial beings, creatures shaped out of the melding of the raw materials surrounding them.

.

"Corps de dame jaspé (Marbleized Body of a Lady)" by Jean Dubuffet, 1950. Oil and sand on canvas, 39 ¾ x 29 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., The Stephen Hahn Family Collection, 1995.29.8. 2013 © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

.

By the early ’50s, Pollock, too, had moved away from the canvas as a repository for action and was creating strong black and white images that are clearly representational. In the large enamel and oil on canvas, Number 7, 1952, one can see not only a head, but also Pollock’s own footprint in the upper right corner, and the exhibition catalogue points out that Pollock’s re-engagement with more overtly figurative work may have been due in part to his time staying at Ossorio’s home.

.

"Number 7" by Jackson Pollock, 1952, 1952. Enamel and oil on canvas, 53 ⅛ x 40 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, Emilio Azcarraga Gift, in honor of William S. Lieberman, 1987. 2013 © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

.

In 1951, at Pollock’s urging, Ossorio purchased the Creeks, a 60-acre estate on Georgica Pond in East Hampton, NY. And it was there that Ossorio housed not only his growing collection of art that included both Pollocks and Dubuffets, but also Dubuffet’s own collection of Art Brut (Raw Art). The Creeks and the notoriety the estate engendered turned out to be a mixed blessing, as Ossorio’s hospitality, his wealth, his status and generosity as an art collector have for too long overshadowed his talent as an artist. And it is his paintings that are the real surprise of the show.

Ossorio was an artist’s artist. His work displays a unique gift for overlapping water-based pigments with layers of wax and black ink, creating densely colored yet transparent surfaces out of which forms and figures rise.

In Full Mother, 1951, a large oil and enamel on canvas, both the influences of Pollock’s scratchy lines and drips of paint and Dubuffet’s overpowering full-frontal forms are apparent. Yet Ossorio has his own iconography: the woman with her feet together and her arms spread wide is clearly also a Christ-like figure.

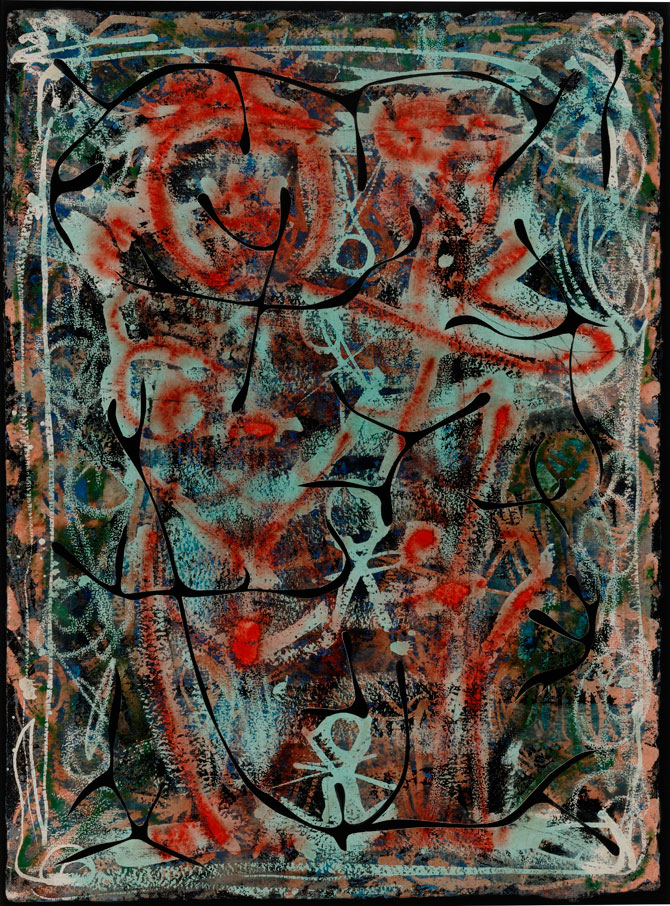

That same year, on black paper, Ossorio painted Couple and Progeny. Here the red figures of the couple and the delineated dark lines of the background surface meld with the swirl of dripped wax and the intricate field of markings of ink and watercolor.

.

“Couple and Progeny” by Alfonso Ossorio, 1951. Ink, wax, watercolor, and cut paper mounted on black paper, 30 x 22 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y. Gift of Edward F. Dragon. Courtesy Parrish Art Museum.

.

But it is in the later painting, Reforming Figure, 1952, that Ossorio seems to have merged the inspirations of Pollock and Dubuffet to create his own metaphysics. In this painting, the figure and the wax background seem to be creating each other. Neither has authority; both are interdependent and simultaneous.

In writing about the work of his friend, Dubuffet said that Ossorio “wed shapes and colors so closely to those of the composite milieu surrounding them that they seem to have no substance of their own—no other substance but this cosmic soup in which they swirl and surge.”

.

"Reforming Figure" by Alfonso Ossorio, 1952. Ink, wax, and watercolor on paper, 60 x 38 inches. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Gift of the Ossorio Foundation, 2008.

.

All three of these artists were concerned with examining the chaos out of which form was born. In Dubuffet’s Paysage metapsychique, done a year after he wrote about Ossorio’s “composite milieu” and “cosmic soup,” Dubuffet painted a rubble-strewn landscape that seems to take up most of the canvas. As dense as any of Ossorio’s work, it is only at the top of the painting that we see vaguely organic shapes that seem to be sprouting out of the soil of the canvas.

.

"Paysage métapsychique (Metapsychical Landscape)" by Jean Dubuffet, 1952. Oil on canvas, 51 ⅛ x 63 ¾ inches. Des Moines Art Center, Gift of Melva Bucksbaum in honor of the Des Moines Art Center’s 50th Anniversary. 2013 © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

.

The Parrish show also includes one of Dubuffet’s great “texturologies” from the mid ’50s: a painting that, like Pollock’s drip paintings from a few years earlier, appears to be completely abstract. In fact, it is anything but; it’s a landscape of light and matter, as if the earth itself had been placed under a microscope and brought into high relief.

“Angels, Demons, and Savages” is a unique exploration of the cross-cultural exchange facilitated by the angelic Ossorio between Pollock, an artist haunted by demons, and the “savage” Dubuffet. It readdresses the Clement Greenberg fallacy that the history of 20th century art followed just one mainstream: from representation to pure abstraction. What is true is that constructs in art are often arbitrary and the artists who work in the murky, shape-shifting landscape between poles are too often sidelined because they don’t fit into easy categorization.

Certainly, this is true of the work of Ossorio, with Dubuffet calling his friend’s paintings “incorporeal abstractions.” The same could be said of both Dubuffet and Pollock. The work of all three painters inhabits a place where oppositions and the tensions between them meet to form another meaning.

BASIC FACTS: “Angels, Demons, and Savages: Pollock, Ossorio, Dubuffet” remains on view through Oct. 27 at the Parrish Art Museum, 279 Montauk Highway Water Mill, NY 11976. www.parrishart.org.

Alfonso Ossorio's work is the subject of an upcoming solo show at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in New York City. "Alfonso Ossorio: Blood Lines, 1949 - 1953" will be exhibited from Sept. 7 to Oct. 27.

RELATED: "Angels, Demons, and Savages: Pollock, Ossorio, Dubuffet" Explores the Cross-Cultural Dialogue"

________________________________________

© 2013 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. All rights reserved.