“Drawing Surrealism” at the Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

“Drawing Surrealism,” co-organized by the Morgan Library & Museum in New York and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, clearly demonstrates why no other art movement of the modern era is as ubiquitous as Surrealism. Almost 100 years out from its inception, Surrealism has either overtly or insidiously infiltrated every subsequent art movement and medium of expression, and its techniques have become a basic part of the lexicography of art.

"Cadavre exquis" by André Breton, Jacqueline Lamba, Yves Tanguy, 1938. Collage. 16 1/2 x 12 1/4 inches. Gale and Ira Drukier. Courtesy The Morgan Library & Museum.

Though all art could be said to have psychological underpinnings, Surrealism was the first movement that deliberately and consciously occupied itself with the psychological, in large part because of the revolutions in the human sciences that were happening at the time.

The influence of Sigmund Freud, whose ideas and career were in full bloom at the birth of the movement, was a major factor, and Surrealism’s founding theorist, André Breton, had a strong background in psychology. He, along with other influential writers and artists like Guillaume Apollinaire, Georges Bataille, André Masson and Joan Miró, became interested in employing processes for art making that were developing in psychiatry to bring out the workings and visions of the psyche, like the Rorschach test. As Alberto Giacometti said, the idea was to “represent the unrepresentable.”

This exhibition focuses on the techniques the Surrealists used to achieve that goal and specifically on drawings. While some of their techniques came from psychology, others, like collage and photomontage, came from Surrealism’s slightly older cousin, Dadaism.

The exhibition is conveniently organized by Surrealism’s procedures. Automatic Drawing, Collage, Frottage, Decalcomania, Exquisite Corpse, and Dream Imagery are the categories that structure the show and its flow in the stately galleries of the Morgan Library, and the examples in each group are superb.

From the first work by Apollinaire, his so-called calligram Mandolin, Carnation and Bamboo, c. 1915-17, a work in which words and verses were graphically constructed to create images, to Ellsworth Kelly’s Brushstrokes Cut into Forty-Nine Squares and Arranged by Chance, 1951, the show is thorough in providing the chronology, range and influence of Surrealist practices.

Exhibitions like these, which aspire to be definitive, will always be vulnerable to criticisms of what was not included. And so it should be noted that here, even given the limitations inherent in organizing such a comprehensive cataloguing of a complex movement, it would have made sense to include works by Valentine Hugo, Dora Maar, Méret Oppenheim, Dorothea Tanning, David Hare, Remedios Varo and Charles Seliger. Nevertheless, their omission does not significantly devalue the show in any major way.

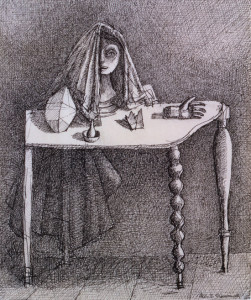

"La table surrealiste (The Surrealist Table)" by Alberto Giacometti, 1933. Ink on paper, 16 7/8 x 15 inches. Collection Michael and Judy Steinhardt, New York. Courtesy Morgan Library & Museum.

One of the notable things about Surrealism is how nationally diverse it was. The exhibition includes contributions from Surrealist groups in Great Britain, Spain, Czechoslovakia, Serbia, Mexico, the U.S., and Japan. The examples of works by women are very significant too—if not in the same numbers as men, then certainly in quality. As the premise of Surrealism was to delve into the psyche, the experience of gender was a major and integral theoretical component and so the involvement of women was absolutely crucial in establishing its claim to universal validity.

The show includes works by Eileen Agar, (Ladybird, 1936, is incredible!) Louise Bourgeois, Leonora Carrington, Frida Kahlo, Jacqueline Lamba, Grace Pailthorpe, Edith Rimmington (check out the Hobo art frame on the work Family Tree) Kay Sage and Toyen (Marie Čermínová).

The exhibition also includes seminal object/documents, like Breton’s “Les pas perdus,” a collection of essays Breton wrote between 1918 and 1923, the years leading up to the formation of Surrealism and “Le message automatique” published in Minotaure in 1933, in which he claims that parapsychology was an antecedent to the Surrealists’ exploration of the unconscious. The article is illustrated with drawings by “Mediums” that Breton found in the Annales des sciences psychiques from 1908 to 1910. There is also a copy of VVV, the Surrealist publication produced in New York during WW II by some of the expatriated group, who spent time both there and in the Hamptons during the war years at the invitation of Peggy Guggenheim.

Most importantly, by focusing on the process of drawing, rather than the more involved and planned activity of painting, the exhibition gets right to the essentials of the movement. Though most of the artists included produced paintings, working on paper was the core practice of Surrealism.

Drawing’s ease allowed the artists to be comfortable in taking the risks necessary to uncover the recessed aspects of internal experiences. In the 1920s, Surrealist art was unprecedented in its unveiling of psychologically based visualizations. The Surrealists had been inspired in turn by seeing the art of the insane that had been collected and written about by Dr. Hans Prinzhorn at the University of Heidelberg in 1922.

Now, of course, in the age of digital media, so much of what we do is re-contextualizing visual images. The term “cut and paste” though known today as the most common denominator in the plethora of graphic tools available in software like Photoshop, was originally and literally the act of manually cutting and pasting photos and other elements in collages and photomontages.

"La tempete (The Storm)" by René Magritte, 1927. Graphite pencil, 7 3/8 x 9 3/8 inches. Private collection. Courtesy The Morgan Library & Museum.

The Dadaists first borrowed collage from the Cubists and used it to serve as a “low” material in protest against the “high” status of the more expensive oil painting that represented bourgeois society in Germany and other parts of Europe.

While Dadaism used collage as a political critique meant to shock conservatives, Surrealism’s concerns were of a different nature: its interest was in the human condition itself and so the juxtaposition of images made through cut and paste was directed towards imitating the psychological processes that take place in the mind, like dreaming, when subjects from daily life are picked up and moved and remixed by the psyche to form a new narrative. It is perhaps this single aspect of Surrealism, striking such a major vein of human experience, which gave it such staying power as a movement.

The other major achievement that came out of Surrealist juxtaposition was the invention of the visual metaphor. We see this so clearly in Rene Magritte’s 1927 drawing “La Tempete,” in which a man in a hat and overcoat shields himself from a storm of … cutlery. I doubt that there are many instances in art prior to this drawing in which images of disparate objects are joined to make such an exact literary analogy. It’s no surprise that this was done by the artist who used words and images as equal elements in fine art for the first time, who said, “in a picture, words are the same substances as images.” Magritte opened the door for all who’ve worked with words ever since, artists like Ed Ruscha, Barbara Kruger, Richard Prince and countless others.

Another example of a visual metaphor is the 1940 work by Jindřich Štyrský, “Le reve de poisson.” The image shows a fish with human legs extending from its underbelly in place of fins. It is curious how often animals are depicted in Surrealist works. Perhaps the animal archetype suffuses a creational content that supports Surrealism’s scouring of the deepest recesses of the imagery of our memory. Animals are presented out of context too, by being set in odd locations. This mode could be said to be the foundation for contemporary artists like Michael Combs (see his work, “The Wish,” 2008) and for the recent wonderful and very surreal movie, “Life of Pi.”

There’s tons of evidence all around us of Surrealism’s Big Bang influence. Surrealism was, is, and will be a genre to contend with for as long as we seek to try to represent that which goes on within. This extremely interesting and well organized exhibition on the movement’s origins shows us myriad reasons why Surrealism lives.

Mike Solomon

______________________________________

BASIC FACTS: “Drawing Surrealism” is exhibited from Jan 25 to April 21, 2013 at the Morgan Library & Museum, 225 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016.

RELATED STORIES: Surrealism Explored through its Drawings by Pat Rogers. Published Jan 24, 2013.

ART REVIEWS BY MIKE SOLOMON:

"Matthew Satz, Considered." Published March 14, 2013.

"No Slouch!’: The Spray Lacquer- Metal Flake Paintings of John Chamberlain." Published March 3, 2013.

_______________________________________

Want to know what’s happening in the Hamptons art community? How about the North Fork or NYC? Visit HamptonsArtHub.com to find out.

There’s plenty of art news, art fair coverage and artists with a Hamptons / North Fork connection.

Hamptons Art Hub. Art Unrestricted.

________________________________________

© 2013 Hamptons Art Hub LLC. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. This includes all photographs and images. Text excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to HamptonsArtHub.com and the author with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.